Christos Dikeakos

Since architecture, like all the arts, is host to strains of egotism, each building becomes a proposition, an individual philosophy made concrete. We see in the marble sweep of a train station the grandeur of some proposed goodbye, and the best private homes are often delivered to wealthy clients complete with furnishings and paintings, as though the architect would design a lifestyle in addition to a house. But the built environment does more than express some individual Fountainhead vision: it informs our communal lived experience. This dual duty—to the individual and to the collective—gets smartly assessed in a series of new photographs by Vancouver-based artist Christos Dikeakos. Ten large lightjet prints were displayed recently at Catriona Jeffries Gallery.

Dikeakos has always been interested in place, in particular the usurpation and re-imagining of places, and Vancouver is a prime target for such a study. Continuing this thread in his latest work, he made himself a documentarian of the Olympic Village construction along the South East hub of False Creek—a contentious project figured in the media as both a financial disaster and a paragon of humanitarian development (due to a raft of LEED certificates and a fair chunk of non-market housing). In a city obsessed with real estate and the dilemma of homelessness, the Olympic Village becomes a fulcrum of civic identity.

When Dikeakos trains his camera on the site, which has been pegged over with a dozen cranes, what he pictures looks at first like a nothing-space on the fringe of blustering urbanity—a dead zone that almost calls up the deserted ambitions that now gird Dubai.

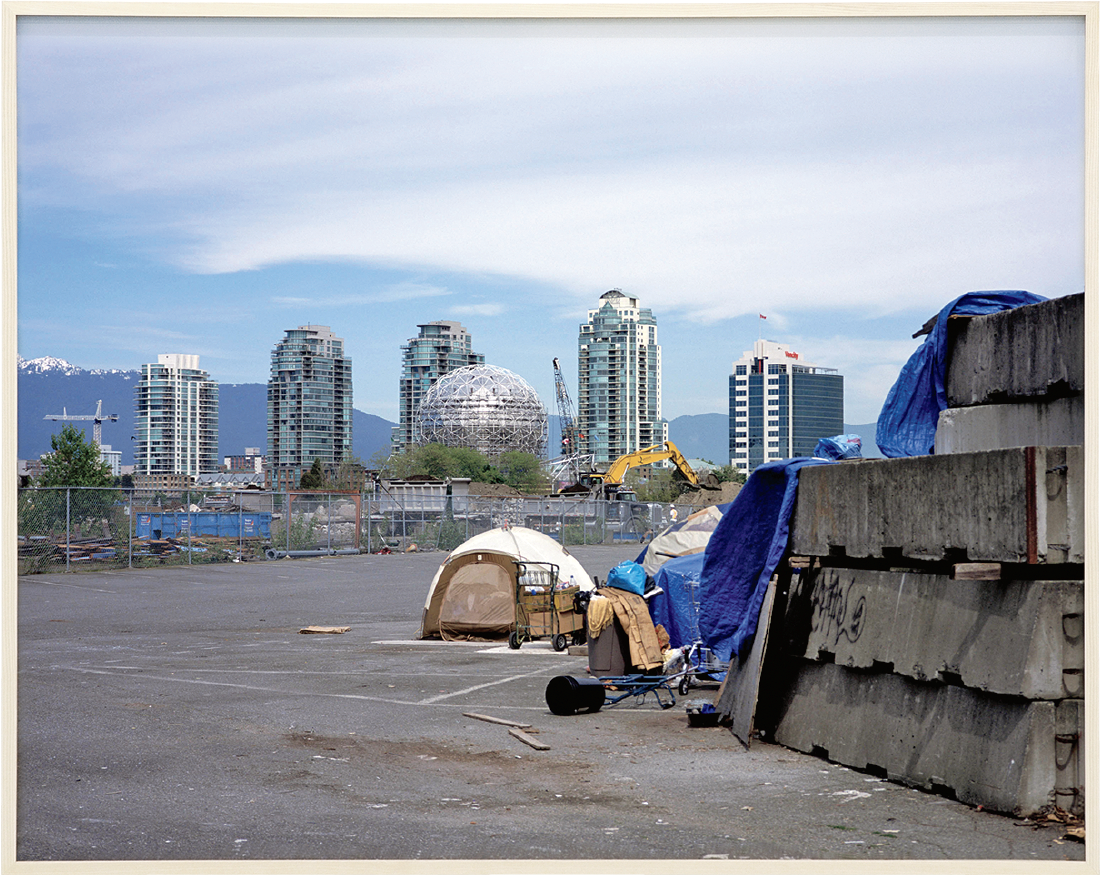

Christos Dikeakos, Squatter’s Tent, Olympic Village, 2007–2009, LightJet print, 48 x 60”. Courtesy Catriona Jeffries Gallery, Vancouver.

The show’s most dramatic piece, Window View, Main Street, a construction site viewed through the frame of a workshop window, is a collage of two photographs (one of the workshop window, one of the village beyond) that becomes evident only after a moment of analysis. Purposeful static, paired with a granular quality in some of the images, lend the pictures a painterly quality; razor-sharp digital resolution is not a priority. Indeed, Window View, Main Street was referred to by Dikeakos at his opening talk as a kind of history painting (a parallel that Vancouverites are used to; Jeff Wall’s work often fits better in the history of painting than photography). And speaking of history—in the mid-ground of that grand and clamorous image, one can spy the Chrysler dealership that went under once the recession hit. Place and time are inseparable, and when Dikeakos calls Window View, Main Street a history painting, I think he means it literally—this is a picture of a moment and a place that will come to define Vancouver’s identity. In a city so hybridized, young and mongrel, such defining images are a precious few.

Squatter’s Tent, Olympic Village provides perhaps an obvious juxtaposition between a transient shelter at the edge of the construction site and the luxe accommodations that will shortly displace it. (Dikeakos pictures makeshift shelters three times in the exhibit.) Another easy parallel: the geodesic dome of Science World, a leftover from Vancouver’s last global party, Expo ’86, neatly mimics the shape of the squatter’s tent. Beside the tent, a blue tarp cascades down blocks of piled cement, as though mockingly referring to the blue mountains and waterfalls—the postcard Vancouver—that lie beyond. There are, in fact, many points in these works where the grandeur of nature, always visible through downtown Vancouver’s strictly maintained “view cones,” rubs harshly against the constructions of humans. Scotch Broom, in particular, gives a great burst of insistent, floral plant life in the midst of a grey development.

If all these works are mapping the physical landscape, The Room, 3 Vets serves to map a psychic one. In the exhibit’s only interior image, a man is seated behind a glass display case surrounded by First Nations masks and paddles that are cheaply mounted on the walls around him, all for sale. Displacement is still resonant here, but Dikeakos is making us work a little harder. He never lets Vancouver be what it wants to be—a shaken Etch-a-Sketch, blank and promising. “Look,” he says, “you can never be the first one here.”

In an exhibit so devoted to the politics of place, the viewer can’t help but notice the picture you get upon exiting the gallery, which is itself sited blocks from the Olympic Village, the cranes visible from the gallery’s doorway. As well as its international standing, the Catriona Jeffries Gallery has served as a definer of the city it sits within. And Dikeakos has, through that gallery, delivered work intimately tied to the site of its original display; wherever these images now travel, they’re going to be nostaligic nomads, tethered to the imaginary ground called home. ❚

Christos Dikeakos exhibited at Catriona Jeffries Gallery in Vancouver from March 26 to April 25, 2009.

Michael Harris is an editor at Vancouver magazine.