Carol Rama

If I really am so good then I don’t

get why I had to starve so long,

even if I am a woman.

— Carol Rama in 1983

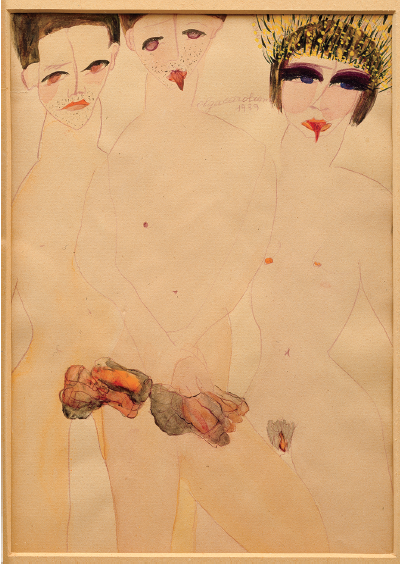

Carol Rama, Passionate (Marta and the Rent Boys), 1939, watercolour on paper, 13 x 9 inches. Photo: Pino dell’Aquila. © Archivio Carol Rama, Turin. Images courtesy of New Museum, New York.

The world paid little heed and she never forgot it. “When I think of the attention I’ve been getting these last few years … I feel sadness … all of this now!?” Carol Rama was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 2003. It would take another 14 years to secure a large-scale retrospective, the most comprehensive exhibit of her work to date, in the United States. Fellow Turin artist Marisa Merz had her first retrospective at the age of 90, Louise Bourgeois was well into her 70s and Carol Rama was nearing 80. Women—especially women who challenge the mainstream— have been largely expunged from the pages of art history. “Carol Rama: Antibodies,” at the New Museum in New York, presented a comprehensive look at an artist whose womanhood is inextricably linked to the startling and singular images she creates.

For Rama, being ‘riled up’ extended not only to her position as an outsider but to her creative constitution: “Rage has always been part of my condition. Fury and violence are what drive me to paint.” Rama was born into the family of a successful bicycle and automotive parts manufacturer, and her childhood was infused with the materials and memories of factory life. But that blissful state was interrupted when the economy took a turn at the end of the 1920s. Her father declared bankruptcy and her once secure middle-class family was socially marginalized. Gone were the afternoons of singing operatic arias and taking riding lessons. Rama said, “I started to experience rejection and derision from the same circles that had showered me with privileges before.” Carol Rama’s mother, Marta, was committed to a psychiatric hospital in 1933; Rama was 15 years old. Six years later, Amabile, Rama’s father, committed suicide.

“Antibodies” opens with a modestly sized self-portrait of the artist from 1937. Vastly different from her other bodies of work, the portrait stands alone, an outsider among ‘others.’ The figure of a young girl is depicted in thick, impasto-like paint. Head in hand, her face and club-like hands are a light, baby-shit brown. Dark smears for eyes convey a wearied expression. Colour here seems oppressive in its application; a blue collar defines the full curvature of her neck. The girl wears a harlequin-patterned front piece overtop heavy black sleeves. Here, the harlequin brings a slew of associations, from the comic servant to a diamond-patterned scaling of snakes. The black humour, perhaps, for which Rama is known.

The artist’s earliest series was completed in the years spent visiting her mother in the asylum. The unorthodox behaviour of the residents became her first subject. Motley, mysterious little watercolours, these works are charged with nefarious activities and furtive desires—monstrous yet whimsical. She depicts women in various states of confinement, enveloped in leaden wheelchairs, or in asylum beds with black, belt-like restraints. Yet, her figures seem to defy restriction. Naked, except for high-heeled shoes, they wear crowns of flowers and gold, wagging their tongues in acts of seduction, personal pleasure and, at times, defiance. In Appassionata, 1943, a young woman kneels, eyes confronting the viewer as two young men, their sex organs multiplied, loom next to her. In Rama’s “Dorina” series, women recline while dark snakes emerge from them. Are they copulating with, or giving birth to, the snakes? Never shying away from the extremes, Rama’s work is explicit, if at certain moments grotesque. Excrement, bestiality, prosthetics, insanity, fury: nothing is excluded from Rama’s creative catalyst.

These works were more than a repressive Fascist regime could accept; in 1945, police censored her first exhibit. Rama turned to abstraction in the 1950s, but it was not long before her regular canvases became festering, fluid-like explosions of bodily functions. She used animal fur, bone, metal gear parts and syringes to populate the red and black smears of textured surface. In Bricolage, 1986, the image on the exhibit catalogue, white semen-like fluid is splattered against a black background. Dismembered dolls’ eyes colonize little pools of liquid resin, like a disease.

The most subdued, if not perhaps the most intriguing, work of the exhibit is her collaged bits of bicycle parts, a nod to her father and his former bicycle factory. The field of colour Rama achieves with the rubber material is surprisingly painterly. In Movimento e Immobilità di Birnam (Movement and Immobility of Birnam), 1977, bundles of deflated tubes hang from a delicate metal hanger, flaccid like industrial entrails or udders. They challenge the two-dimensionality of the support surface, a body floating in (and out of) space. In another, Presagi di Birnam (Omens of Birnam), 1979–95, Rama embroiders the mark of three section cuts—an architectural device—beside a black and red rubbery body. A box filled with the section cut marks, sewn in succession, reads like a cardiogram. Birnam is the wooded area in Shakespeare’s Macbeth and it is hard not to draw an association between the fallen king and Rama’s late father.

Nowhere is her affinity for myth and folklore greater than in her mixed media works of the 1980s when Rama returned to figuration. Curator Lea Vergine included her in the exhibition “The Other Half of the Avant-Garde: 1910–1940,” giving Rama the encouragement necessary to revisit past tropes. She used found architectural plans and mechanical drawings, images that would give her a ground to populate with erotic figures, frogs, bulls and mythological beasts. The tongue returns as an object of eros, a favourite with Rama, as the organ that never ages.

Drawing the curtains on Rama’s art exposes a delicate world of darkness filled with self-induced obsessions, curiosities and convictions. Her work is at once absorbing and outlandish. Much like the little girl who imagined herself in love with her pet frog, Rama reminds us that there is a little bit of an outsider in all of us.

“I believe there is no freedom without derangement. But then, we are all pretty deranged.” ❚

“Antibodies” was exhibited at the New Museum, New York, from April 26 to September 10, 2017.

Elyssa Stelman lives and works in Winnipeg.