Christopher Pratt

When I was in Newfoundland years ago, seeing the light delineate window frames, horizon lines, blades of grass and waves on the water with equal precision provoked a shock of recognition. This was Christopher Pratt country. To perceive the work of an artist in an actual environment is not an unusual experience, but this particular recognition distinguished itself in several ways. First, I had never seen a real Pratt painting at the time, only reproductions in art books and magazines. Pratt’s images of empty rooms, with windows that provide glimpses of sea and sky, have become part of the Canadian cultural consciousness without their having had much museum exposure outside the Maritimes. The current retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada is the first large show since the Vancouver Art Gallery organized a retrospective travelling exhibition in 1985. Second, it was not picturesque fishing villages, icebergs or windswept rocks that I recognized from Pratt’s art; he has always managed to avoid such clichéd subject matter. My shock of recognition was based singularly on the ephemeral matter of light and shadow. I had thought of Pratt’s use of light as a personal expressive device. In Newfoundland I realized that he has not invented but captured this magical, low, northern light that draws long and sharp shadows on the land and colours the skies in a haunting sfumato.

Pratt’s work cannot be separated from Newfoundland, the place where he was born and has lived most of his life. But his particular regionalism serves foremost to accommodate the contemplation of larger philosophical questions. The openness in this part of the world, Newfoundland’s ever-present horizon and the light that conjures things from nothingness into being, sets a stage on which to project an intimation of infinity and our small place in it.

In her catalogue essay, curator Josée Drouin Brisebois argues convincingly that Pratt’s works have a bearing on specific political events, such as the ban on cod fishing and the abandonment of fishing outports that began with resettlement in the 1960s. But to my mind, Pratt’s “political” paintings are as much about the loss of vision that occurs with the deterioration of the natural landscape as they are a lament about actual physical devastation and loss of livelihood. Winter at Whiteway, 2004, which shows a tattered Canadian flag (a rare sign of decay) on an abandoned wharf, is perhaps the most explicitly “political” painting in the exhibition. Clearly, this painting refers specifically to Newfoundland’s troubled fishing industry and its frustration with federal politics, but it also links this muddled stage with a loss of vision: the ocean’s horizon is obstructed by the icy rocks of a breakwater. What is lost in the ongoing lifestyle changes in Newfoundland, Winter at Whiteway suggests, is not just access to the sea as fishing ground, as a means to make a living, but also a landscape on which to project a longing to go beyond the self, to make life meaningful.

Christopher Pratt, Pedestrian Tunnel, 1991, oil on canvas, 102.9 x 190.5 cm. Collection London Life Insurance Company. Photographs courtesy The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

Can we still make sense of our being-in-the-world when we dismiss its vastness and surround ourselves mainly with constructions of our own making? Deer Lake: Junction Brook Memorial, 1999, a large painting of a hydroelectric power plant, is as much a lament about the harnessing of nature by culture as it is about the substitution of artificial for natural light. The darkness of this painting, the prominence of the building that obscures much of the sky and the water, suggests a blocking of vision, a loss of openness to the world that would accommodate existential contemplation.

In contrast, Pratt’s Gulf of St. Lawrence, 1976–1984, shows an open vista of sea and sky. This image may seem to answer an idealist desire to lose oneself in this vast emptiness and leave behind the decay and death of our embodied existence. But a low barrier on the quay in the foreground reins in such metaphysical longing. It serves to remind us of our physical presence in the world just as surely as does the figure in C.D. Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea. In Friedrich’s early 19th-century image—the inescapable precursor of Pratt’s Gulf of St. Lawrence—the monk, who is seeing, or looking, forms an intrusion in the total view, for himself as well as for the viewers. The monk is a stain on the “empty” canvas, reminding us that from our embodied vision, a total emptiness can never be perceived. Pratt underlines his own skepticism about the boundlessness of vision by clearly indicating the position of the painter and—by implication— the viewer, on the shore.

It is this invisible presence of the seer that haunts many of Pratt’s paintings. I am particularly drawn to his “empty” rooms, a subject matter that persists from the early seventies (Cottage, 1973) to the present (Storm on my Porch, 2002). The empty buildings stand in for the viewers. Their walls, doors and windows restrict vision, but they also let in the light that makes vision possible. Pratt’s play with reflections and shadows, with inside and outside spaces, shows a poetic reciprocity between seer and what is seen. The newer road paintings, such as the series “Driving to Venus,” 2000–01, have a similar complexity. The front lights of the car illuminate the road; the viewer is not seen, but must be present in the car. The landscape the car moves through changes continuously, but vision remains bounded by the vantage point of the windshield and the driver behind it.

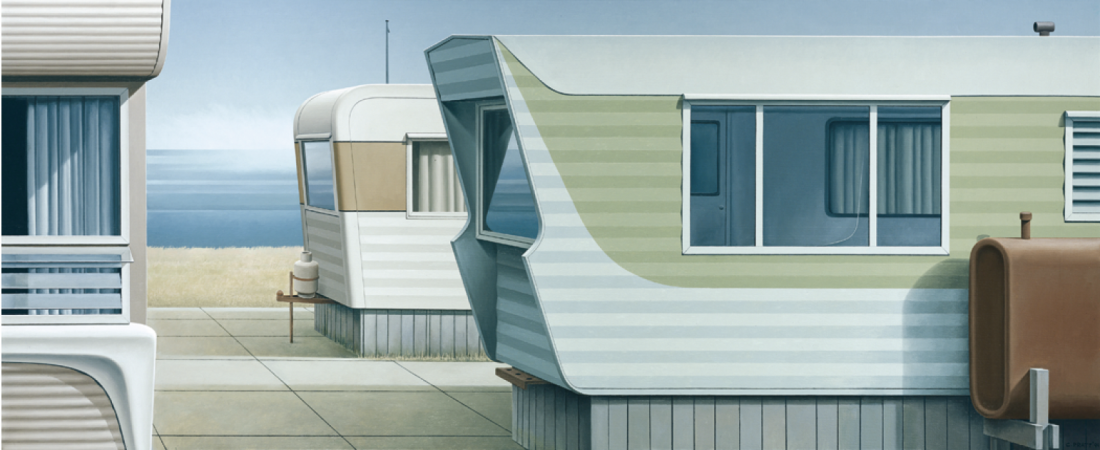

Christopher Pratt, The Americans: Off-Base Housing, 1999, oil on canvas. Collection John Royce.

Despite Pratt’s abstraction of reality, his Mondrian-like formalism, he is no idealist, no spiritual dreamer. He is, in fact, always there, squarely grounded in the scene, if not in the painting. The lack of the figure and the sparse order of the views acknowledge a desire for a spiritual void, but Pratt transforms this desire into an investigation of embodied vision and consciousness, those impediments of nothingness. Pratt’s rooms bring home the words of philosopher Merleau-Ponty: “he who sees is of it and is in it.”

Such porous vision is not present in all Pratt’s works, however. Works such as Bear Cove, on the Strait of Belle Isle, 2003, and East Bay, Port au Port Bay, 2003, show windowless shacks surrounded by snow, isolated objects that do not acknowledge any other presence. As aesthetically pleasing as these paintings are, they demonstrate a far more oppositional vision.

The sense of my gaze hitting the object on the canvas becomes an old feminist issue when these objects are nude or partially clad women who remain oblivious of the viewer. The absence/presence of the viewer, which in the paintings of empty buildings elucidated the to-and-fro of vision, here only creates an uneasy sense of voyeurism.

In Pratt’s more recent work, a longing for timelessness has been accompanied by an acute sense of the irreversibility of time, the sense that, in his own words, “life is not a rehearsal.” Where Pratt used to work from sketches saved over the years, his newer works are more immediate, the result of recent experiences, of things recently seen. The wild range of Newfoundland’s weather, from blizzards to sultry summer nights, now plays a larger role. Titles have become more specific and more details are included, as in Crab Plant with Cat Tracks, 2002. Although marks of decay remain rare in Pratt’s work, some rust stains and other signs of wear appear in Argentia Bunker, August, 1989, and Military Presence, 1999. “It comes down to this,” Jeffrey Spalding observes wisely in his introduction for the catalogue, “we can perhaps hope to catch a glimpse of the infinite. With the passage of time, however, it becomes inescapably clear that we do grasp the nature of the finite.” ■

“Christopher Pratt” was mounted by the National Gallery of Canada, where it was on exhibition from September 30, 2005, to January 8, 2006. The tour will continue to a number of galleries in Canada, concluding in Winnipeg in October 2006.

Petra Halkes is an artist and writer living in Ottawa.