Caroline Mousseau

Caroline Mousseau’s recent show “Wrestling with Static ” at Winnipeg’s rejuvenated artist-run centre aceartinc. requires serious scrutiny. The perennial problem of keeping a viewer looking longer never goes away, and every painter has found ways of dealing with the complex issues related to the how’s and when’s of their imagery. The speed of dissemination and duration of a viewer’s engagement lie within the methodology and facture of the artist. The complexity of a simple situation seems to be at the core of Mousseau’s painting practice.

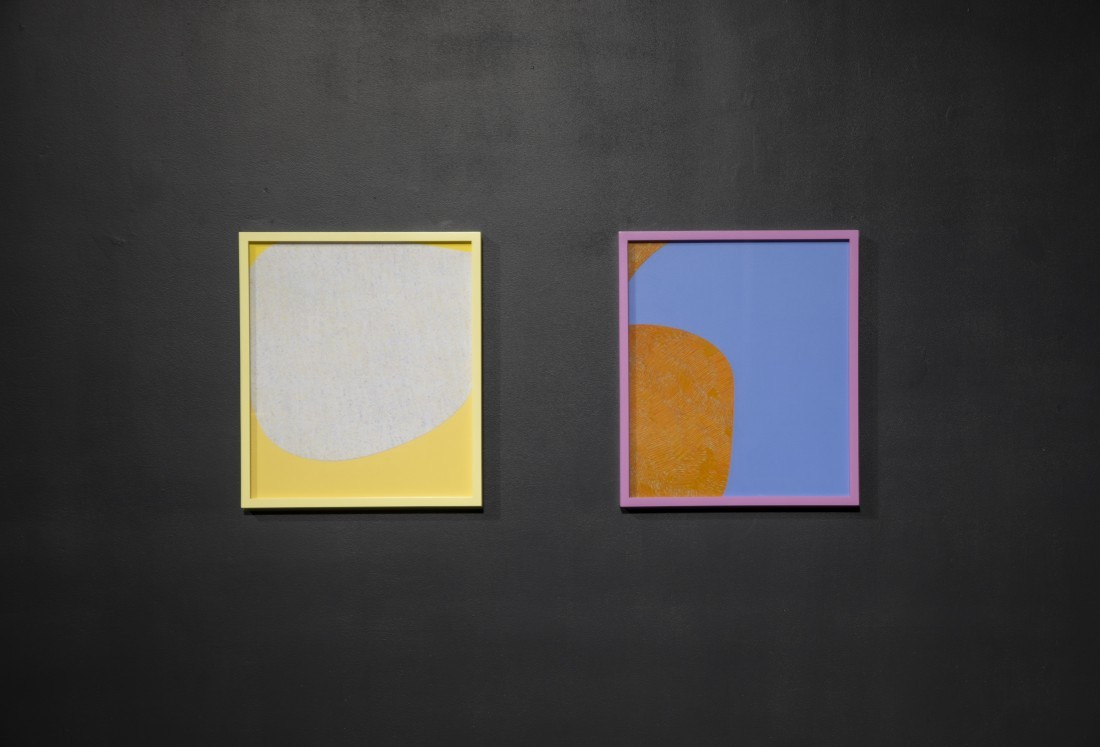

Various strategies are employed in the exhibit that encourage you to explore the extremities of looking. There are eight works in the show, which allows Mousseau to get immediately, yet patiently, to her point. Seven smaller, colourfully framed works consisting of oil and oil pastel on paper are quirky and contain forms and fields that are alternately truncated or surreptitiously cropped, while the large two-panel painting is chromatically intense and self-assertive.

Caroline Mousseau, installation view, “Wrestling with Static,” 2024, aceartinc., Winnipeg. Photo: Sarah Fuller. Courtesy the artist. Left to right: Untitled (2023), oil pastel and oil on Arches paper framed in latex-painted maple, 99% UV conservation-grade clear glass, 48.3 × 41.9 centimetres; Untitled (2023), oil pastel and oil on Arches paper framed in latex-painted maple, 99% UV conservation-grade clear glass, 48.5 × 42.2 centimetres.

Slowness, of course, is more than welcome and perhaps the only real way to proceed if the viewer wants to get something more substantial from these images. And even as the structures in the paper works seem shyer or softer, their frames often present a more eager-to-chat demeanour.

The large two-panel work consists of three colours: bright pink near fluorescent, oxblood, maybe, and the skin of a satsuma. The easiest way to navigate this image is to be super-literal about what you see before you. Clearly delineated handcrafted lines of equal width could represent, literally, brush strokes; a meta-painting of, you guessed it, meticulously controlled brush strokes. After closer inspection I can tell you that the fictional brush used on the left-hand panel has seven bristles/hairs while the brush used on the right panel has a width of 18 bristles. This odd couple of brushes appear busy navigating their own rectangular expanses in either a more or less orderly way, perhaps even in some sort of dialogue with each other.

All of the works are hung slightly low, allowing the viewer to get up really close and nose their way around. I wondered if Mousseau may be using a certain brand of modernist abstraction as a foil, playing on our prejudices about works that seem to be made up of few elements, a kind of formal gesture as cul-de-sac. This perceived ploy of needling the viewer might be to get us emotionally involved and thereby examine more closely what is on offer. Certainly, the rich colour hints at big emotions, but I suppose Design, a benignly apposite strategy, is also possible. Hard-to-notice moments of collage and evidence of taped or stencilled edges reveal themselves eventually. You begin to navigate through the subtle shifts that could make this work more personal. The lackadaisical criss-crossed build-ups of pastel-hued oil crayons on the paper works create the only thing possibly related to some kind of impressionistic optical colour mixing, suggesting a rendered world containing gravity and air. But it refuses this notion as adamantly as it teases us. A slow accretion of undulating marks of repeated curving lines coalesces. In some areas the pastel has been incised, or sometimes entirely removed to reveal another colour, creating a whole other layer of specificity, at once haptic as well as optical. That being said, the forensic scrutiny asked of us also allows each coloured line to remain intrinsically itself, removed, even amongst its easy, loopy, scribbled networks.

Caroline Mousseau, Untitled, 2024 , oil on canvas, 152.4 × 274.3 centimetres. Photo: Sarah Fuller. Courtesy the artist.

The paintings go about their business with a sort of embodied indifference, leaving you tracking an environment of abundant absence. You become responsible for the static within your own mind.

Other tricks of engagement might tempt the magpies among us. The framed works all have highly reflective UV glass that adds another somewhat phenomenological dimension. The resulting glare forces us to resort to close looking, otherwise they prove too difficult to see. The best way to look at these pictures is to be so close to them that your own body would block the glare of incoming sunlight. For this reason, as well as the pond-like motifs depicted, I was tempted to think of them as little fragments of landscape. The outside world entered into the sacrosanct modernist rectangle not by the back door but, instead, by the front window.

Objectification seems important; every detail is separated out and examined with care until we move on to the next separate detail and then the next. The question becomes: What does this all add up to, what is the experience of these paintings? Why are we groping at colours, groping at shapes, groping at surfaces and processes? Perhaps the essence of this activity is coming to no final conclusion about these accumulated experiential titbits. Perhaps ambiguity is precisely the point, forcing us to take joy in not knowing. We enact the leap of faith that abstraction provides us, the stark value of just being in the here and now, all the while doing what comes naturally to many human beings—looking and thinking simultaneously.

Things resist being named. Mousseau seems to try hard to avoid any associative linkages within the works on display. Keeping language outside of painting seems crucial. In this way the works may seem cold or distanced as they reject our world of day-to-day appearances. But the artist highlights the ways in which we approach and delineate these daily interactions. Even her colour, in all of its finely calibrated nuance, vibrates with its own intensity but also avoids being linked to life; it behaves like something separated out from the world. I found myself floundering to name colours in ways that were much too vague—hot pink, or in overly nerdy/diaristic ways that only made me feel implicated in the naming process—gorse yellow or marigold petal, or that indescribable colour in the middle of a mushy banana.

Caroline Mousseau, installation view, “Wrestling with Static,” 2024, aceartinc., Winnipeg. Photo: Sarah Fuller. Courtesy the artist.

When Mousseau has talked about her process, she says she chooses her colours almost arbitrarily and then creates a palette, being careful to check or correct the paint mixture’s value and fine-tune each colour to be of equal tonality. She does this via grey-scale technology with a computer. The use of photography to aid in the creation of these works might be a big surprise for some but make no difference to others. Although you do wonder how different the paintings might be without this fastidious tonal tinkering, I believe that this colour equality results in a certain conceptual equivocation; and again, equivocation might be the point.

Back to that pesky title “Wrestling with Static.” Static: Lacking in movement, action, or change, especially in a way viewed as undesirable or uninteresting. In physics static is concerned with bodies at rest or forces in equilibrium, or, put another way, when something is acting as weight but not moving.

Relate these definitions to the works and their ways of being as literally as you want, but of the utmost importance, I think, is to keep on grappling with what is actually there in front of you, in real time. Mousseau allows us to feel empowerment in our own attempts at empiricism. ❚

“Wrestling with Static” was exhibited at aceartinc., Winnipeg, from March 8, 2024, to April 19, 2024.

Craig Love is a painter. He lives and works in Winnipeg.