Cartographies of Desire

Cultural institutions are often seen as intellectual cocoons, or worse, as ivory towers in which the vicissitudes of physical reality are transcended or even ignored. Rarely has this notion been more seriously challenged than in the recent exhibitions of two of Canada’s leading visual artists, Eleanor Bond and Irene F. Whittome, at Saskatoon’s Mendel Art Gallery. Both artists share a deep concern for the ways in which we struggle to make sense of, and move through, the inner and outer places of being. They are cartographers of desire, mapping out not only society’s failure to understand and ameliorate the complex landscapes we inhabit, but its potential to mine these spaces, uncovering the gems of well-being buried beneath the elaborate surfaces of existence. While Bond’s utopian vision scrutinizes the external locations we inhabit and strives to find solutions to the often brutal exigencies of urban life, Whittome casts her eye inwards. By inverting the colonizing gaze of ethnography and anthropology, she reveals a sense of liberation borne of the struggle to own one’s inner, personal landscape.

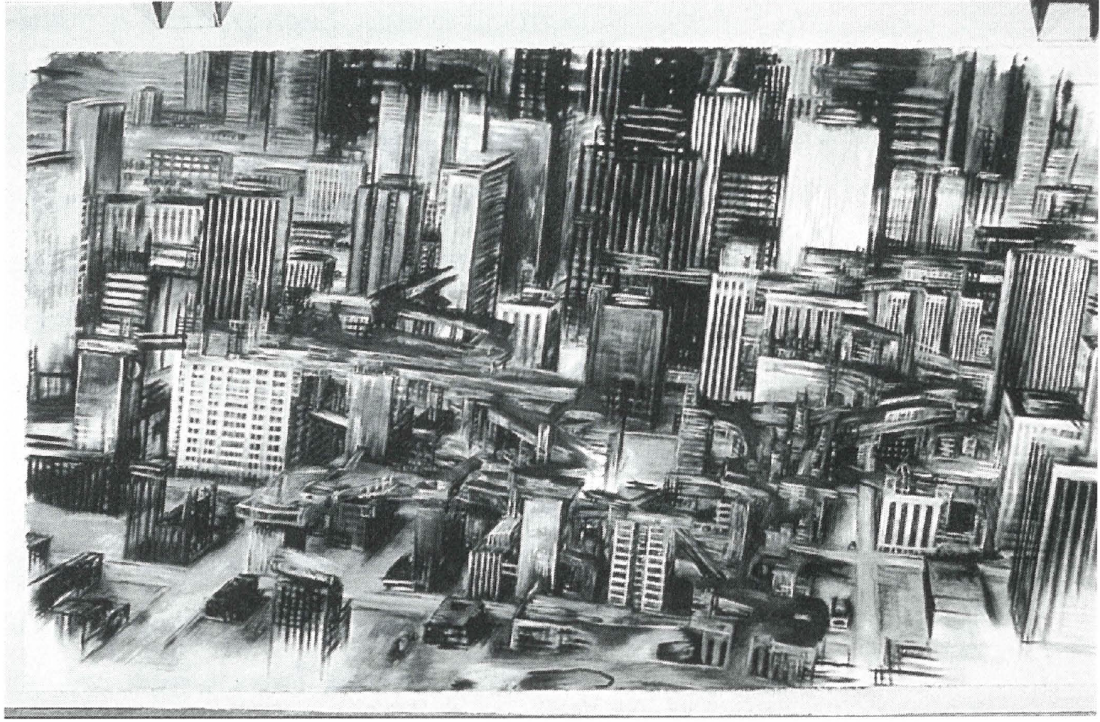

In the six paintings on display at the Mendel (including her recent work done as a guest artist in Rotterdam) Bond’s playful imagination whisks the viewer through bustling metropolises, underground cities, regenerated greenhouse harbours, fish-shaped lakes and communities in the clouds. All the while her signature over-blown colours and vertiginous perspectives place the viewer in an uncomfortable state of wonder. My immediate reaction to these paintings is to stand in awe at their naïve hopefulness. Yet amidst these sci-fi dioramas lurks something threatening.

Irene F. Whittome, Creativity: Fertility, detail, 1985, oil and crayon on paper, 206 x 410 cm, each element 51 x 41 cm. Photograph: Denis Farley. Courtesy: Musée d’art contemporain.

Her paintings are huge, brightly coloured affairs, depicting strange moments wherein the trajectories of art and science intersect. Concerned with the realities of social dislocation, unemployment, housing shortages and ghettoization, Bond articulates visions of the way things “could be.” In the face of increasing anxiety brought on by a perceived inability to control technology (a situation aggravated by a peculiar and deeply felt millennial angst) Bond’s landscapes offer an architectural reprieve. But in her capacity to imagine utilizing technology for the preservation of social and environmental good, there dwells an equally poignant testimony to how dismally we have failed.

Take, for example, her painting called An Endless City: Cozy Living for a Large Population. It depicts a huge mushroom-like building flanked by a Tatlin-inspired tower, buildings that provide creative housing for hundreds of thousands of occupants. In content and form this painting bears striking resemblance to Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. Within this painting she creates a vision of an earthly paradise alongside an ever-present subterranean threat of hell. Unlike Bosch, however, Bond’s hell is not some distant netherworld reserved for the wayward sinner; it is the present reality of welfare, homelessness and urban decay.

It’s in this articulation of duality that Bond’s work forges interesting connections to Irene F. Whittome. Whittome is a collector of things. Her menagerie of codified and catalogued items illustrates an impulse for structure in the face of the unknown; this structuring speaks to a desire to impose “order” on a seemingly barbaric and hostile environment through whatever means necessary. Yet in her constructions of the archive or museum Whittome is able to play with the gaze, irrevocably bending and transmuting it from surveillance into insight.

Eleanor Bond, Endless City: Cozy Living for a Densely Populated Region, 1997, detail, oil on canvas, 250 x 442 cm. Collection: The Artist. Photographs Sheila Spence. Courtesy: Musée d ‘art contemporain.

Entering Whittome’s exhibit, the viewer first encounters Èmanation=Le Musée noir, a series of objects—some on the floor, others suspended in cotton in black leather frames, others embedded in deep, black encaustic. I felt as though at any minute I might be greeted by a Conradian figure complete with a notepad and calipers to measure the thickness of my head. “I always ask leave in the interests of science, to measure the crania of those going out there,” he’d say as he had in Heart of Darkness. It is the desire to catalogue the abysmal that lurks behind these articles of an archival imaginary, this decapitated turtle, these masks, or safety pins, or manuals.

But it is also within these archaeological assemblages that Whittome turns the gaze on herself. With an almost brutal objectivity—one that throws into commotion the seemingly transparent and benign tenets of scientific disinterestedness—Whittome lays bare the twisting recesses and territories of her own inner landscape. It is in this inward, almost frighteningly objective vision and its mimicry of conquest that Whittome depicts both the lamentable failure of our dealings with psychological and spiritual environments, and the freedom discovered in the ownership of ones own body and space. Her brilliant series of drawings “Creativity; Fertility” (1985) like the sketches of an explorer, loosely illustrate female and male genitalia—those areas of imagination and memory that have proven so elusive, fleeting and unmanageable. In various stages of symbiosis it’s as though the archival and cataloguing principles of anthropology and ethnography allow Whittome to map the outer regions of her own creative impulse. Not unlike the so-called discovery of Lake Victoria, Whittome’s series of 40 drawings ring with the triumphal gesture of a personal discovery that has logged and diagrammed its way back to the source.

Both Eleanor Bond and Irene F. Whittome are artists who have stripped away the vestiges of artifice and pedantry from their respective mediums to reveal a strongly articulated vision of regeneration. As I left the cocoon-world of the gallery to walk back into the landscapes of my own existence I did so with renewed confidence. For while the places I inhabit seem almost mercilessly flawed, they nevertheless contain within them the germs of, dare I say it, utopia? ♦

The Irene F Whittome and Eleanor Bond exhibitions were at the Mendel Art Gallery from January 15, 1999 to March 7, 1999.

Sky Glabush is a painter and writer living in Saskatoon.

Eleanor Bond, Elevated Living in a Community-Built Neighborhood, 1998. This and work on previous page from series “Some Cities,” 1997-1998. Courtesy: Musée d’art contemporain.