Charles Burchfield

What started out Van Gogh ended up Bosch. It may not be on record, but Charles Burchfield was the first modern artist. At least, the first American artist to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York when it first opened in 1930. Strange for an old fashioned Betty Crocker watercolour painter you can compare to Norman Rockwell.

Here at the Burchfield Penney Art Center in Buffalo, New York, this travelling show, which began its tour at The Hammer Museum in LA and travels next to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, is more than just tormented, Depression-era art.

But wasn’t Charles Burchfield kind of boring? It’s true for the video game-addled, eight-email-account, social media 20-something who hasn’t the time to tweet never mind text, but what draws the Artforum-obsessed art scenesters is the rock star curator, New York artist Robert Gober. This is the man who represented America for the 49th Venice Biennale in 2001, whose meaty, stark sculptures have adorned five Whitney Biennials. He shows at the Matthew Marks Gallery in New York alongside kingpins Gary Hume and Ellsworth Kelly—and he does leave trails of stardust wherever he walks.

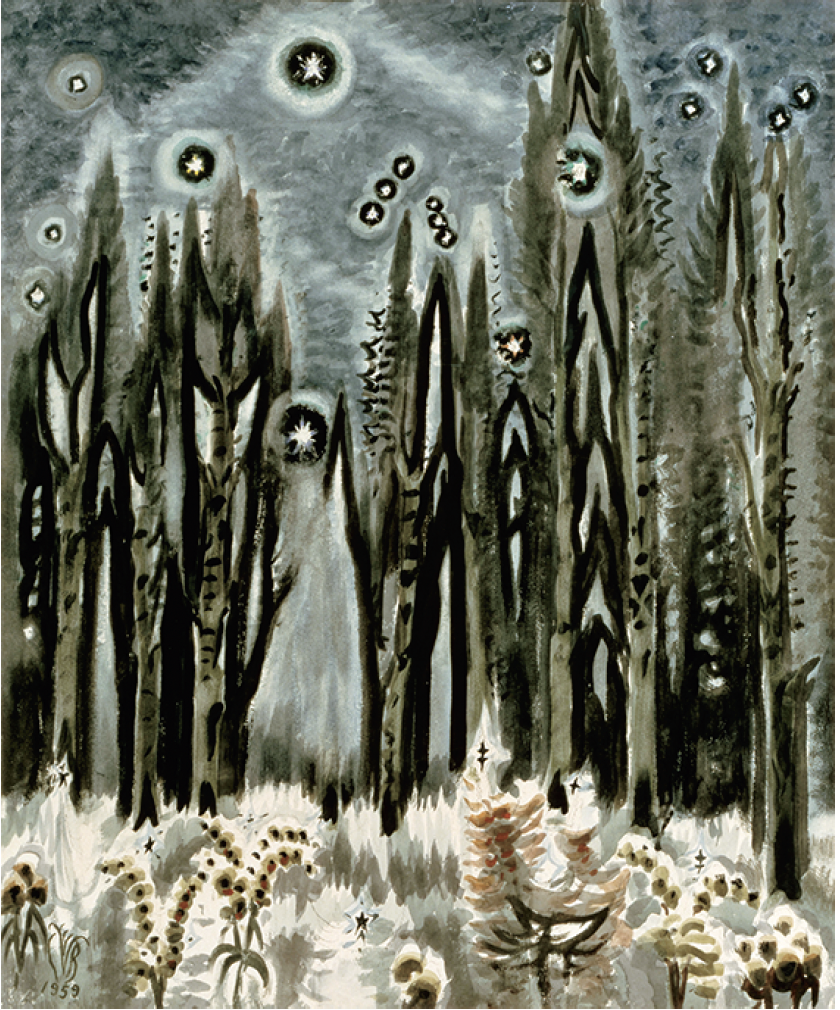

Charles Burchfield, Orion in December, 1959, watercolour and pencil on paper, 39 7/8 x 32 7/8”. Gift of S C Johnson & Son, Inc. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, and Burchfield Penney Art Center, Buffalo, NY.

So what is he doing in Buffalo? And how exactly did this David Bowie art star manage to match up beside what feels like…Kenny G, as one of “America’s top five contemporary artists?” In an interview, Gober sheepishly declines the stature and cites Jeff Koons and Cindy Sherman as the real art stars.

But this unsolved mystery all came about as most things do in the New York art world: at a dinner party. Sometime last year, Gober and his partner, the artist Donald Moffett, had a long-time friend and director of The Hammer Museum, Ann Philbin, to their East Village apartment for dinner. She spotted a small work by Burchfield in their home, a drawing of curtains and a window (which Gober paid $800 for at an auction), and soon after they chatted about Burchfield’s legacy, the retrospective was born.

The 80-work show features thoughtful watercolours, oils and drawings of forests and trees that, at times, could pass for Emily Carr’s long lost step-cousin.

A set of yellowing graphite drawings at the entranceway reveal Burchfield’s surrealist side, like Insanity from 1917, two nipples kissing one another, or Dangerous Brooding, also 1917, in what seems to be a bruised fist raised in the air like a cartoonish black cloud. Or in The East Wind, a work from 1918 that calls to mind a still from a black-and-white Disney film, showing a huge Scream ghost face brushing up on a house like the cloak of death itself. So it’s not all Group of Seven style. Though there is a glimpse of Little House on the Prairie, at least, in the mock-up of his former studio. Set up like something we’d catch at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto is a life-sized diorama with an easel, wooden rocking chair and taxidermy owl in place (the bird of knowledge later makes a cameo appearance in Midsummer in the Woods from 1951–1959).

Charles Burchfield, Two Ravines, 1934–43, watercolour on paper, 36 1/2 x 61 1/8”. Gift of the Benwood Foundation. Courtesy Hunter Museum of American Art, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Burchfield Penney Art Center, Buffalo, NY.

It also isn’t all limp-wristed pansies and wildflowers. When he was sworn into the army in 1918, Burchfield designed army camouflage for World War I. And a set of globby green-and-yellow watercolours are in the display case (they also show a more whimsical side he explored later in life). His response to the war was a little half-baked. “I wasn’t touched by the war at all,” wrote Burchfield in a letter to Frances M Pollack in December 1934. But somewhere on the battlefield, a bell went off. You first notice Burchfield’s spiritual awakening in Afternoon in the Grove from 1916, where an amber sun crackles through like a fireball in a thick swamp of trees. And it only gets brighter from hereon in. After he hit a mid-life crisis at the age of 50, Burchfield went a little Where the Wild Things Are. Letting his imagination run wild, he produces work that goes from murky evergreens to exotic palm trees (no, he did not decamp to Florida). Burchfield, it appears, had a little Bosch in him. He swapped the boring houses and burning barns he painted earlier in life for the good stuff that makes you want to drop acid and crank up the Grateful Dead.

Autumnal Fantasy from 1916–1944 is the most psychedelic work in the show—yellow-gold ochre trees shooting out rays of what look like parenthesis, Blue Jays hopping about and curly fries basking in a glowing UFO sunlight. Are those green frogs in the foreground? (Or was it cartoon moss?) Did he dabble in psychotropic drugs? The rumour is that Burchfield did take a lot of prescription drugs, especially morphine. But it was based in his belief system. While he grew up Methodist, he later turned to Pantheism. In this sprawling retrospective, there are poignant key pieces and the rest are just postcards. That said, The Four Seasons, 1949–60, shows Burchfield at peace with himself. This wintery cold and snow-encrusted Wizard of Oz landscape shows, off in the distance, a gateway to what feels like Nirvana. He seems to have hit the spiritual jackpot and it’s the last piece in the show.

Burchfield looked like a banker. He dressed like one too—bespectacled, in a business suit and upholding a menacing grin (there is a black-and-white portrait of the artist in the front hall of the gallery, and he strikes a resemblance to psychic and Burchfield contemporary Edgar Cayce). He wasn’t very flashy; he is often called “under-recognized.” But he was friends with Edward Hopper. So the shadows he painted in The East Wind could have been a reflection of how he felt about himself, standing in the shadow of a bigger art star.

But here, the New York art star Robert Gober takes a step back so Burchfield can step forward. And that could have been the enlightenment Burchfield was waiting for all along. ❚

“Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield” was exhibited at the Burchfield Penney Art Center in Buffalo, ny, from March 7 to May 23, 2010.

Nadja Sayej is the host of ArtStars, is a contributor to The Globe and Mail and is the founder of the Toronto Alliance of Art Critics. She lives in Toronto.