Chris Kline

Walking into an empty room, I’m usually tempted to feel out the room’s size, to intuitively take it’s measure. This “measuring” may be an endeavour of orientation, of fitting my senses to the space or vice versa. “Sizing up the situation.” It’s a “try,” in the sense of early usages of this term deriving from the Old French “trier,” meaning “to sift,” a word often used to name a sorting-out activity, separating above from below, open from closed, the near from the far, the here from the there, the now from the then and finally the true from the false.

Another use of “try” dates from 1539 ad where it meant “to distress,” as in subjecting to some strain, to put something or someone under pressure or tension. This sometimes happens to us in the company of individuals who remain silent in our presence, failing to be engaged in our attempts at small talk. This has often been the strategy of avant-garde art works as well: John Cage’s 4’33” of 1956 presented the occasion and expectation for a musical performance but replaced the music with the “noise” of distant traffic entering through windows opened by the composer. These uses of emptiness have often functioned to throw attention back onto our processes of attention and the means we use to “weigh” a proposition. Again, these procedures are “trials” or perhaps more accurately, essays, following again the Middle French essai, meaning “trial, attempt, essay.” These terms are all variously connected with our ways of experiencing art insofar as they all imply questions of judgment, weighing of values, assigning positions and meanings.

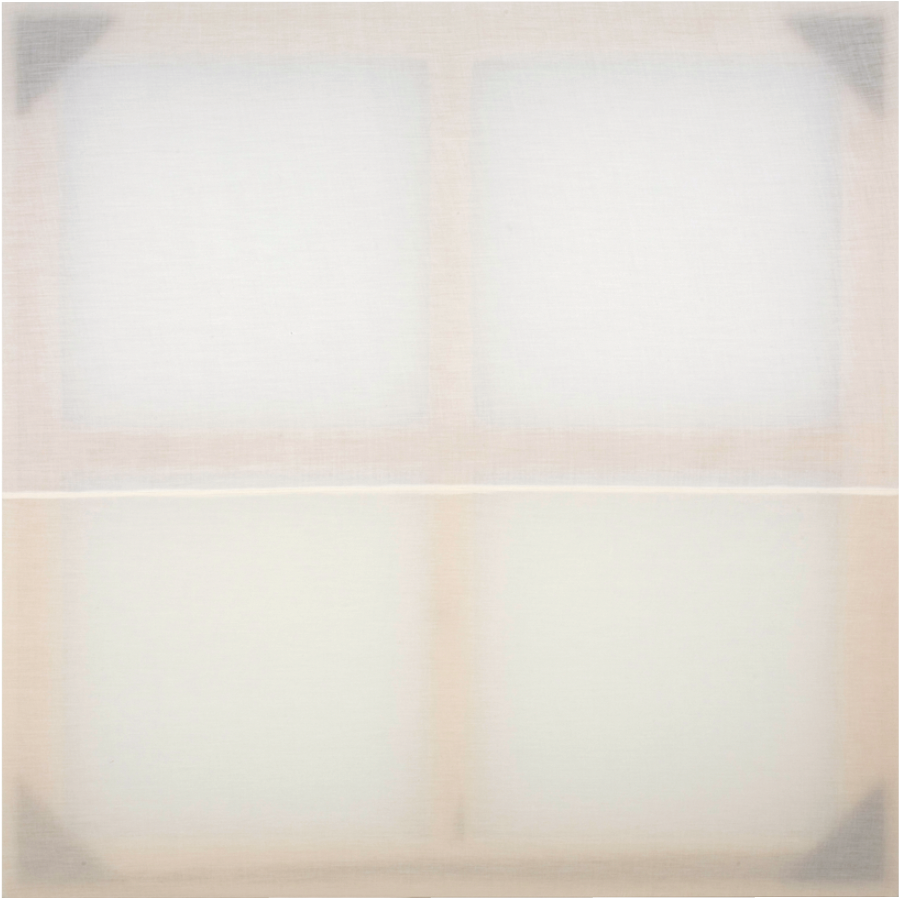

Chris Kline, By The Time It Gets Dark, 2008, poplin, thread and wood, 48 x 48”. Courtesy Galerie René Blouin, Montréal.

In artworks as simplified as these eight paintings by Montréal artist Chris Kline, the theme of judgment arises quickly because painting is such a tried and true territory. However, this exhibition is remarkable for the path it creates in expanding its field of painting while paradoxically delimiting painting by way of its material practice.

For one thing, these stretched rectangular canvases are entirely devoid of paint in the empirical sense, yet experientially one may well see and describe these works as painted canvases. Close examination also reveals that these canvases are actually fragile cotton poplin where we would expect opaque linen. This explains the visibility of the stretchers with their cross braces, which haunt the otherwise empty rectangles. And yet, “empty” is not entirely accurate either, for each painting features a distinct horizon line formed where two slightly different poplin fabrics meet in a folded, sewn seam slightly below the horizontal midpoint of each painting. This seam in each painting is only relatively straight, having been drawn “freehand” with the sewing machine.

It is these factors, the grid created by each painting construction along with the presence of a horizon line that has persuaded me that measuring is the proposition advanced here in Kline’s exhibition. It is this that locks the exhibition and its space into a relationship with architectural place and with a discourse regarding the significance of such a proposition. As with architecture, these paintings participate in a relationship with place, but as paintings, of course, this occurs by way of the landscape convention. Kline’s paintings present an interesting variant with their machine-sewn, hand-drawn seam that forms a horizon line, a line that refuses any illusion of depth, remaining right on these surfaces of finely woven cotton.

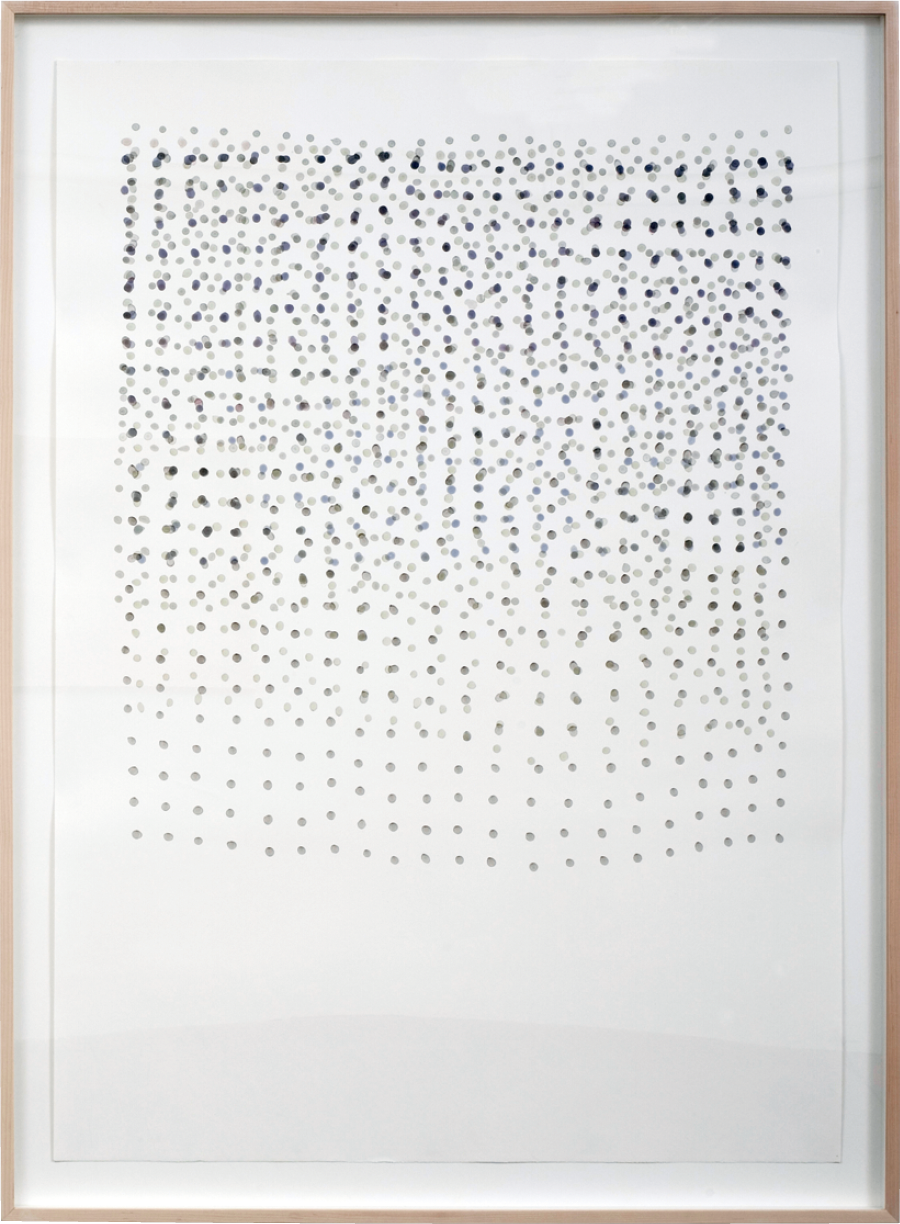

Chris Kline, Motes 2.5, 2008, watercolour on Stonehenge paper, 50 x 36”. Courtesy Galerie René Blouin, Montréal.

These ephemeral paintings may be notable for their perceptual fragility: they are tense, intimately hand-made and very beautiful. The refinement they bring to play on the materiality of painting risks the painting’s disappearance into sophisticated décor. That this doesn’t happen is due to their sharing in the origins of architecture, a dialogue foregrounding “the measure,” a sort of cosmology of architecture in which above and below, sky and earth are the principles. Elizabeth Grosz, a philosopher writing extensively on architecture, says, “ … the first gesture of art, its metaphysical condition and universal expression, is the construction or fabrication of the frame” and that “ … architecture does little other than design and construct frames, architecture being the constitution of interlocking frames, frames that connect with, contain and are contained by other frames.”

The works in the exhibition, as do Kline’s works in general, present us with the difficult pursuits of slowness, vagueness and richness that accompany experiences of transition, the space of the horizon being a site of such transitioning. Perhaps the challenge Kline is faced with is that of perversity in the here and now, in the work’s propensity to reverse and become pure abstraction. ❚

“Chris Kline” was exhibited at Galerie René Blouin in Montréal from November 8 to December 20, 2008.

Stephen Horne is an artist and writer based in Montréal.