Chronicles of a Disappearance

In Les lieux de mémoire, Pierre Nora tells us “Modern memory is, above all, archival. It relies entirely on the materiality of trace, the immediacy of recording, the visibility of image.” Showcasing five internationally acclaimed artists, “Chronicles of a Disappearance” at DHC/ART at once satisfies and subverts these terms. We are given a meditation on immateriality, distance and invisibility—the major constituents of absence.

Nora reflects on the relationship between history and memory, which invariably involves forgetting, but in viewing Taryn Simon’s An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar (Steidl, 2008), a variation of the question arises: What is the difference between forgetting and never knowing? The former term may suggest a potential for reclamation is being met with the trigger or trace—and the photograph functions well for both purposes. In Simon’s work, there is a focus on the latter, so that the photographs become evidence rather than reflection—they are about the strangeness of the present, not a rhapsody of the past. These well-lit and precise images, accompanied with text of a font so diminutive that we are necessarily drawn into the narrative through proximity, reveal the bizarre underpinnings of American society. We are not quite surprised by the revelations; in some way these photographs satisfy suspicions of the covert activity we so expect of a modern American mythology. This evidence has filled the void of ignorance (or is that innocence?), and these truths will not quickly be forgotten: cryogenics labs, models of the earth’s core, and selectively inbred tigers create a carnivalesque demonstration of American ingenuity’s refusal to be outdone by Mother Nature. Of particular resonance is the image depicting the enormous collection of goods confiscated within a 48-hour period at JFK Airport. It forms a grotesque still life replete with pigs heads and exotic fruits and serves as a monument of the paradox of human logic and sentimentality.

Omer Fast, 5000 Feet is the Best, 2011, digital film, 30-minute loop. Still by Yon Thomas. Courtesy the gb agency, Paris and Arratia Beer, Berlin.

In 5000 Feet is the Best, 2011, Omer Fast continues the investigation of American mythology, this time in a military context. Based on interviews with a real-life and a fictional Predator drone operator, Fast’s slickly produced film is a hybrid of fact and fiction, which plays out in a post-modern ellipse of chronologically broken segments. This is a multi-layered digression on absence, beginning with the sinister item of the aerial drone itself. Described as “small, white and almost invisible from the sky,” the drone imitates absence as it surreptitiously surveys and attacks from an aerial vantage point, which “doesn’t flatten things, but makes them sharper, their relationships clearer.” Unsurprisingly, the fictitious reenactment of the interview is more dramatic than the non-fiction account, which is told by an unidentified monotone male voice. However, the adage of truth being stranger than fiction reigns supreme. The operator, suffering from what he terms “virtual stress,” which nonetheless physiologically manifests itself as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), reports, without missing the irony, that one of the favourite pastimes of the drone operators is to play video games. He notes that unlike a video game, the flashbacks associated with PTSD cannot be switched off. Without the testimonial authority of the eyewitness perspective of aftermath, “virtual” traumatic memory necessitates a filling-in to make the narrative complete. To this end, the operator inserts imagination and conjecture, completing the mission, and in turn creating the recurring nightmare, which one can only imagine plays out in his head like the broken loop of a film Fast presents to us.

In Opus, 2005, Cuban artist José Toirac considers other enigmatic issues of nation and culture in relation, but not endemic, to Cuba. This is a conceptual single-screen work, consisting of white numbers that appear on a black screen, paired with an edited audio recording of an impassioned speech by Fidel Castro. Through the editing process Toirac “disappears” all words in the speech, so that all that remains is a statistical incantation of averages, gains and (one can assume) losses. With the context removed it evokes questioning, but is never questioning in itself. Never do we sense a rising intonation in his voice that would suggest interrogation or doubt as Castro works towards a crescendo that never arrives, reaffirming that conviction is the propulsion of progress, either real or imagined.

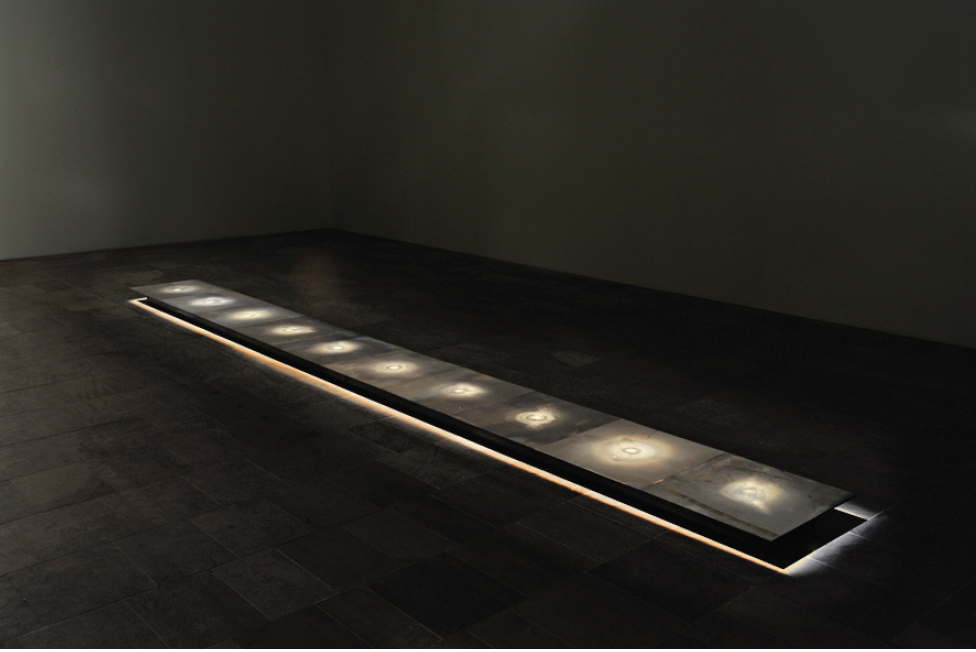

Teresa Margolles, Plancha, 2010, installation with 10 heated steel plates and water from the morgue, 300 x 600 x 60 cm. Exhibition view of “Frontera,” 2010, Kunsthalle Fridericianum, Kassel. Photograph: Nils Klinger. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich.

In Latin-American Spanish, the word desaparecido (disappeared) has taken on meaning as both a noun and a transitive verb, largely as a result of campaigns of terror in certain Latin countries, such as the infamous Operation Condor in the Southern Cone of South America in the 1970s. Teresa Margolles’s piece, being both active and passive, addresses both forms of this word, which in her native Mexico automatically assumes violent and sinister connotations. In Plancha, 2010, water drips from the ceiling onto a row of 10 heated steel plates, evaporating instantly with a pronounced hiss marking the change of state. This passage takes on more resonance from the fact that the water has been “sourced” (a term we are used to associating with this fluid essential for life) from a morgue in Mexico City. Undoubtedly, the water has been used to cleanse not only the corpses of those who died a “natural” death, but also those who met a more nefarious end.

The final work to make up “Chronicles” is Philippe Parreno’s June 8, 1968, 2009. Shot in 70 millimetre and digitally projected onto a huge wall-sized screen, this gorgeous seven-minute film, infused with highly saturated colours and sharp and melancholic sounds of the train’s machinations, recreates the journey from New York to Washington D.C. carrying assassinated Senator Robert Kennedy’s coffin. The film is loosely based on the RFK series by Magnum photographer Paul Fusco, who was on the train that day, capturing images of the countless bystanders who had come to pay respects. In essence, the film is a series of tracking shots from the perspective of the train—motionless bystanders caught in some infinite stance of remorse, their stillness accentuated by the wind-bent grass or the movement of tree limbs. Compared to the Fusco archive, groups of rail-side mourners in Parreno’s film are generally paired down. Indeed, the most poignant of the images are the solitary mourners—a boy at an intersection on a bicycle, a young woman, alone, unexpectedly bikini-clad along the tracks. At times, in Fusco’s photographs, the gazes of the witnesses meet his lens and at others, trail off to the length of the train, seeking something they know to be invisible. However, the bystanders’ gaze in Parreno’s film seem to meet our own, as though we are standing on the other side of nothing, and through this meeting the exchange between art and audience occurs.

As much as it is an elegy to death, “Chronicles” also acts as a memorial, preserving remembrance and guarding against that greatest loss, which is forgetting. ❚

“Chronicles of a Disappearance” was exhibited at DHC/ART, Montreal, from January 19 to May 13, 2012.

Tracy Valcourt lives and writes in Montreal.