Building Ideas

Four Exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art

As I write this article we are in the beginning stages of quarantine. It’s more than bizarre to discuss the shows inside the Museum of Contemporary Art in Toronto, a place that is around the corner from my house but which currently stands closed and empty of people. It’s true there are no visitors, but the art is still there, and I wonder if the unobserved world of the museum is changed by the absence of its requisite viewers. Certainly, my relationship to the exhibitions has changed, and the performances and talks that were scheduled to happen there were cancelled. In a matter of weeks, the art world has “moved online,” and it has become obvious—at least to me—that digital photographs, virtual exhibitions and Zoom events cannot supplant actual experience. The centrality of the photographic image at this moment sent me to reread Susan Sontag’s On Photography because even as our advanced industrial society takes a sudden, unexpected break, the photograph is working overtime “as a spectacle (for masses) and as an object of surveillance (for rulers).”

There are no photographs that could accurately capture the exhibitions in this unusual and historic building. The scale of the artworks and installations and their interaction with the museum’s architecture, layout and communal ecology resist attempts at flattening at all costs. I think many artists are practising in a way that privileges seeing their work in person; this certainly applies to the ones exhibited here. “It’s very hard to photograph my work,” said Carlos Bunga, whose large cardboard installations and sculptures occupy several spaces in the museum. “You can’t take a picture of the whole piece,” he says, “and I have the idea that something escapes from you, especially in the picture.”

Bunga’s quasi-architectural installation Procession, 2020, on the museum’s ground floor sets up the tone or experience of the (four) successive floors, like the first stage of grief, love or heaven but with a certain amount of blindness. Procession is so effectively camouflaged into the space that it is easy to miss it. This is typical of his cardboard works, which seem to suction themselves to the walls and floor of whatever room is housing them, before disappearing. In this case, he’s constructed a false colonnade amid the museum’s existing concrete columns.

Carlos Bunga, Untitled, 2020, MOCA, Toronto. Photos: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy the artist, Galeria Elba Benitz, Madrid, and Alexander and Bonin, New York.

Bunga’s colonnade, only three feet shorter than the actual ceiling, is painted pastel blue, peach and baby pink. Applied fairly casually and over areas of industrial glue that holds the structure together, the paint crackles and separates in a pattern evoking stretched skin. Paradoxically, the strongest effect of this work is how easily you forget about it. Like a massive chameleon, it blends in, demonstrating the power of mirroring and mimicry in obscuring structures and systems that are in plain sight.

Bunga’s cardboard installation Occupy, 2020, on the museum’s second floor, is more imposing than Procession. Viewers can walk around in a sea of connected cardboard boxes resting on the floor, taking off their shoes and stepping carefully from cubby to cubby. I think now of these empty boxes—inside an empty museum, inside a quarantined city—like a set of unfortunate nesting dolls. But this is not the first time this building has been empty, and this current history is a more uplifting story.

Erected in 1920 by the Northern Aluminum Company, the 10-storey building was an early industrial high-rise in Toronto, displaying typical modernist features, such as its exposed concrete framing. The company produced cooking utensils, shifted to military supplies during the wars, then diversified to make appliance components and parts for Ford Motors. The building received heritage status in 2005, but the factory closed a year later, leaving the building abandoned for over a decade. It became a site for raves and graffiti artists at a time when development in the city was slow, its heritage status and structural sturdiness keeping it from almost certain destruction. If it were not so well built, the owners might have used a tactic known as “demolition by neglect” to make the land easier to sell. But the building was strong. It survived.

Megan Rooney, installation view, “HUSH SKY MURMUR HOLE,” 2020, MOCA, Toronto. Courtesy the artist and DREI, Cologne.

As a functional art museum, however, its prominent mushroom columns are challenging for artists to work around, forcing them to use tactics like camouflage and mirroring. This is the case for Megan Rooney’s exhibition “HUSH SKY MURMUR HOLE,” which occupies the entire third floor. Abstract, pastel murals cover the walls, made by applying successive layers of paint that she removes using a power sander, forming a heterogeneous pattern that mimics the raw patchiness of the museum’s concrete columns. There are assemblage sculptures throughout the space, intentionally sparse to leave room for live dance performances—all of which have been postponed. “A lot of the choreography was made as a response to the columns, giving you a path-like movement through the space,” Rooney noted. For now, these performances must be left to the imagination.

The gentle, rosy tones of her murals create a sense of well-being immediately contradicted by the sculptural works, which are made of traffic control devices like orange cones and flashers, and combined with domestic objects such as a bathmat and towels. A grocery shopping cart stands in one end of the space with an empty baby carrier inside. Human figures constructed from stuffed fabric sit cross-legged on the floor behind crowd control gates. Large garden umbrellas that look dirty and abandoned hang from the ceiling. The entire scene evokes a neighbourhood street party gone wrong.

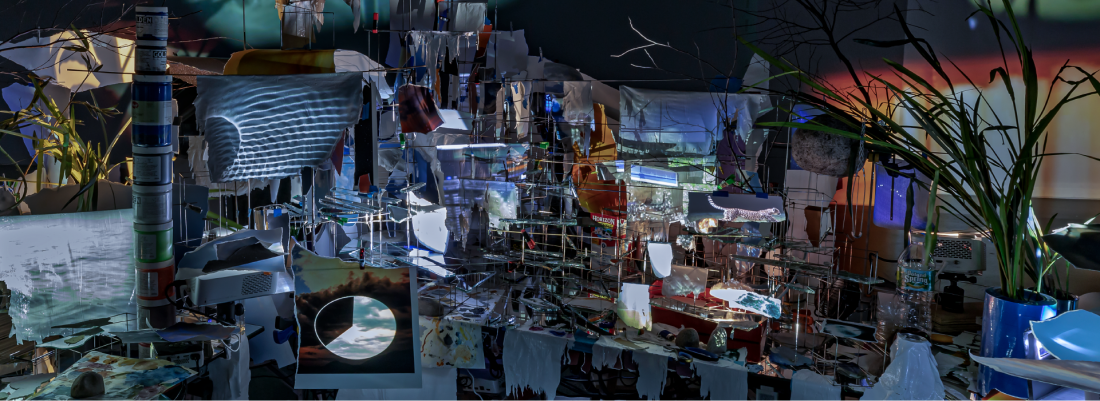

Sarah Sze, Images in Debris, 2018, MOCA, Toronto. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro Gallery, London, and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Los Angeles.

Recalling historical movements like Italian arte povera and surrealist assemblage, the artists in these exhibitions seem interested in subverting the commodification of the art object by making ephemeral works and using scrappy, inexpensive materials. Sarah Sze’s installation Images in Debris, 2018, is an intricate accumulation of studio supplies and projectors. Loosely based on the artist’s own desk, there is everything from scissors, dry paint skins and tape, to toilet paper, Advil and a jar of mayonnaise. The projectors are pointed at the walls, playing various scenes of nature. A metronomic soundtrack akin to the sound of radar makes the installation read like a station from which children or aliens are monitoring Planet Earth. Like Rooney’s pastel world, this work is whimsical, with underlying intimations of loss.

On the final floor, Shelagh Keeley’s exhibition “An Embodied Haptic Space” circles back to the building itself with a display of photographs she took inside the museum before it was renovated. These are printed on vinyl and are adhered to the wall alongside ephemeral murals and drawings of loose floor plans on Mylar. Keeley’s brushwork is free and expressive, echoing the balance between chance and intention that can accompany a building project. She could not have known then, when taking those pictures, that this show would take place, and neither did the factory workers who toiled here 100 years ago know what would become of their workplace, or of Toronto.

Shelagh Keeley, Fragments of the Factory unfinished Traces of Labour, 2020, from “An Embodied Haptic Space,” MOCA, Toronto. Courtesy the artist.

Keeley’s photographs of the dilapidated building as it was, with peeling paint and piles of broken tile, are the most powerful and disturbing things in the museum. This is uncontestable proof of the alarming march of time. “Photography is the inventory of mortality,” Sontag wrote in On Photography in 1973. “Photographs state the innocence, the vulnerability of lives heading toward their own destruction, and this link between photography and death haunts all photographs of people.” Although we are not discussing pictures of people, but a building, and one that has been rehabilitated rather than disappearing, the context of global quarantine makes it feel as if everything could easily slip into ruin. As we anticipate massive changes in economics, culture and politics potentially matching the transformations that followed the world wars, I am comforted by this building, which has looked at once decrepit and pristine, and ultimately was strong enough to live 100 years.

“HUSH SKY MURMUR HOLE” by Megan Rooney will be on view until September 13, 2020. “An Embodied Haptic Space” by Shelagh Keeley will be on view until September 27, 2020. “Images in Debris” by Sarah Sze and “A Sudden Beginning” by Carlos Bunga will be on view until October 4, 2020.

All four exhibition are being exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto

Anna Kovler is an artist and writer living in Toronto.