Bunny + Tree = Bunnies and Trees

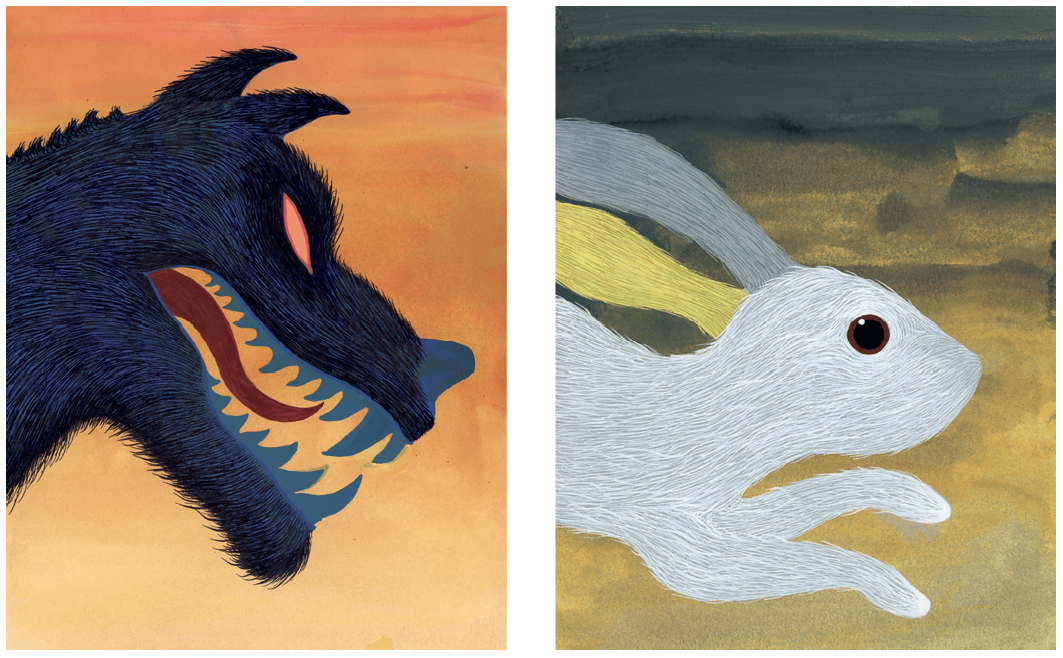

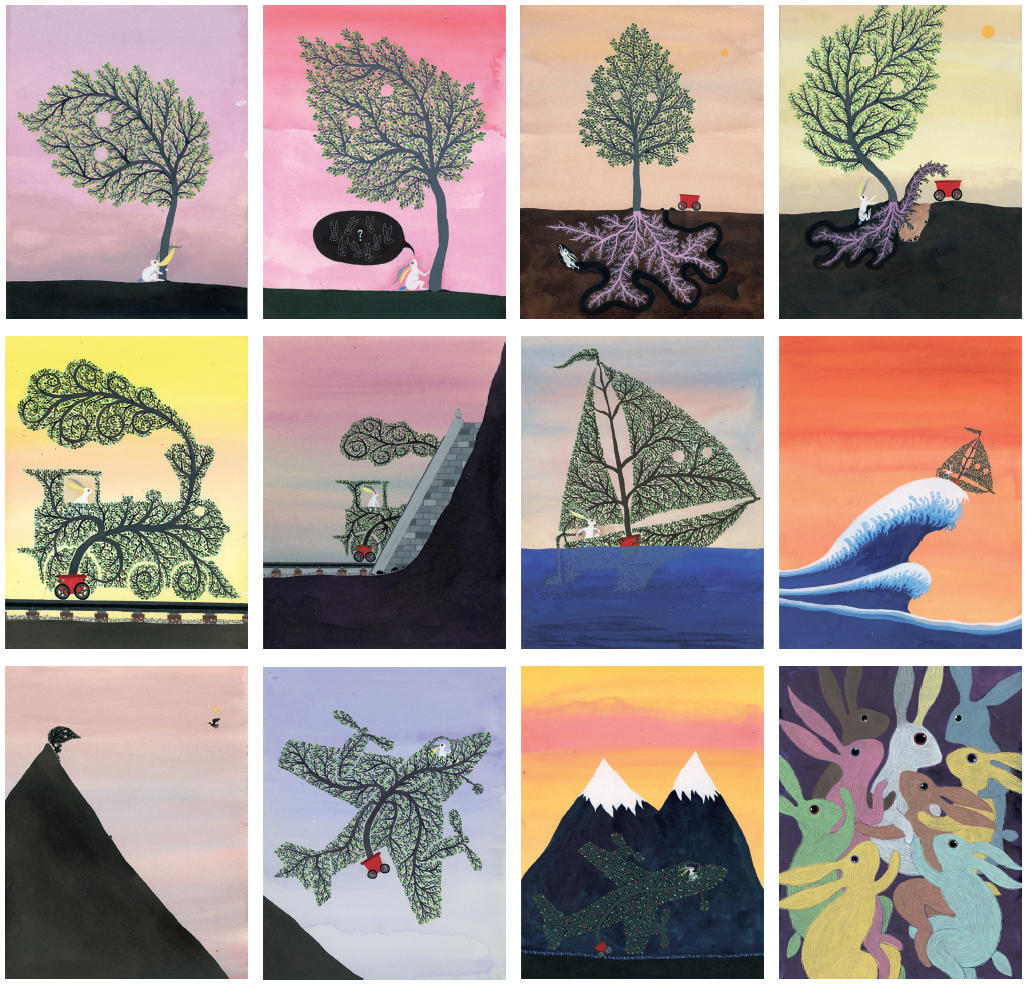

Balint Zsako, the Los Angeles-based Canadian artist, began his children’s book four years ago by setting a problem for himself. He had been reading storybooks to his three-year-old son and noticed how much they relied on written language to convey the narrative and how closely tied were the pictures to the words. “As a challenge, I was curious to see if you could get the same nuance and subtlety in the narrative relationships without using words.” The result of his problem-solving is Bunny & Tree, a 196-page story in which the eponymous characters establish a life-saving and generative closeness. The story also involves a brief introduction of a wolf and, more prominently, a family of eight additional rabbits. Except for a few punctuation marks and some thought-balloons with pictographs, Zsako never strays from his wordless plan. This result ends up being worth thousands of words.

The other limitation he set for himself was that no emotion could be indicated through facial expression. He wanted the bodies to convey what the characters intended; the lean of the tree in space would mark aggression, the touch of a furry ear on bark would speak to comfort. In one especially poignant painting, after the tree has driven away the ravenous wolf (Tree’s magical properties are never explained), Bunny wraps its paws and both of its long ears around Tree’s trunk in a gesture of thanks. In another painting, Tree stands in a vast, empty space, looking bereft, waiting for Bunny’s return. At one point in the story, the wolf is a balletic wonder, as if Matisse had painted a blue predator clothed in fur.

_1100_1415_90.jpg)

Balint Zsako, Bunny & Tree, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2023 [excerpts]. Images courtesy the artist.

Balint Zsako, Bunny & Tree, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2023 [excerpts]. Images courtesy the artist.

_1100_707_90.jpg)

Balint Zsako, Bunny & Tree, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2023 [excerpts]. Images courtesy the artist.

_1100_707_90.jpg)

Balint Zsako, Bunny & Tree, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2023 [excerpts]. Images courtesy the artist.

Balint Zsako, Bunny & Tree, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2023 [excerpts]. Images courtesy the artist.

The picture story is told through an acute awareness of other artists. When Bunny is being transported by Tree in the form of a boat, the pair hover on top of a gigantic wave copied from Hokusai’s famous 1831 woodblock print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa; a mountainous sky has the scumbled turbulence of a Turner seascape, or the resonant depth of a Rothko abstraction; when the protagonists enter a black tunnel, the atmosphere intimates Munch, or Chris Ofili’s threatening darkness.

_1100_707_90.jpg)

Balint Zsako, Bunny & Tree, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2023 [excerpts]. Images courtesy the artist.

_1024_1317_90.jpg)

Balint Zsako, Bunny & Tree, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2023 [excerpts]. Images courtesy the artist.

_1100_707_90.jpg)

Balint Zsako, Bunny & Tree, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2023 [excerpts]. Images courtesy the artist.

_1100_707_90.jpg)

Balint Zsako, Bunny & Tree, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2023 [excerpts]. Images courtesy the artist.

_1100_707_90.jpg)

Balint Zsako, Bunny & Tree, published by Enchanted Lion Books, 2023 [excerpts]. Images courtesy the artist.

Zsako used this sourcing to keep his story open-ended. “The way influence works is that the viewer is offered a rich amalgamation of all my looking and thinking about art built up over a long period of time.” He cites a myriad of pictorial sources, including Hungarian folk painting, Mughal miniatures, Inuit prints, medieval book illustration, drawings by Ken Price and Bill Traylor, watercolours by Emil Nolde and ink drawings by Victor Hugo. “Over the four years I made the book, I probably absorbed a thousand references. That’s the wonderful thing about art; we are sponges, we make things with a lot of intuition and intelligence, and we receive them the same way.”

Zsako’s visual knowledge informs the story at every level, but there is a larger frame in which the narrative develops. The book is a journey during which Bunny and Tree encounter a series of natural locations that have to be overcome. These obstacles are shaping: transportation necessarily becomes transformation; Tree assumes the form of a locomotive, a boat, an airplane and even a food source for Bunny’s family when they turn up later in the story. Zsako decided that Tree would become whatever Bunny asked it to, and these requests oblige the narrative to correspond to the working of the imagination; it’s in a state of constantly changing possibility. The final shape-shifting turns Tree to food and food to fertilized roots, and the narrative loops into a cycle of natural renewal and mutual sustenance. But at the centre of Balint Zsako’s artful, wordless story is another cycle of renewal: the story of how art seeds art. Just as with rabbits and plants, art embodies its own fecundity. It is most discriminantly and naturally productive.

Bunny & Tree will be published by Enchanted Lion Books in Brooklyn, NY, in the spring of 2023. ❚