Claude Tousignant

“3 Paintings. 1 Sculpture. 3 Spaces” spoke with refreshing eloquence to the crossroads at which constructive Abstraction finds itself in mid-2005—the juncture where painting and architecture meet. It was also an epiphany for those of us who have followed Montrealbased abstractionist Claude Tousignant’s long pilgrimage over the years. This stalwart late Modernist shows no signs whatsoever of slowing down. The monumental one-and two-colour constructions he exhibited at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery were a meditative immersion in monochromism. They brought home to us not only the implacable logic of his whole démarche, but its lush, chromatic life as well. The works did not ask that we humble ourselves; they did, however, demand measured reflection over time.

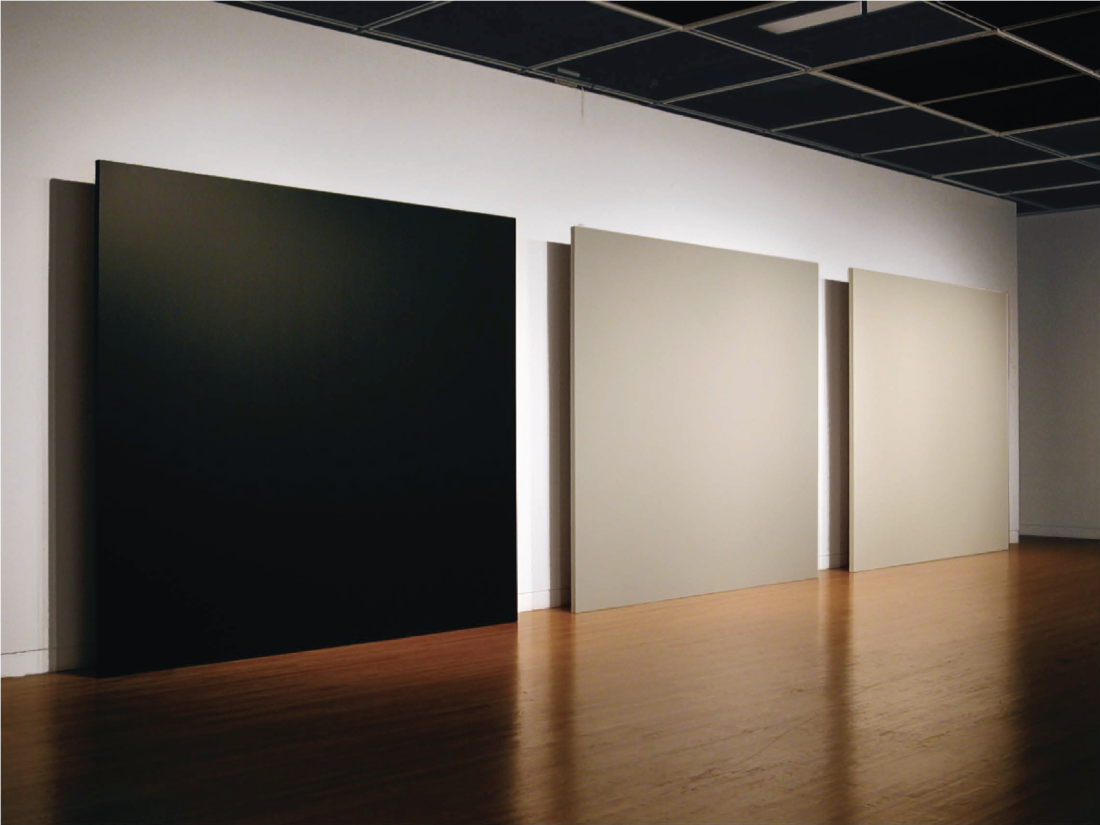

Immediately inside the gallery, three, massive, monochrome panels staked an irrevocable claim upon us. This triptych, titled Codicille, 2002-2003, formed of adjacent black, grey and white canvasses (each measuring 284.5 cm by 314.9 cm) was meant to be read from left to right. The work was powerfully moving. The title was also food for thought: codicil, a supplement to a will; a testamentary instrument intended to alter an already executed will. Tousignant has never forsaken his belief in claiming “object” status for painting, and in this exhibition, he seemed to up the ante from discrete object or even environmental artefact to environmental volume and lived architecture.

As I paced the width of the three monochromes, I recognized, and not for the first time, the painter’s signature use of colour to express space, and space to express colour. He invests colour with a thick dimensionality of depth and distends its presence into our lived space. It’s impossible not to reflect on the remarkable fact that, for 50 straight years of abstract practice, he has sought to empty painting of all referents to things outside itself in order to achieve full autonomy, or, as he would aver, full dignity for it among all other objects in the world. The same old question presents itself: after methodologically subtracting all the referents, all the enervating and perhaps necessary echoes to a world outside, what is left? What is left for us to experience in these humungous black, grey and white fields—magnetic void, vault of heaven, sheer wealth of impossibly saturated, sensuous, seductive, skin-like chroma?

Claude Tousignant, Modulateur de lumiere, 2005, acrylic on aluminum, 284.5 x 213.3 x 203.2 cm installed, 4 elements, each 284.5 x 121.9 cm. Photographs courtesy Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery, Montreal.

Carrés blancs, 2005, is a vast white painting with a smaller, diaphanous, blue square set right in the middle, a perfect square of some otherwordly pollen or a silken handkerchief that had somehow been carefully laid down on the white surface. Carrés noir et gris, 2004, had a similar impact, with the black square as mysterious and austere as the blue was diaphanous and uplifting. Codicille’s three, vast monochromes rested on the floor and extruded on steel struts some 12 inches from the wall. I thought peripatetically of bipartite graphs, the colours of earth chakras and the genetics of piebald cats. But here was a progression through chromatic simplicity that became, at a certain moment, overwhelmingly complex. While the uniform size and extrusion from the wall plane seemed to equalize the monochromes’ weight and presence in the world, the truth is that the black square seemed to recede into the wall or exert a magnetic pull, always inwards. This quantum of black paint had a decidedly recessive quality.

The grey zone seemed like an interpolation, neither receding nor advancing. Here was an intermediate and transitional stage of the horizonal/horizontal array, a rest for the eye. Then the white monochrome seemed impossibly more frontal, so the lateral movement along the flanks of the paintings also became a matter of being pulled in and pushed out by the monoterms as though they were architectural facades at different orders of depth, staking differing claims upon the body, optic and embodied imagination of the observer. In other words, it was simply impractical to complete looking at the painting without its becoming a contradiction, and remain a passive spectator.

The black panel was the cave gateway to nowhere in Mantegnas Descent of Christ into Limbo, the black maw threatening to swallow us whole. Looking, I trembled on the very brink of a wholly abstract space, but after a time came to register, like Narcissus, my own reflection staring back out from that terrifying dark mirror.

Some years ago, I likened Tousignant’s Sculpture of 1974-77 to a Gustave Courbet canvas of 1864, La Source de la Laue, and I think the family resemblance still holds true. In the region of France where Courbet grew up, there is a huge cave from which the Laue River flows. The unknown source of the river is somewhere deep underground. The painter assumed a perspective with his brush at the very lip of the cave, so vertiginous a standpoint that we feel we are being drawn down into that vast sea of black. There is a phenomenal solidity to the mass and texture of the oil paint itself that signals the triumph of pigment as material, much the same materiality that pigment enjoys in Tousignant’s monochromes. While it may seem a stretch to compare a Tousignant monochrome to a Courbet painting executed almost a century and a half ago, the truth is that they have much in common. They share a fierce belief in the reality of the painting as an object in itself; both surface and paint self-present. For Courbet, paint and canvas assumed a status as core subject matter achieving parity with the represented.

Claude Tousignant, Codicille, 2002-03, triptych, each panel 284.5 x 314.9 cm.

The curved space in Tousignant’s Arches work of the 1970s—or the black monochrome in the current exhibition—is remarkably close to Courbets representation of the arch-like opening into an unfathomable subterranean space. The semiotic wealth of both paintings is simply vast and borders on “the Sublime.” We are embedded in a space that seems at once two-dimensional and absolutely bottomless. The mise en abîme of our doubled representation inside the field is ensured through the tripling of the monoterms, holding us taut between a moment of dissolution and a moment of pure immanence. Was it Courbet, and not Mondrian, who is the true source of Tousignants underground reveries, his monochrome fascination? Well, it is impossible for us to say with any real certainty.

However, we can state with certainty that colour here has as much to do with time and space as it is does with our emotions, somatic vicissitudes and imaginal propensities. Colour here really is space. Tousignant’s paintings (or, rather, his sculptures, since he insists on calling his work from 1981 “sculpture” or “picto-sculpture”) are characterized by simple forms that “essentiate” colour-terms. When we study a given work, we read the colours that he essentiates there for us as primary semantic data.

Tousignant has attempted, with varying degrees of success, to break the back of traditional pictorial space and transplant a new vertebra in the space of a living object. He wants a primal domain that is expressly constituted by dynamic, chromatic planar surfaces that operate on our bodies, our handedness, our eyes and our minds, and that imparts something new and strange to our own experience. This is certainly true of the stand-alone sculpture in the exhibition, Modulateur du Lumiere, 2005. In this work, four, vertical, extended, V-shaped elements, each measuring 284.5 cm high by 121.9 cm wide, are positioned in such a way that there is a narrow vertical alcove we can enter. Inside, where the light enters in between the elements, opaque, white-painted aluminum has lost all materiality and has become as delicate and translucent as Japanese rice paper.

I suspect that for many visitors to the Tousignant exhibition, monochrome will remain as enduring a mystery as the source of the Loue, and as mysterious as the mouth of the cave from which the river water springs. But mysteries are sustenance on life’s journey. I have long felt that Claude Tousignant deserves something like the situation Rothko has at the Houston Chapel in Texas. Whether he achieves it depends on our willingness to recognize the integrity, achievement and continuing promise of an abstract practice that, 50 years on, shows no evidence of winding down. ■

“3 Paintings. 1 Sculpture. 3 Spaces. Claude Tousignant. Black. Grey. White.” will be on exhibit at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery, Montreal, from May 26 to July 9,2005.

James D. Campbell is an independent curator and writer based in Montreal. His latest book is Nightland: The Art of Dana Velan (2005), co-published by the Maison de la Culture Frontenac, Montreal, and Spin Gallery, Toronto.