Carolee Schneemann and Stan Brakhage

Presentation House Gallery (PHG) in North Vancouver is a physically unprepossessing space: three modestly made over rooms on the third floor of what was once somebody’s home. Still, those old rooms have hosted an astonishing array of historical and contemporary exhibitions of photo-based art. Recently, PHG undertook the brilliant pairing of shows by pioneering performance and multi-media artist Carolee Schneemann, who divides her time between Montreal and the New York countryside, and experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage, who died in Victoria in 2003.

Friends and colleagues since the late 1950s in New York, they profoundly informed each other’s creative thinking. Also deeply involved in the interchange of influence and innovation was musician/composer James Tenney, Schneemann’s then-partner and Brakhage’s close friend. While in Vancouver for the installation and opening of her 2003 video work DEVOUR, Schneemann delivered two eloquent and melancholy public talks, describing mutual inspirations and cross-fertilizations and using evocative terms such as “reciprocal interactions” and “wishful coherence.” “We had an irrefutable but also blind belief in the potential to transform media,” she said.

Schneemann also spoke about complementary explorations of concepts of space and time and the ways in which each discipline might lay claim to them. Apart from influencing each other, all three artists have greatly enriched the recent history of art, music and film, laying the foundations for succeeding decades of experimentation and interdisciplinarity. Still, Schneemann cautioned her audience not to romanticize their revolutionary lives and times. While indeed transforming their chosen media, these artists struggled with conflicting beliefs and “contentious and disturbing issues,” along with extreme poverty and its accompanying stresses.

Connections were evident between Schneemann’s early work, as an expressionist painter of landscapes and the human figure, and her subsequent explorations of alternative art forms. “I’m still a painter,” she asserted, arguing that painting’s dynamics could be realized not simply with a brush and pigment on canvas but also with a body or a camera or a set of forms and projections moving in space. “Painting might include yourself in a force field,” she said in a documentary film, Imaging Her Erotics, which was screened at her first talk, then added, “I have to put my body where my thoughts are.” As with her earliest art, Schneemann continues to find her creative and philosophical register in the natural world. Tropes of landscape, figuration and animal life, cats especially, recur throughout her work.

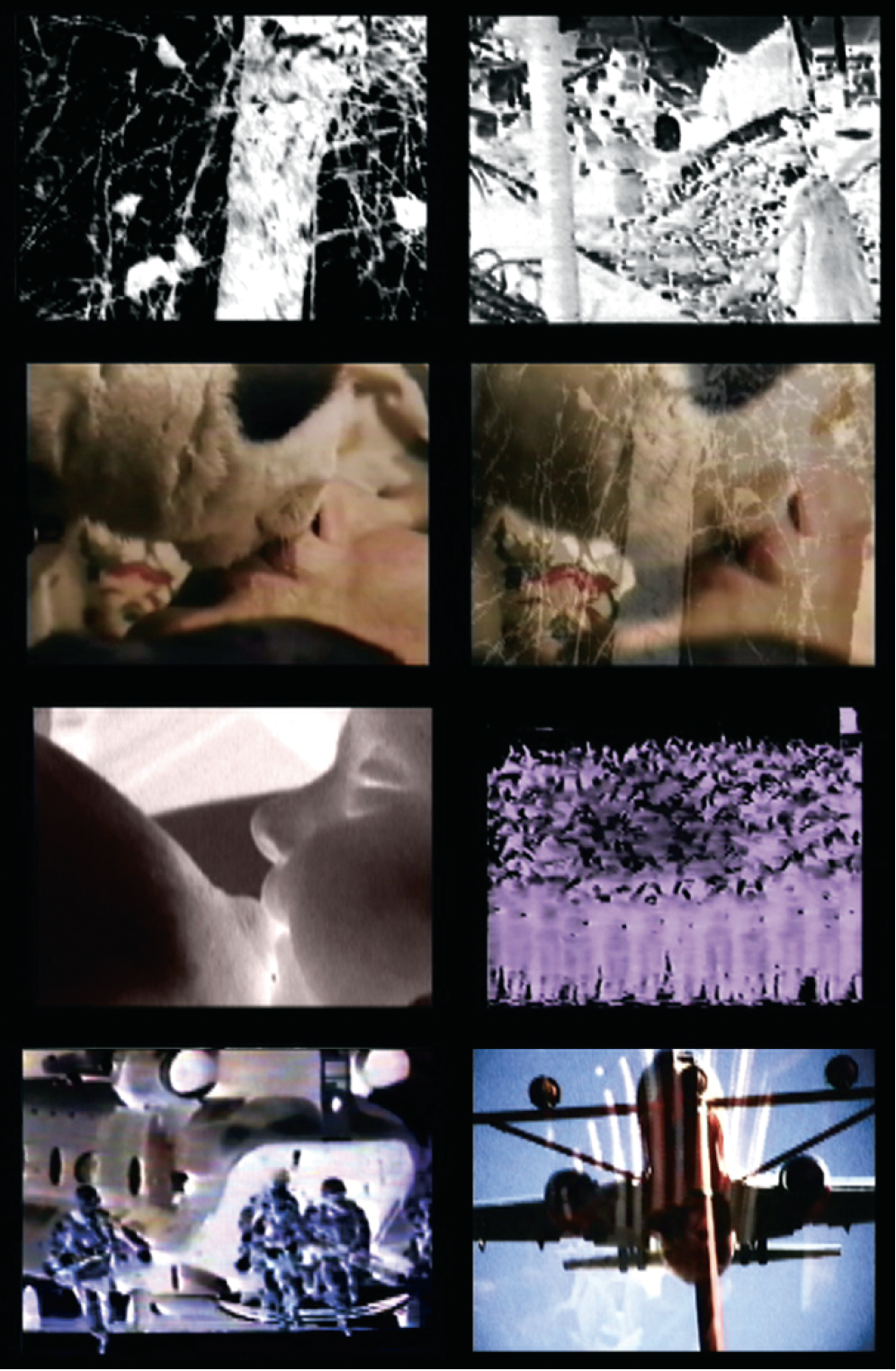

Carolee Schneemann, video stills from DEVOUR, 2003, dual-channel video projection. Courtesy Presentation House Gallery, Vancouver.

In the 1960s and ’70s, Schneemann created a number of provocative performances, two of which are now regarded as iconic. One is Interior Scroll in which, naked and paint-daubed, she read a moving and highly personal poem about gender inequality, printed on a long, narrow scroll of white paper, which she unfurled like a literary tampon from her vagina. The other is Meat Joy, in which she and a group of male and female colleagues, clad in bathing suits, danced, cavorted and rolled around on the floor with raw meat and fish, red and black paint, heaps of cheap paper and, perhaps most importantly, each other. Orgiastic as it initially seemed, this work was “not about fucking,” she said, “but about lost pleasurable expressivity” between women and men.

Schneemann’s performances initiated charged dialogues about social repression, cultural taboos and longstanding fears of female sexuality and power. They were also calls for liberation— of both women and sex. Her early films, too, took a feminist position of focussing on “lived experience” and the daily shapes, forms and dispositions of the domestic realm. These unmasculine and unheroic subjects were, she asserted, just as worthy of an artist’s close examination as those traditionally sanctioned by the male establishment. Also worthy—and part of her counterculture ethos—were anti-war feelings provoked by the prolonged, hideous war in Vietnam.

The significance here of Schneemann’s early production is that it still has the power to outrage and empower its viewers and that its images and intentions resonate in DEVOUR. The events and consequences of September 11th, the US-led occupation of Iraq and the religious Right’s advocacy of war while proscribing huffily against sex, nudity and a woman’s right to choose what happens to her own body all seem to have fuelled her contemporary creative expression. A wall-sized, dual-screen video projection with two smaller, adjacent monitors, DEVOUR montages images of violence and disaster with those of domestic pleasures, daily intimacies and the natural world.

Using edited clips of news footage gathered from Lebanon, Haiti, Mexico, Ecuador, Sarajevo and Kansas City, along with videotapes she shot in New York and Maine, Schneemann has structured this work to (in her own words) “contrast evanescent, fragile elements with violent, concussive, speeding fragments, political disasters, domestic intimacy, and ambiguous threats.” All play against an arresting track of found sound, some of it dragged from its corresponding visuals into the following frames.

The work includes altered, tinted and distorted imagery of car crashes, burning buildings, sniper attacks, armed soldiers leaping from a military helicopter and a wounded man dragging himself across pavement towards some form of shelter. Most disturbing is guerilla footage, made by a film cooperative in Sarajevo, of bloodied bodies lined up on a sidewalk, including that of a young woman initially seen lying in a circle of gore, the top of her head blown off. The clumsy efforts of a couple of men to move her body amplify our sense of horror, revulsion and outrage.

Stan Brakhage, film still from Kindering. Courtesy the Estate of Stan Brakhage and www.fredcamper.com, Presentation House Gallery.

These compressed moments alternate with those of cats and cat kisses, a large, silent bird in flight, smaller birds sitting in the bare branches of trees, a baby nursing at its mother’s breast, close-up shots of heterosexual intercourse and a human mouth sucking up long, thick strands of noodles. This latter image works as a kind of ominous intermediary between images of pleasure and life affirmation and those of war, death and rupture. As seen here, the sucking of noodles is more rapacious than erotic and forges a direct connection between unexamined consumerism and violent militarism. (During her talks, Schneemann asserted that her work is about contrasting life’s pleasures with the forces determined to destroy them: time, psychotic violence, bellicosity….)

Initially, the images of Schneemann’s being French-kissed by her cat are troubling— another challenge to another powerful cultural taboo, not to mention the agitating of our anxieties around hygiene and animal-borne disease. Why are they there? After a couple of viewings, it occurred to me: it’s as if Schneemann were saying, “Why is society disturbed by cat kisses when it sanctions acts of outright slaughter and brutality?” Why, the film asks us, is there no outraged taboo against the waging of war?

Brakhage was represented at PHG by four of his late films: Kindering, 1987; Loud Visual Noises, 1987; Christ Mass Sex Dance, 1991; and Crack Glass Eulogy, 1992. Unlike his earlier silent works, each of these short films is accompanied by a soundtrack, as experimental as the visuals and ranging from found to computer- manufactured sound. Brakhage is admired for his early recognition that film, in the mid-1950s, had not begun to explore and exploit its visual potential, locked as it was into narrative and theatrical traditions. He sought to free film from such restrictive conventions, while still paying homage to its relationship to photography. He also sought to align film with Abstract Expressionism, an impulse still visible in the 1980s and 1990s through the gestural forms and calligraphic strands and dots of light and colour that often play across the screen.

In Loud Visual Noises, for instance, Brakhage must have painted colour and gesture directly onto his film. These nonfigurative images—an extended Ab Ex painting—scroll by against a soundscape of hammering sounds, train noises and the repeated, distorted phrase, “Oh my god, oh my god, oh my god.” In other works, Brakhage has either altered the photographic image, blurring it or stretching it, or has cloaked it in darkness. Scarcely articulated forms and textures and tenuous dots and dashes of light emerge from—and then disappear again into—the encompassing gloom. It’s as if Brakhage’s medium were giving birth to itself, calling itself out of darkness and chaos, assembling its own body and limbs and facial features. Assembling its own being.

Not incidentally, James Tenney’s Blue Suede is the soundtrack to Christ Mass Sex Dance: smeared and groaning sounds playing behind flickering scratches of light. Tenney’s fleeting presence seems to close and complete the extraordinary circle of friendship and creativity invoked here. Beneath their formal innovations, both Schneemann and Brakhage manifest a deep moral intelligence, a sensitivity to the revelations of the unconscious and a sustained critique of abusive power. ■

Carolee Schneemann, DEVOUR and Stan Brakhage, “About Time: Four Late Stan Brakhage Films,” was exhibited at Presentation House Gallery in North Vancouver from March 11 to April 9, 2006.

Robin Laurence is a writer, curator and a Contributing Editor to Border Crossings from Vancouver.