Cliff Eyland

Cliff Eyland has loved libraries since he was a kid, reading his way through his local branch in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. The long-time Winnipeg-based artist has spent decades reconciling what are sometimes seen as the opposing cultural claims of libraries and art galleries. “Five Hundred and One Paintings + Buildings,” a recent show of new work at Winnipeg’s Actual Gallery, explores the cerebral and the tactile with multiple small pieces including a long line of “Book Paintings,” which are stylized covers of imagined antiquarian texts, and a cluster of vivid, wildly eccentric images of “Librarians and Patrons.”

Since 1981, the 61-year-old Eyland has worked in a 3 x 5-inch format, obsessively producing thousands of small paintings on small Masonite panels, as well as drawings and notes. The dimensions of these works reference the index cards once used in library card-catalogues. These cards are now quaint artifacts, and libraries have become contested, often endangered spaces. In a way that Eyland couldn’t have anticipated back in the ’80s, his ongoing artistic investigation into institutional information systems has overlapped with a massive technological, social and cultural shift from book-bound learning to decentred digital data.

Cliff Eyland, Book Painting, 2014, medium-density fibreboard, 3 x 5 inches. Photographs: William Eakin. All images courtesy Actual Contemporary, Winnipeg.

Eyland has hidden 3 x 5 drawings in books at The New School’s Raymond Fogelman Social Sciences and Humanities Library in New York, the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and the National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives in Ottawa, among other places, along with unofficial interventions elsewhere. In the last decade, Eyland has also become known for large-scale site-specific installations for Canadian public libraries, including a wall made up of 1,000 small paintings for Winnipeg’s Millennium Library in 2005. In 2014, he created a 600-piece work at the Meadows library in Edmonton, along with an astonishing 5000-plus install at the Halifax Central Library.

As these projects suggest, Eyland’s endless intellectual curiosity has been channelled into an artistic bibliophilia that recognizes the book not only as a repository of ideas but also as an object, with its own look, feel, even smell. Eyland’s work celebrates the eroticism of ideas, challenging cultural stereotypes of libraries as hushed, sterile centres of controlled and regulated information. In Eyland’s view, libraries are places of chaos and entropy, home to sudden, idiosyncratic urges, quirks of taste and all kinds of fertile and promiscuous knowledge-swapping. His series of “Librarians and Patrons” reflects that vision, offering not literal portraits but a sense of strange, teeming, organic vitality. Some of the images possess the frazzly energy of Automatiste scribbling, others the concise comic line of caricature. There are human faces and figures, but also hybrid monsters and febrile plants. Many of the works are painted in pop candy colours so that taken as a whole, the collection hangs between delicious and just a bit queasy.

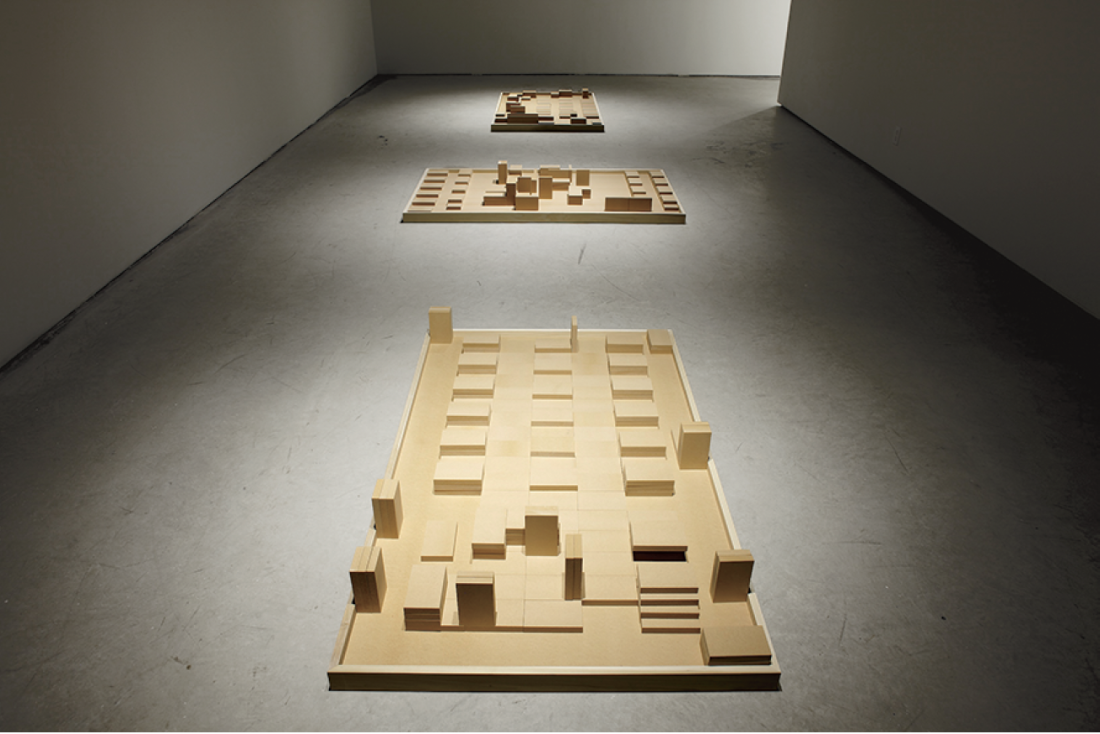

Installation view, “Five Hundred and One Paintings + Buildings,” 2015, Actual Contemporary.

The “Book Paintings” section of the show is about books, of course, but also about art history. The images are organized in one long line. At a distance, they resemble a collection of 18th- and 19th-century texts, but Eyland riffs on the look of marbleized endpapers in a way that suggests trippy biomorphic abstraction. There’s also a nod to hard-edged abstraction with the vertical stripe of colour that stands as each volume’s binding. While the format is reductionist, there are, here and there, suggestions of mildew and must, dust and age, signifiers of specific books and their promise of imagined worlds.

The Actual exhibition also includes a series of “Sculptures in Landscape,” sometimes poignant, frequently comic collisions of culture and nature. Here, the 3 x 5panels are oriented horizontally, most of them depicting abstract public sculptures somehow stranded among scrubby Group of Seven pines or rusting out on starkly beautiful stretches of prairie. The “Buildings” section of the show consists of sculptural architectural models, placed on the floor and built up with buff-coloured MDF blocks, again in the prescribed 3 x 5-inch format. The standardized blocks suggest the modular foundations of International Style Modernism, though the exact nature and purpose of the structures remains enigmatic. They could represent a convention centre or prison bunkers or some Utopian dream.

Buildings, 2014, medium-density fibreboard, 3 x 5 inches.

A show of 501 pieces (plus buildings) could seem prodigal, even reckless, but with Eyland it just feels generous. His artistic output is prodigious, even by the standards of his fellow Winnipeg artists, whom he calls “cabin-fever eccentrics,” men and women who while away long winters in art-making. He has also worked as a curator, archivist, teacher and writer, seeing these activities as extensions of his artistic practice.

Eyland’s bookish work embodies his even-handed but obsessive devotion to both idea and object. He always works within the stringent 3 x 5-inch format, the images produced in a serial process with strict uniformity. Within this rule-based system, however, he pulls off a crazy, messy, funny exuberance.

Almost every individual work is a lovely little thing, something about the small size luring us in. The 3 x 5 proportions reference both the classical golden mean and the postmodern pleasures of a well-designed smartphone, which again make us want to hold and handle these pieces. They have a particular physical presence, and Eyland’s continued commitment to old-school drawing and painting fits into the lo-fi, DIY ethos that has been a persistent presence on the Winnipeg art scene.

Installation view, “Librarians and Patrons” and “Book Paintings” series, from “Five Hundred and One Paintings + Buildings,” 2015, Actual Contemporary.

At the same time, when Eyland’s works are arranged collectively, exhibited in lines and grids, they function as investigations into systematized information. Seen from a distance, these patterns can resemble digital pixels or the kind of repetitive visual data seen on social media platforms like Instagram or Pinterest. The overall organization of the Actual exhibit suggests this other side of Eyland’s approach, which traces back to his training at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in the 1980s, when the school’s well-known Conceptualism was still holding on.

In “Five Hundred and One Paintings + Buildings,” Eyland packs his serious framework with playful particulars, creating art that is both brainy and sensuous. Simultaneously looking back and looking forward, his work suggests the complicated possibilities of our current information age. ❚

“Five Hundred and One Paintings + Buildings: Recent Work by Cliff Eyland” was exhibited at Actual Gallery, Winnipeg, from December 30, 2014 to March 21, 2015.

Alison Gillmor is the pop culture columnist for the Winnipeg Free Press and writes regularly on visual arts and film.