Ceal Floyer

There is a psychological phenomenon called belief perseverance that describes the persistence of one’s original conception despite the presentation of contradictory evidence. Although the latter abounds at the Ceal Floyer exhibition at DHC/ART, belief does indeed persevere. First impressions are particularly enduring, and illusion particularly inviting, so it is through careful positioning of these elements that Floyer, the choreographer, the producer, the poet-philosopher, creates narratives to which we willingly submit. Swayed by the charm of the final proposition, we knowingly attend to certain evidence and dismiss what doesn’t support our convictions.

The show’s curator, John Zeppetelli, describes Ceal Floyer’s art as “a heady interplay of title, referent, object, and apparatus of display”—the protagonists of the many mises en scene that comprise the exhibition—ones that read more Ionesco than Chekhov. Floyer positions each player so precisely and yet impossibly that one mocks the other—not derisively, but as in witty repartee.

Ceal Floyer, Light Switch, 1992–1999. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

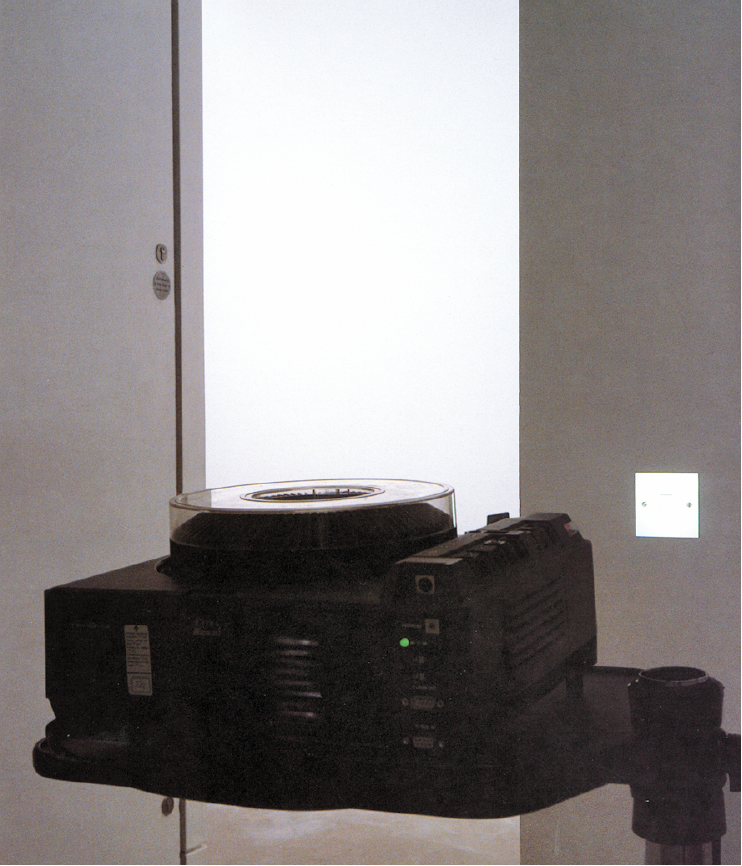

Light Switch, the opening piece (or “act”), quite literally sets the stage for the rest of the show. We see that a theatrical lexicon is indeed relevant to the work, and could be considered the container that holds it altogether. If lexicography is the skin of this animal, then pragmatics is the bones. Light Switch consists of an image of a light switch projected to scale on a wall, exactly where you would expect to find just such a thing. Directly in front of the switch, in plain view, is the projector, the source of the illusion and, conversely, the very thing that should dispel it.

Ceal Floyer accentuates the delightful sliver that divides belief from disbelief. In Door, a work consisting of light projected along the bottom of an actual door in situ, it is a slim horizontal band (a sliver) of light that divides belief from disbelief. It is a clearly deconstructed illusion and, yet, we so desperately want to believe in it. Even as we “puncture the impossible illusion,” as the artist calls it, by walking through the light cast by the projector, we find it difficult to accept the familiarity of that shadow and insist the momentary darkness was cast by someone passing on the other side of the door. With a small shard of generated light she presents a cue, a jumping off point, for the “leap of faith” that is required in believing. Borrowing, perhaps, here and in other places from the Theatre of the Absurd, she draws attention to otherwise inconsequential details that evoke sudden and even surprising curiosity, creating expanding narratives that take on a life of their own. Unprovoked, the imagined would have gone unimagined and a space laid waste for lack of form or content. Instead, enamoured by possibility, we fill more space with an entire imaginary narrative existing on the other side of the door—we are complicit in the illusion.

Floyer consistently works with themes of time and space, which are inherently “heavy’” subjects. However, by interrupting these otherwise daunting continua with light, she injects “lightness” in a sense of levity and brilliance. This sort of double entendre is, in fact, par for the course with Floyer, who revels in an obsessive play on words, one endless with possibility. Learning that the artist considers space as something concrete gives us a better understanding of her inclination to classify the majority of her works, even two-dimensional ones such as Ink on Paper, as sculptural. Furthermore, if space is concrete, then it can be shaped. And if space, like time, cannot be contained, it can at least be extended or diminished.

Ceal Floyer, Double Act, 2006. Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York.

Take, for example, 1-25, which projects the written numbers one to 25 (the number of images or impulses in a second of video) on the wall, each number allowed to rest for the number of seconds it represents. It is a self-portrait of time and of the medium itself. Moving forward (or up) to 25, the presence of each number increases in gentle escalation, rather than giving rise to crescendo, culminating, or never-ending in an absurdist anti-climax.

Overgrowth shows a slide projection of a bonsai tree enlarged to the size of a full-grown tree. Here we may be eager to read some deeper meaning of self-actualization, but as with most of the artist’s work, the answer is not buried but rests near the surface. In this case, Floyer explains Overgrowth as partially a response to the art institution’s obsession with things, its need to fill a space. To make a large piece, all that is necessary is to move the projector back. This is illusion without trickery, this is illusion wearing language as its intentionally clumsy disguise; and aware of its genuine untruth, it undermines itself. It is a self-deprecating kind of illusion. This is the kind of trickery that we can feel comfortable with, it is not slick or perfect—it is an unspecial effect that, by default, would be just effect. Furthermore, we see that when we are willing to attend to it, the conversation of cause and effect is noteworthy, and even humorous. To this end, Floyer, a self-proclaimed “slap-stick conceptualist,” concedes to the sacrifice of showing work that involves humour in an institutional context, understanding that some of the joke may be lost due to demographics and our compulsion to take art seriously. “There is nothing worse,” she says, “than to have to tell someone when something is funny.” ❚

“Ceal Floyer” was curated by John Zeppetelli and exhibited at DHC/ART Foundation for Contemporary Art in Montreal from February 16 to May 16, 2011.

Tracy Valcourt lives and writes in Montreal