Charlene Vickers and Faye HeavyShield

Vancouver’s Contemporary Art Gallery’s (CAG) pairing of two solo shows, “Ancestor Gesture” by Charlene Vickers and “New Work” by Faye HeavyShield, appeared, on first viewing, strangely unequal. The Vickers exhibition took the form of a mini-survey of more than a decade of her artmaking and included eight substantial works, including installations in the CAG’s window galleries and at a nearby rapid transit station. HeavyShield was represented by two new works only—a long, thick, red-beaded cord laid out on a white plinth and a series of small drawings executed on intentionally un-artful paper. Formal and thematic reverberations did occur between the two shows. HeavyShield, it has just been announced, is the recipient of the 2021 Gershon Iskowitz Prize at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Charlene Vickers, installation view, “Ancestor Gesture,” 2021–2022, Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver. Photo: SITE Photography. Photographs courtesy CAG, Vancouver.

Vickers, an Anishinaabe artist from Wauzhushk Onigum First Nation in northwestern Ontario, was born in Kenora and raised in an adoptive family in Toronto. Based for many years in Vancouver, she acknowledges the unceded Coast Salish lands on which she dwells while also employing her sculptures, paintings, videos, mixed-media installations and performance works to reclaim and express connections to her ancestral home and culture. Among her paintings are colourful geometric abstractions, inspired by Anishinaabe quillwork embroidery and characterized by Vickers as “ancestral gestures.” A selection of these paintings, digitally enlarged and reproduced, was installed on the CAG’s windowed façade, the zigzag, linear and diamond patterns engaging high modernist tropes in dialogue with ages-old Indigenous forms and traditions.

Framed and mounted in grid formation on a white wall inside the gallery were 15 drawings in felt marker, created in 2009–10 in the mornings before Vickers left for what must have been an exhausting and discouraging day job. Part inspired mark-making, part conceptual project and part assertion of creative identity, these works, the exhibition guide tells us, “channel a range of persistent forms, including fire, grasses, hair, and bulrushes.” Built up of repeated, slightly wavy, vertical strands of colour, they compel us through their expressive energy and their unassailable beauty as well as through the ideas that drive them. Rather than critiquing or deconstructing modernist strategies, such as gestural abstraction, Vickers endows them with personal meaning and cultural consequence.

Charlene Vickers, installation view, Felt Ovoids, 2019–2021. Photo: Rachel Topham Photography.

Vickers’s ancestral gestures also extend to her three-dimensional work, with allusions to the cleansing ritual of smudging in the two mixed-media sculptures that compose Big Blue Smudge, created in 2021. (Although not mentioned as a reference, the two standing forms are also evocative of birchbark carry-alls.) Surface treatment here again marries aspects of modernist painting and mark-making to those of beading, braiding and sewing. Given the contrasts in scale of the various components, the former elements somewhat overwhelm the latter—to a curiously distancing degree. More immediately expressive is Diviners Grasses, excerpted from a 2010 installation by which Vickers mourned missing and murdered Indigenous women and consisting, here, of a row of 15 tall, thin, rod-shaped forms, leaning against a wall. Each form is composed of dried grasses and other organic materials (including human hair) wrapped in cotton cloth and thread and suggestive again of smudges— or perhaps highly abstracted and attenuated figures wrapped in bandages. In their slightly wobbly and repetitive verticality, they are the three-dimensional kin to the drawings displayed on the other side of the wall. They also symbolize what the exhibition brochure describes as “protection or healing” in the face of past and present violence against the most vulnerable members of an already marginalized and traumatized community. The cumulative effect of these emotionally charged forms, materials and metaphors is one of both power and sorrow.

A complex sense of cultural hybridity emanates from Vickers’s use of cedarwood in her sculptures and installations. The hand-carved cedar forms in both Diviners Spears and Cedar Bone Bead (for Faye HeavyShield) serve, in a way, as a grateful acknowledgement of her adopted place on Coast Salish lands where cedar has been, for untold ages, a foundational cultural material. However, the cedar boards of The Jingle House, an installation resembling the front of a small cabin and suggestive of a theatrical set or backdrop, resonate for Vickers with memories of her DIY dad and the cedar panelling in the Toronto home in which she was raised. The materials and objects located on and around both the front and back of this work include a selection of family heirlooms and gifts from friends, and range from tin jingles, braided yarn and Okanagan tea to folded camp blankets and a Wedgwood vase. Here, the material evidence of past and present, family and friends, settler culture and Indigenous culture contributes to a many-stranded condition of being in the world.

Faye HeavyShield, installation view of “New Work,” Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, September 17, 2021, to January 2, 2022. Photo: SITE Photography.

Painted in the cabin front’s “window” is the haunting image that drives this work: a woman’s profile face in nighttime silhouette, taken from a recurring dream of the artist. It strongly resembles Vickers’s own silhouetted face as seen in her 2011 digital short Wauzhushk Onigum, and, in the context of Jingle House, seems to speak to the search for an authentic self and, at the same time, the shadowy memory of a lost mother. (I see Vickers’s works as deeply thoughtful and, at the same time, intuitive. But what occurs when I bring my sensibilities to interpreting them? As David Garneau has written, the intuitions of art critics are “troubled by deep social attention, including prolonged communion with people whose lives are not reducible to our apprehension.”)

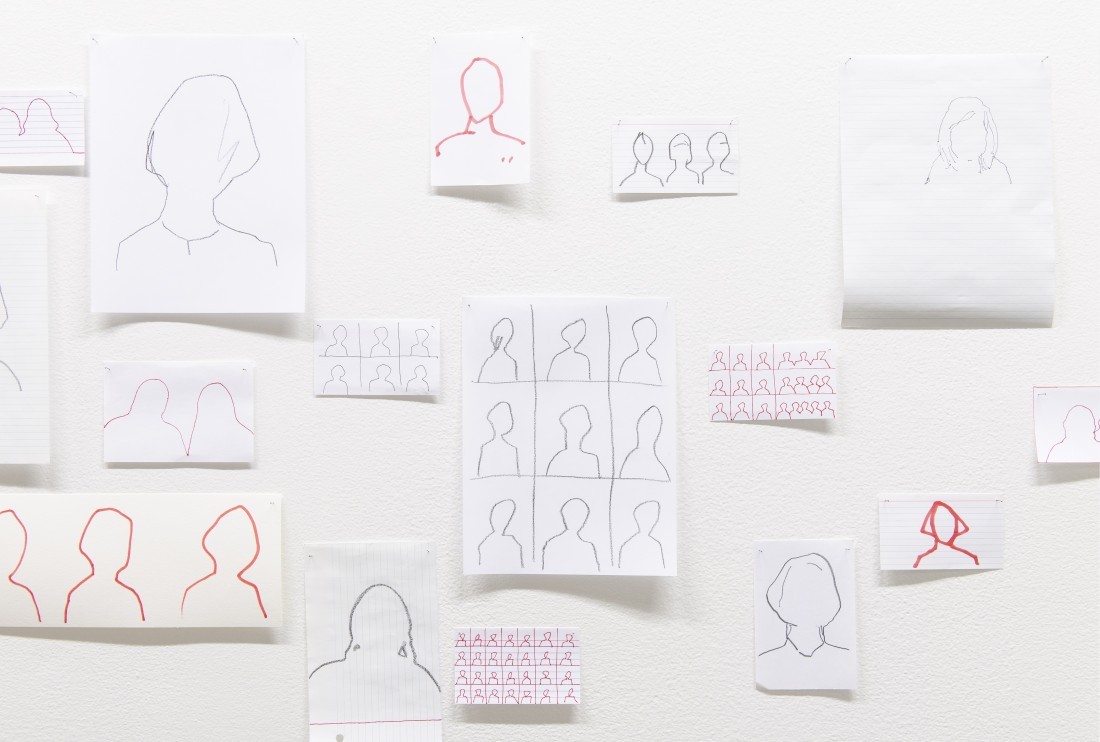

Faye HeavyShield’s grouping of some 50 unframed, mixed-media drawings, I’ll know you when I see you, also pivots upon a recurring yet elusive female image. Outlined sketches of a young girl’s head and shoulders, some with long hair in braids, others with short hair, all with facial features omitted, have been repeatedly rendered on inexpensive paper and index cards. Based, we’re told, on a photograph of the artist’s mother as a child, the images suggest a grasping after not simply memory and relationship but also fragments of a stolen identity. The short hair, especially, reminds us that the practice of cutting off the hair of Indigenous children at residential schools was one of the many punishing ways cultural identity was erased. The outlines of the silhouetted girl are like boundaries drawn on a map of loss.

Faye HeavyShield, the red line (detail), 2021. Photo: SITE Photography.

The mapping metaphor is more directly evoked by HeavyShield’s recent sculptural work the red line. The undulating beaded rope with its two conjoined loops is like a three-dimensional drawing of place or the linear elements of a topographical map, conjured out of body memories and placed on a platform-like plinth in the centre of the gallery. The labour-intensive process of fine beading this work represents is described in the exhibition brochure as “at once an introspective act and a generative one.” A member of the Kanai (Blood) Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy, HeavyShield grew up speaking Blackfoot on a reserve in southwestern Alberta, attended a Catholic residential school, studied art at the Alberta College of Art and took on self-directed studies of historical Blood beadwork in museum collections. She is acclaimed for investing her minimal forms with heavily weighted meanings and her red line is no exception: multivalent, it suggests Blackfoot beaded necklaces, Catholic rosaries, veins and arteries of bright red blood and, again, the landscape of her childhood with its hills, grasslands and winding rivers. Especially powerful is the evocation of the place where the Belly River flows into the Old Man River on the Blood reserve.

Faye HeavyShield, I’ll know you when I see you (detail), 2021. Photo: SITE Photography.

Although HeavyShield and Vickers grew up in widely different circumstances—one immersed in the culture, language and landscape of her birth family, the other separated from them—what brings these two artists together is the probing of memory, the richly metaphoric play of forms and materials and the assertion of identity through the turning, tumbling fragments of a perhaps unknowable past and a kaleidoscopic present. ❚

“Charlene Vickers: Ancestor Gesture” and “Faye HeavyShield: New Work” were exhibited at the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, from September 17, 2021, to January 2, 2022.

Robin Laurence is an independent writer, critic and curator, based in Vancouver. She has written essays, reviews and feature articles for local, national and international publications, and is a long-time contributing editor to Border Crossings. She is the 2021 winner of the Max Wyman Award for Critical Writing.