Carolee Schneemann

A recent survey of work by American artist Carolee Schneemann depicts both the pleasures and costs of an early decision to foreground the body, always politicized, over five decades of production and as many genres. Perhaps best known for key performances such as Meat Joy, 1964, an orgasmic celebration of materiality in which she and others roll about in paint, fish and chicken parts, newspapers and more, Schneemann also made paintings, installations, film and video, and photographs, and it’s this largesse of production that the survey brings neatly into focus.

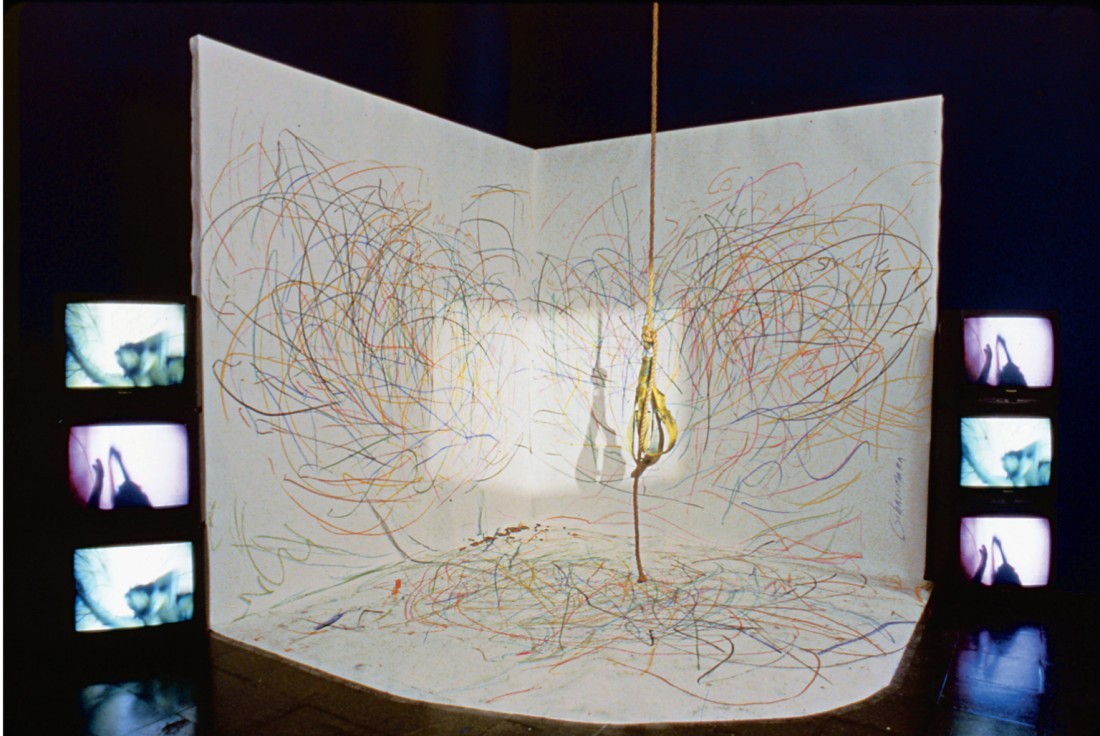

Carolee Schneemann, installation view of Up To And Including Her Limits, 1973–76, crayon on paper, rope, harness, video, monitors and players, Super 8 film projector. Courtesy the artist and Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, New Paltz, NY.

A remarkable series of watercolours, for instance, entitled “Partitions,” 1962–1963, evokes multiple narratives in feminist art and performance. Never before shown in its entirety, and years later still in the private collection of the artist, these six small paintings are accompanied by a short descriptive text and describe a performance—never realized—for the Feigen-Herbert Gallery in New York. In muted colours and lush, broken lines, the paintings show figures stepping out from abstract forms—the shelves and partitions envisioned for the event. Here, bodies literally step out from a frame, a graphic rendering perhaps of Schneemann’s own term for the performance work: “exploded canvases.” The exhibition doesn’t say why the show never happened, but the works on view throughout the exhibition offer considerable perspective: performance is hard. And bodies are messy, politically volatile and at once expensive and unmarketable.

Carolee Schneemann, Hand/Heart for Ana Mendieta, 1986, C-prints, acrylic paint, chalk, ashes on paper. Courtesy the artist and Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, New Paltz, NY.

Brian Wallace has curated a pleasantly meandering exhibition that includes over 70 works and makes a number of useful points. First, Schneemann’s early work in painting is at once unique and very much of its time. Early paintings in the tradition of abstract impressionism, such as Sir Henry Francis Taylor, 1961, seem to lean out into space via thick brush strokes and collage elements that move towards sculpture. Then painting-constructions such as the hinged box entitled For Yvonne Rainer’s Ordinary Dance, 1962, plainly holler “agency” in the wrought feel of added mirror and glass and the charred colouring of the box that has been intentionally set on fire. Later, the paintings take on kinesthetic aspects, as in the superfine Fur Wheel, 1962, in which fur, tin cans and oil paint affixed to a motorized lamp base seem to comment on the avant-garde and domestic play, at once recalling Oppenheim’s fur cup or a defaced Davy Crockett hat. These works find a young Schneemann grappling with art history, and they prefigure her move to performance. Equally, they evoke Jackson Pollock’s action paintings and Robert Rauschenberg’s combines and recall the fast rise of so many of her contemporaries and the fierce marketability of modern painting’s newest aesthetic.

Safer choices, apparently, were not the point. Schneemann continued to embrace formal concerns about the “how” of art, but political content began shaping the work increasingly. Over the next four decades, the body as object and subject invoked domestic power struggles and headline news, with tone varying from anger, humour to melancholy. The silkscreen The Men Cooperate, 1973, with its collaged photo elements, documents the mundane choreography of shared work, as one lover moves out and another moves in. In War Mop, 1983, a motorized kitchen mop affixed to a Plexiglas stand rhythmically wacks the top of a tv monitor playing her video Souvenir of Lebanon, with its slow pan of bombed-out villages in Lebanon and Palestine. In Terminal Velocity, 2001, photographs of seven different people falling from the World Trade Towers on September 11 appear side by side and are magnified in sequence down the frame; the illusion suggests their increasing proximity to the viewer, but the consistency of their posture has the effect of freezing time.

Carolee Schneemann, installation view of War Mop, 1983, mop, Plexiglas, motor, video, monitor, player. Courtesy the artist and Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art, New Paltz, NY.

An expansive vision of feminism is operative here. If her early work reimagined the tradition of the female nude by means of performance that allowed her to be, in her own words, “both image and image-maker,” the later work shows the artist making the political personal through an army of techniques that attempt to bring the body into closer reach. In a radio interview, Schneemann recalled, “It took many years for the work to have a context around it, and that context came from feminist principles in the ‘70s.” But the aesthetic remains for me oddly, and happily, out of step. For instance, the silver gelatin print Portrait Partials, 1970/2007, is almost unbearably close at a moment when knowing distance—from terrible wars and terrible war crimes—is the norm. Detailed, beautiful in composition, the image arranges multiple close-ups of mainly orifices (nostrils, eyes, mouths, navels, vaginas, anuses) on a tidy grid. Elsewhere, in Vesper’s Pool, 2000, photos, diary notes, and natural and domestic objects tell the story of the death of the artist’s cat. Here, too, in the deadpan presence of, say, a bloodstained nightgown, there is a compression of life that feels weighted, even claustrophobic. This work resists glamour or irony. Here’s life, it says. Here are the bodies. And maybe no “context” ever quite readies us for either. ❚

“Carolee Schneemann: Within and Beyond the Premises” was exhibited at Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art in New Paltz, ny, from February 6 to July 25, 2010.

M J Thompson is a writer living in Brooklyn and Montreal.