Claude Tousignant

The expansive retrospective of Claude Tousignant at Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal celebrates his 50-year career and significant contribution to the practice of abstraction in particular and to Canadian painting as a whole. Curators Paulette Gagnon and Mark Lanctôt organized the exhibition in chronological order— from early experiments with mark making and material processes to recent sculptural work exploring spare and architectural forms. The show maps Tousignant’s journey towards developing his unique non-representational language. Presenting his best-known as well as exploratory works, this exhibition offers an opportunity to understand what continues to motivate this artist and inspire his prolific career.

Entering the exhibition, viewers encounter Tousignant’s earliest abstract paintings executed with an all-over technique covering the surfaces in pure colours as though straight from the tube. The thirteen “Tachist” paintings, 1954 to 1956, are small-scale works in which Tousignant uses slight marks, literally dabbing at the supports with his brush. Within these paintings, the brush strokes create organic looking forms in a variety of widths, lengths and arrangements—unlike the hardedge approach for which he is known. Les Taches, 1955, is one of the most resolved works in this series. Painted on a white ground, brightly coloured taches in orange, red and yellow are intermingled with dark brown and black sprinkled liberally across the canvas.

Claude Tousignant, Les Taches, 1955, oil on canvas, 43.7 x 56.7 cm. Collection of the artist. Photo: Guy L’Heureux. Courtesy Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

Collectively, these early works suggest the artist was searching for something—perhaps a visual language that suited his personal pursuit of abstract form and that opposed the landscape spaces of his Montréal predecessors, Les Automatistes. In formulating his strategy, Tousignant developed an interest in the relationships created between the taches, signalling his future concerns regarding conceptual relationships among elements. Exploring how marks, forms, lines and colours function in relation to one another would drive his subsequent projects.

Within the gallery devoted to 1950s works, a more intimate installation features the famous Galerie L’Actuelle works from 1956. Tousignant’s painting takes a dramatic-yet-crucial turn here towards hard-edge abstraction. Structurally simplified, saturated colours are used and any background/ foreground relationship is eliminated. Larger in scale than previous work, these paintings, constructed with vertical or horizontal planes, were experiments with medium as well as form. Because acrylic paint was unavailable in Montréal until 1958, some artists tested mediums that were often unstable and fragile. Tousignant employed car paints and leather dyes to achieve his abstract goals. Many of these paintings were damaged because the paint did not properly affix to the supports. Undaunted, Tousignant simply re-made them in 1969, believing that the original is subordinate to the approach and the painting is therefore an object of secondary importance. He used car enamel on canvas for Les Affirmations, 1956, and it was not re-made. Despite its chipped edges and finely cracked surface, this work shows Tousignant allowing colour to serve an energetic and relational function. The purity of the design and equally distributed quantity of colour over three horizontal bands achieves a dynamism and affirms the two dimensional nature of the surface, reinforcing its flatness.

Claude Tousignant, Hommage à Barnett Newman, 1967–1968, acrylic on wood and plywood, 274.5 x 488 x 228.5 cm. Collection of the artist. Photo: Guy L’Heureux. Courtesy Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

Evidence of Tousignant’s growing interest in relationships between formal elements and concern for an equal distribution of colour characterized his next major body of work. The 1960s gallery was filled with bold colours systematically organized in circular form; together, the “Chromatic Transformers,” “Gongs” and “Chromatic Accelerators” provide a comprehensive experience for the senses. The gallery installation demonstrates Tousignant’s development— from using concentric circular forms within a square or rectangular canvas to eventually breaking free of the constraints posed by the right angle by marrying form to format with circular-shaped canvas. He also multiplied the number of concentric rings within each canvas and complicated the colour organizations by creating non-repetitive colour rhythms in serial systems, including up to seven distinct colours.

Standing before these vibrant works evokes physical sensations as the viewer connects with colour and the materiality of paint. The buzz in the room is palpable, as colour vibrates within the works themselves, between each discrete work and between each painting and the spectator. This group sets a precedent for Tousignant’s work from this point forward, “mak[ing]” as he said, “painting … pure sensation,” which was his intention.

Claude Tousignant, Gong 64, 1966, acrylic on canvas, 164 cm in diameter. Collection of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. Photo: Guy L’Heureux. Courtesy Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

As dramatically as Tousignant shifted from organic form to exclusive use of the hard edge, he shifted to the monochrome. After the physical sensations evoked in the gallery of circular paintings, the monochromes and later circular works are quiet and perhaps less complex, both in palette and surface. The mature Tousignant is there, making diptychs and monochrome paintings in muted tones that simplify relationships among elements and consider the space they inhabit. To me, these works suggested quiet contemplation and consideration rather than vibration and sensation. The diptych format addresses spatial distance between the two components, around them and in relation to the spectator. The monumental, almost ceiling height, Monochrome jaune (Hommage à Érik Satie), 1981, embodies a meeting of Tousignant’s painting and sculptural interests. This vast yellow monochrome is 490 x 267 x 13.5 cm and sits on the floor, rather than hanging on the wall. It occupies the gallery space as an object rather than a painting, confronting the viewer as a two-dimensional medium articulated in a three-dimensional format.

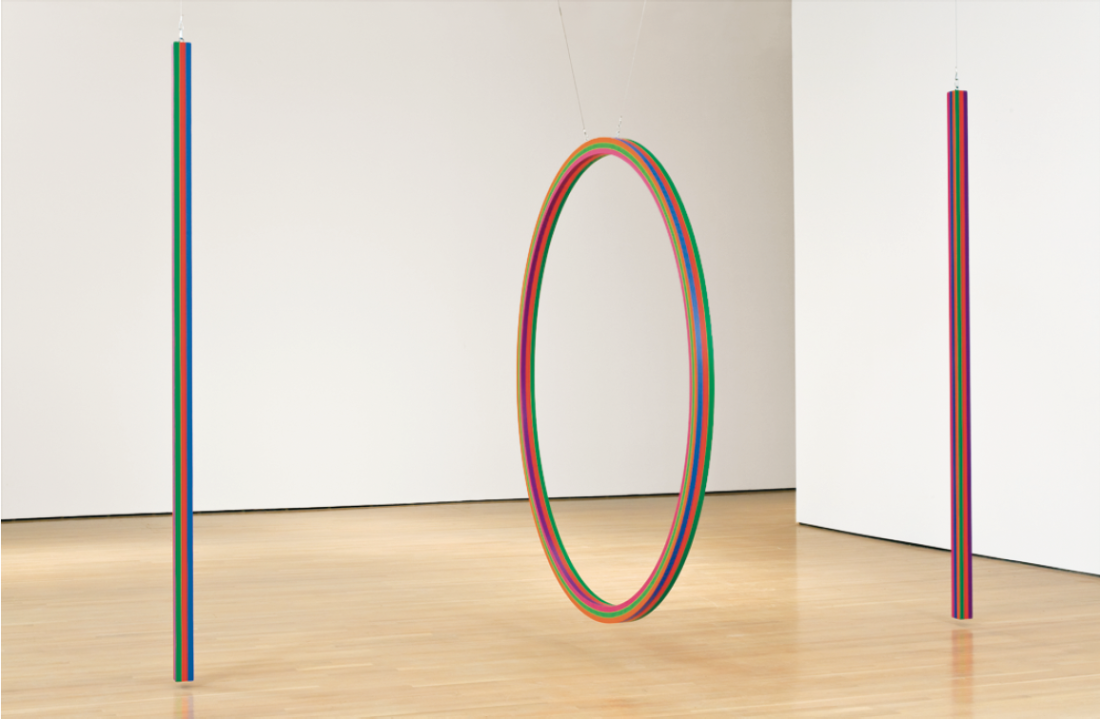

In recent works, Tousignant built geometric aluminium sculptures that suggest vertical mazes in space. He painted the aluminum with monochrome acrylics and invited the viewer to travel around it and look into it, offering a spatial interaction with form and paint. Dynamic in form, large in scale, almost three metres high, and monochromatic in colour, these sculptures present new directions for Tousignant.

This exhibition offers a rare opportunity to see a significant body of work, reinforcing the importance of a senior Canadian artist who has made important contributions to the practice of abstract painting at home and abroad. Pushing the boundaries between colour and form, Tousignant’s works illustrate the way in which colour itself can communicate by emphasizing its visual/perceptual and material qualities. Tousignant’s finely executed works show an unwavering commitment to fully exploring the abstract form, contributing enormously to abstraction’s visual vocabulary. ❚

“Claude Tousignant: A Retrospective,” curated by Paulette Gagnon and Mark Lanctôt, was exhibited at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal from February 5 to April 26, 2009.

Carol-Ann M Ryan is a Toronto-based writer, arts educator and collections manager.