Carolee Schneemann

The amount of video around these days is reaching the point of saturation. A friend, a video artist and educator in the UK, tells me that it’s become the fallback position in the art schools-if you can’t think of anything else to do, you make a video. Lately I’ve had a growing desire to see something I’d call “extreme video,” which means I’d have to strap on the gear and scale a 30-metre wall to see the monitor, or bungee jump into the abyss to find a screen waiting where my nose comes to a stop, before I snap back into the air. Then in November I attended a lecture by Carolee Schneemann, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, as part of the “Global Village: the 60s” exhibition currently on view, where she talked about her body of work and screened her most recent video project. The new work pushed me over the edge in to a free fall, no gear, no parachute and no hope for a soft landing.

Carolee Schneemann’s new video installation, entitled Devour, is startling in its directness and disturbing in its poignancy. It initially screened at Eyebeam in New York this past November with Schneemann participating in a residency that enabled her to process the video she’d collected over the last four years. It was an eight-minute, looped, multichannel installation incorporating seven projections of varying sizes. In Montreal she showed a two screen version. I was caught like a deer in headlights, the fugal layering of imagery assaulting me with a series of dichotomous collisions and viscerally charged manic swings as I navigated the familiar, the disturbing, the shocking and the silly.

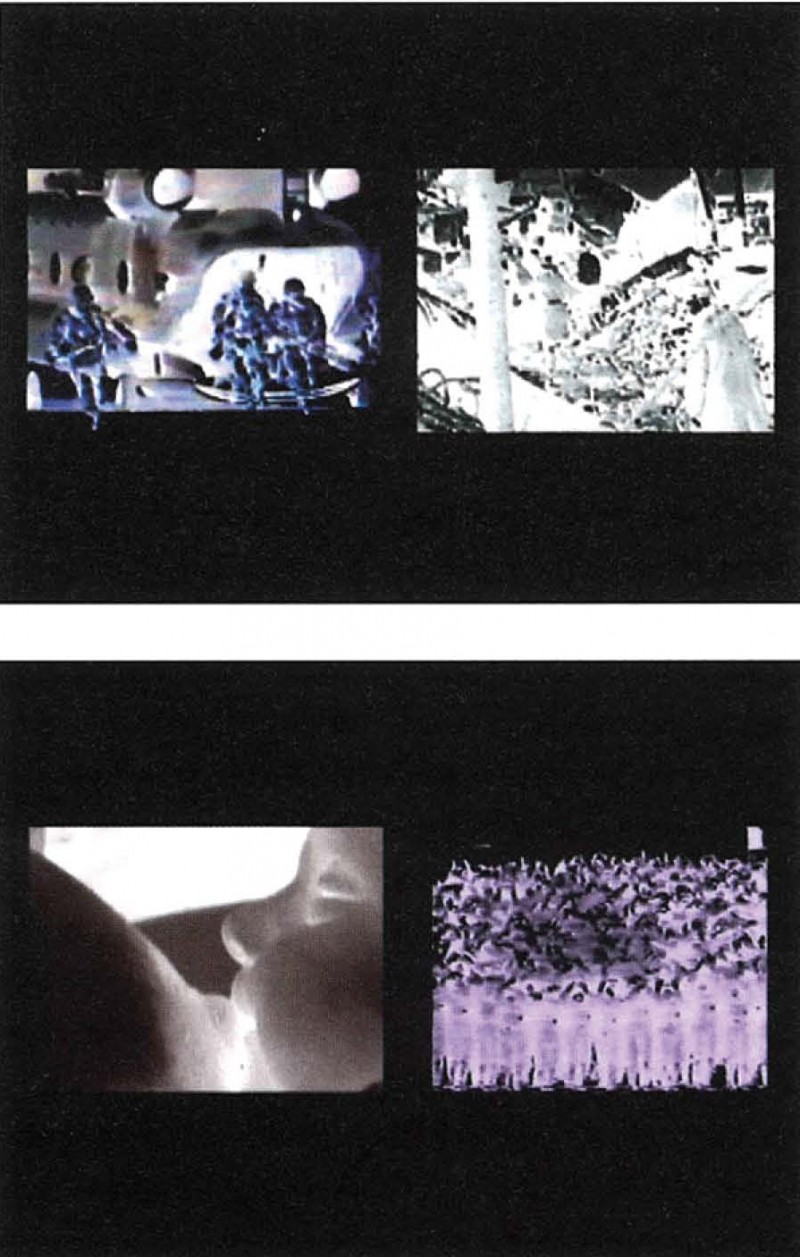

The interlaced video fragments are ordinary, domestic and sensuous, juxtaposed with media clips of war, the damaged and the destroyed. Most clips have been altered for colour, contrast and speed. It starts with black and white abstracted shapes, then cuts to a negative close-up on both screens of a man getting a shave with a straight razor, then the screens split to a negative of a demolition derby in slow motion, we hear the crowds cheer, then a cat is scratching at something, now people scattering, war, the cat, a suckling baby, war, a plane taking off, a bird taking flight, birds in a tree, the plane, a cat kissing the artist, soldiers jumping out of a helicopter, a saturated red image of noodles being sucked into a mouth, the demolition derby, a BeeGees song, a woman wiLh her head blown off, snow, a wounded man crawling away, an erect penis penetrating a vagina, cat kisses and, again, the headless woman.

Carolee Schneeman, video stills from DEVOUR, 2003. Photographs courtesy of Eyebeam Atelier, New York.

Repeatedly, an intimate domestic image draws us in, then an image like the headless woman, a casualty of war, pushes us away. I wanted to avert my eye more than once but it occurred to me that these were images I could see on the evening newscast. We live in a culture that domesticates violence and assigns it a certain entertainment value. What made these images more disturbing were the juxtapositions and the way each image has been digitally manipulated, reinforcing the bleed between signifiers. The viewer is destabilized, caught in the fade, slip and cut as the images move relentlessly through time. Even the cat kisses are jarring as we slide between the clichéd crazy cat lady down the street and the graphic representations of human tragedy and impending doom. Innocent images are suddenly ominous and tragedy is reduced to the mundane.

Early video artists like Dan Graham, Douglas Davis, Paul Wong, Adrian Piper, Lisa Steele and Carolee Schneemann made works that were gritty, rough and challenging. Graham, using the simplest of means, revealed the complexities behind our assumptions about what we think we know and see-and he did it without any tricks. Video did things that only video could do. When we started messing with the pixels, using digital tools called palettes, brushes and paint buckets, the whole thing changed. New media was suddenly old and video was painting. Often I see work today that’s really about nothing more than filling space and time with banal images subjected to a number of macros, transitions and filters. After more than a decade of video painting, I’ve reached a chronic state of pixel fatigue. Devour makes video interesting again. Schneemann’s approach is to be direct and as clear as possible. A social activist, she has dealt with the big issues head-on: the Vietnam war, feminism, sexuality, death. The art historical importance of works like Meat Joy, 1964, Fuses, 1964-67, and Interior Scroll, 1975, stand as a testament to the efficacy of her practice. Devour reveals the urgency in Schneemann’s work to be of the moment and vital to an understanding of contemporary experience. Simply put, it’s about life .•

Carolee Schneemann’s Devour was presented at the DIA Center for the Arts in New York on February 14, 2003. Devour was at the Eyebeam Atelier in New York from October 23 to November 15, 2003.”

Randall Anderson has exhibited and performed internationally over the past 15 years. In Canada, his work has been shown at A.K.A. in Saskatoon, the Contemporary Art Gallery and Western Front in Vancouver, Mercer Union in Toronto, and, most recently, Articule and Circa in Montreal. He is currently living and working in Montreal.