“Caught in the Act: The Viewer as Performer”

“Caught in the Act: The Viewer as Performer,” an all-Canadian contemporary exhibition at the National Gallery in Ottawa, rides a global wave of museum shows and art festivals that have variously been called participatory, interactive, performative, experiential or relational. It is concurrent with “theanyspacewhatever” at the Guggenheim—which includes the usual suspects, such as Rirkrit Tiravanija and Maurizio Cattelan—and with Christoph Büchel’s “Deutsche Grammatik,” an exhibition that converts the hallowed galleries of Kassel’s Fridericianum into such everyday spaces as a gym, supermarket and conference room.

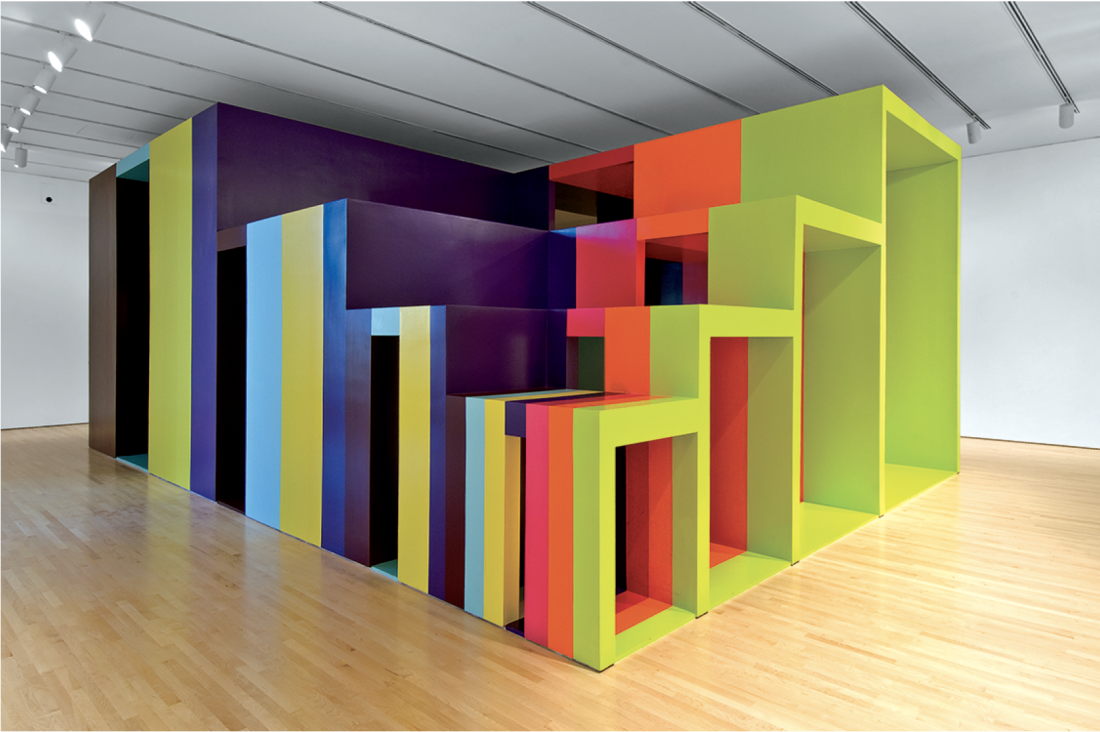

Rodney LaTourelle, Model for Inner Expansion, 2008, wood, drywall, acrylic paint, hardware, 9.8 x 6.7 x 3.8 m. Installation view, National Gallery of Canada. Photo: Terry Brennan. Courtesy the artist.

There is, of course, nothing new in artistic efforts to overcome the alleged gap between the viewer as passive observer and the artwork as an autonomous, fixed object. The various strategies employed in “Caught in the Act”—transformation of architectural space, electrically charged objects that react to the viewers’ presence, and installations that foreground the communal aspects of art making—have a long history that can be traced back to Marcel Duchamp, Dada, Allan Kaprow’s happenings and the Fluxus movement, to name but a few of their antecedents. In the NGC’s exhibition, curator Josée Drouin-Brisebois has emphasized the continuity of experiential art by including works from the ’70s, ’80s and early ’90s (by Mowry Baden, Jana Sterbak, Max Dean and Rebecca Belmore). These older works present, as she writes in the catalogue, a framework for the “new practices” of BGL (Jasmin Bilodeau, Sébastien Giguère and Nicolas Laverdière), Geoffrey Farmer, Massimo Guerrera, Glen Johnson, Rodney LaTourelle, Jennifer Marman and Daniel Borins, and Kent Monkman. Discovering connections among the works of different periods provides an added interest to this lively exhibition.

In the gallery’s large, glassed hall, Belmore’s monumental wooden megaphone invites visitors to address Parliament (the grand buildings can be seen through the window). Ayumee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to their Mother, 1991, was built as a response to the Oka crisis, a political gesture that suggests that the earth itself should be addressed in territorial disputes. The megaphone travelled to numerous First Nations communities where it functioned as a prop in events that had real political bearing. This in contrast to another microphone in the exhibition, mounted by Marman and Borins on a presidential podium that sports the face of Buck Rogers’s Dr. Theopolis on its front. Its political relevance is irony only; when a visitor dares to use it, the words are scrambled as soon as they are spoken. Marman and Borins’s various installations include a huge yellow ribbon, hanging somewhat forlornly on the wall, its points sliding onto the floor. They question the stability of signs that travel through a myriad of cultural incarnations. What is signalled unambiguously, however, is the presence of the viewer; Presence Meter, 2003, is a minimalist-looking panel with hundreds of ultrasonic sensors that wave all their little needles whenever you approach it.

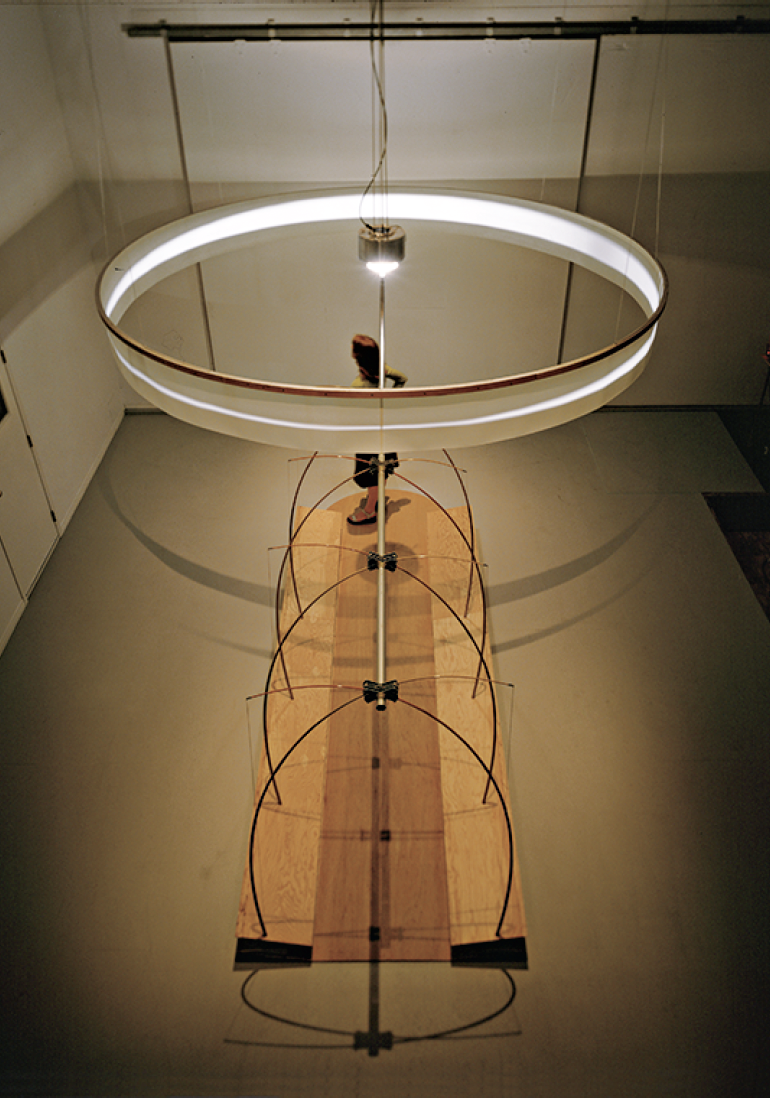

Mowry Baden, The Light that Severs Day from Night, 2003, stainless steel, plastic, aluminium, 262 x 450 x 567 cm. Courtesy Diaz Contemporary, Toronto. Collection of the artist.

While it is hard to say whether Presence Meter is glad to see you, Jana Sterbak’s 1984–85 wire figure with electrical coils turns red hot when you approach it, provoking intense emotions of attraction and fear. There’s a more subtle sense of danger in Mowry Baden’s Vancouver Room, a re-created 1973 installation of a tilted room that skews the viewers’ perception to the point of creating dizziness. In another installation, this one from 2003, the viewers’ equilibrium is restored by a walk under a moving halo of light that creates the natural rhythm of night and day. Baden’s interest in the embodied, sensual experience of space is echoed in the work of the much younger Rodney LaTourelle. His Model for Inner Expansion consists of geometric, brightly coloured spaces in increasing sizes that fill the room and frame the viewers who walk through them. It is like stepping into a painting, experiencing its colour, light and space through the body rather than the eyes only.

While those of LaTourelle and Baden focus on individual perception, the installations by Monkman and Guerrera draw out the socializing potential of gallery spaces, albeit in very different ways. Monkman’s teepee, so tall that it appears to penetrate the ceiling, is turned into a decadent boudoir, complete with a Victorian divan and sofas from which to watch a hilarious “documentary,” Shooting Geronimo, 2007. The sense of dalliance and seclusion that prevails in Monkman’s Boudoir de Berdashe contrasts with Guerrera’s open, light-filled gallery. The space is transformed into the artist’s active workspace and shows a collaborative project that has been ongoing since 2000. Guerrera works with people and is physically present in the space at least one evening a week when he sits down with visitors for a conversation, listens to music and shares some fruit. Plants grown from the pits of these fruits are displayed in the room along with drawings, photos, and a range of uncanny sculpted objects that often resemble, but never faithfully reproduce, parts of the body.

Rebecca Belmore, Ayumeeaawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother, 1991, plywood, fiberglass resin, leather, plastic loudhailer; includes archival images, audio reel, support structure, 256 x 206 cm. Collection of the Walter Phillips Gallery, The Banff Centre, Banff. Photo: Monte Greenshields.

In the mid ’90s, Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term “relational aesthetics” for works like Guerrera’s that aim to recreate a sense of connection between people and things through everyday interactions in the gallery. Bourriaud connects the rise of relational art to the Internet’s opening up of new ideas of community. Undoubtedly, as the ultimate tool for interactivity, the internet has changed our sense of space and community, a change that has worked its way into contemporary installations and performances. “Caught in the Act” acknowledges the role of the Internet by including Glen Johnson’s (very funny) website “Persiflage” (www.persiflage.ca). The website will have far more viewers than any of the other artworks, but the work’s presence in the actual space as an ordinary computer is modest. The curatorial decision to downplay new media underlines the sense of continuity that prevails in this exhibition. Despite the sudden rise of the internet, an underlying commonality links not only the installations from the last decennial that are shown here but extends to all of Modernism. What is shared in common is a desire to upset the autonomy of the static artwork, with its false claim to a fixed reality.

Max Dean, with technical help from Raffaello D’Andrea, takes this mission to a literal, humorous extreme: a plain table in an empty room startles unsuspecting viewers by sliding towards them, following them around like a puppy. Technology and theatrics have greatly increased modern and postmodern art’s potential to reveal the world’s endless contingencies. But even theatre was once considered too static, too limited to naturalistic representation. Antonin Artaud railed against the fixity of the written text and called for a “theatre of cruelty” to eradicate a false reality that, he wrote, “lies like a shroud over our perceptions.” Geoffrey Farmer, always the historian, titled his installation Theatre of Cruelty. A small “theatre” is surrounded by framed photographs and found objects such as masks and spears that relate to the theatre as well as to natural disasters and war. Inside, more objects take on a life of their own in a play of lights and sounds that turn on and off, constantly altering the mood of the room and the meanings of its immobile objects.

Massimo Guerrera, Darboral (Here and now, with the impermanence of our remnants, 2002, colour photograph. Courtesy Galerie Joyca Yahouda, Montreal and Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto.

Fixed meanings are always absent in the work of BGL as well. Much of the rascally trio’s work, mostly props from past performances, has found a home in the museum for some time now, on metal storage shelves, along with buckets, brooms and ladders, and a real stuffed dog. The only artists ever to use the National Gallery for storage space, BGL rewards curious visitors with magical spaces hidden behind their bric-a-brac. Especially timely is another of their works, Artistique Feeling II, 2008. A Genie lift rises high in one of the museum’s tallest glassed spaces. It seems ready for a window cleaner but, instead, spews banknotes of different denominations. It may be a reminder that the market continues to assign to artworks the most static of meanings—a trading commodity. But the viewers who delight in the ballet of the downward spiralling bills and the dance of the guards catching stray ones are reassured by people’s ingenuity and playfulness in turning things around. ❚

“Caught in the Act: The Viewer as Performer” was exhibited at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa from October 17, 2008, to February 15, 2009.

Petra Halkes is a painter and critic living in Ottawa.