Che Guevara: Revolutionary and Icon

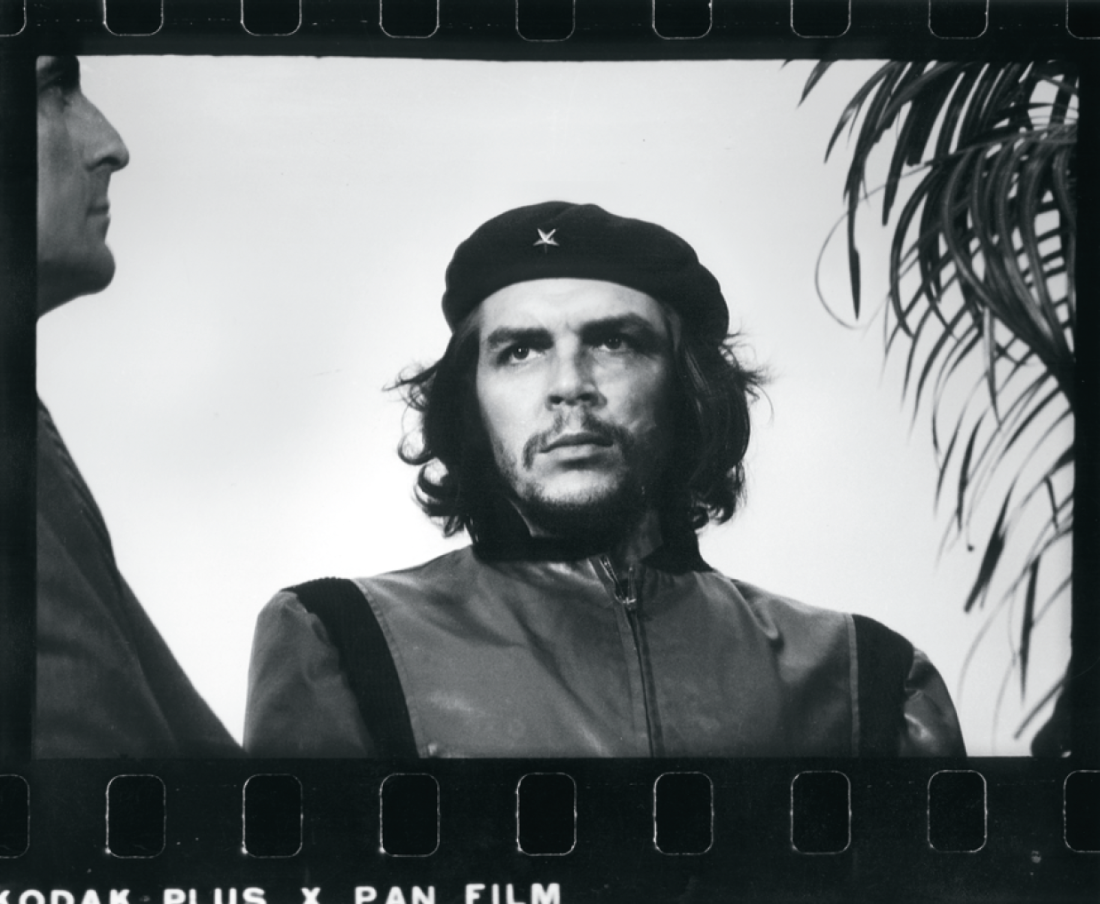

The Korda photograph of Che Guevara is among the most reproduced photos ever taken. The result of a snapshot moment at a funeral in Havana in1960, Korda’s almost accidentally captured image would come to stand, around the world, for revolution, change and what has been called “the good fight.” After Guevara’s assassination in Bolivia in October 1967, under suspicious circumstances involving the American CIA, the image spread rapidly. But what has happened to this picture in the intervening years, and why has it had such amazing longevity as a marketing icon as well as a sign of struggle against adversity? “Che Guevara: Revolutionary and Icon,” organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, sets out to answer these and many other questions by assembling examples of the myriad places and ways the Korda photo has been used.

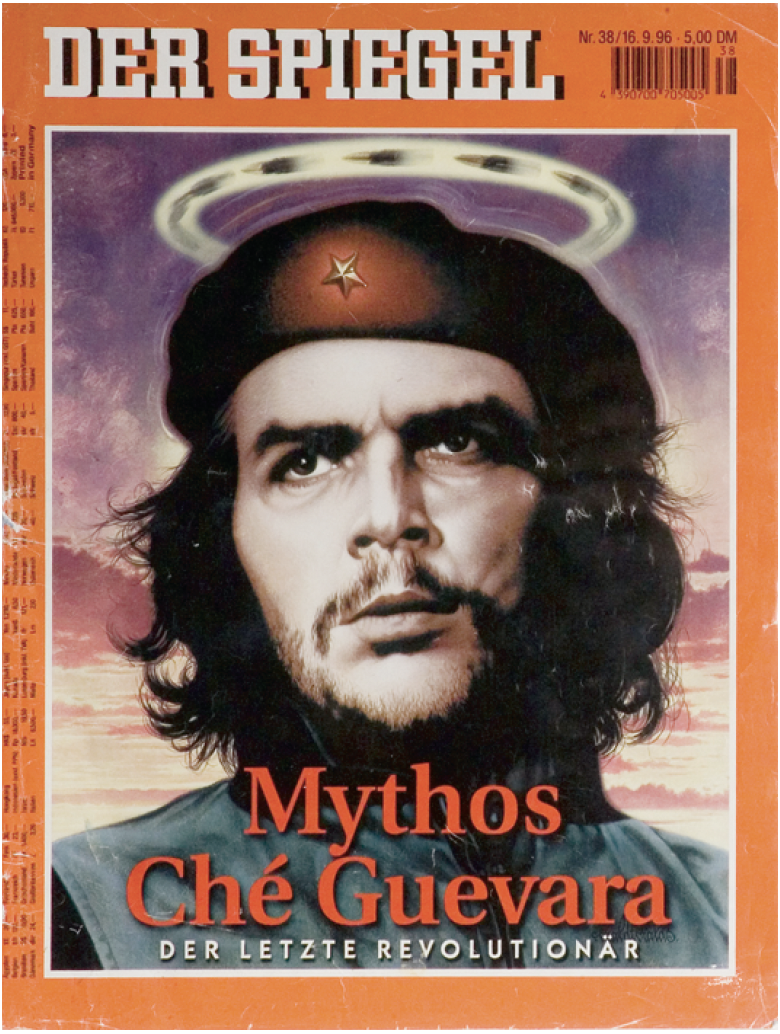

Myth of Che Guevera, Der Spiegel no.38, 16 September 1996. Collection: David Keenzle. Photographs courtesy of UCR/California Museum of Photography.

After Guevara’s death, the image became an integral graphic embellishment within the counterculture of the boomer generation. Spurred on by anti-American sentiment during the Vietnam War and the growing international meddling of US foreign policy, the Che image stood universally for opposition. As curator Brian Wallis points out in his catalogue essay, a number of key moments secured the Che image in the political imaginations of the time. Roman Cieslewicz’s Che Si was used as the cover for the October 1967 Opus International, an art magazine published in Paris before Che’s death, leading up to the student protests in ’68. The second image Wallis mentions is a poster from 1970 by the Art Workers Coalition in New York featuring Che and his quote: “Let me say, at the risk of appearing ridiculous, that the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of Love.” The sentiment was right for the rising youth movement protesting American imperialism.

Opening of the Saatchi Gallery, London, 15 April 2003, Martin Parr, Magnum Photos.

The photo’s familiarity made it fodder for the producers of culture, from album covers, comics and paintings, to labels for any product you can imagine. There is Madonna’s American Life poster from 2003, where she’s assuming the familiar pose, a Der Speigel cover from September 1996 that depicts Che as Christ with a halo, and in 1999 the Church Advertising Network in the UK ran a bus shelter poster ad called Jesus: No Wimp in a Nightie, where an image of Che with a crown of thorns appears above the caption “MEEK, MILD, AS IF: Discover the real Jesus.” In Australia, a candy company promoted a product called Magnum Ice Cream—Cherry Guevara: “The revolutionary struggle of the cherries was squashed as they were trapped between two layers of chocolate. May their memory live on in your mouth!” At the moment of writing, there are 1048 Che items for sale on eBay. And then there is always www.che-mart.com, where Guevara is heralded as the world’s greatest T-shirt salesman. One of the most pointed images in the exhibition, Patrick Thomas’s American Investor in Cuba, 2002, first appeared in the financial supplement of La Vanguardia in Barcelona. It’s the Che image made of logos from international corporations like CNN, hp, Dell, Coke, Intel, Disney, Kellogg’s, etc.

Guerrillero Heroica, Alberto Korda, March 1980, Havana, Cuba. Courtesy of the Korda Estate.

Che is a super-logo in a logocentric world, an archetype and icon that has more recognition value than real content. Its perfection is due in part to the pop aesthetic of the ’60s that reduced the image to a graphic sign, a pattern easily reproducible in any medium. Its migration, or repurposing, from one context to another brings with it a hint of subversion even though it becomes just another brand. The golden arches make us think of food, always the same, no matter where we are in the world. Coca-Cola is the universal thirst quencher, and Che is the edge everyone wants to think they have—a modicum of control where “no” is a mere whisper in the face of “Yes, we want more!”

The Che image is not alone. There are others like Mao Tsetung, Karl Marx, Marilyn Monroe, Einstein, all with instant recognition, but none of them speaks to individualism the way the Che image does. They lack the romanticism, the idealized hero connotations that people want to feel, and exhibit—some evidence they have control over their lives. The Western ideal is that individualism is a human right; it’s also necessary to prove ourselves interesting, cutting-edge, cool. In the end, though, it appears that maybe the most revolutionary thing we can do today is deciding what to buy or sell. ■

“Che Guevara: Revolutionary and Icon” was exhibited at Victoria and Albert Museum in London from June 7 to August 28, 2006.

Randall Anderson is an artist and writer living in Montreal. He recently received a commission for a public sculpture at Concordia University’s Fine Arts building.