Bruce Nauman

The Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (MACM) mounted a two-part exhibition of the work of American artist Bruce Nauman, consisting of some of the most significant works from the last four decades. Of the two-part presentation, one, entitled “Elusive Signs: Bruce Nauman Works with Light” and organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum, was his work with neon light produced between 1965 and 1985, and the second was a survey of video and installations drawn together for the MACM by Sandra Grant Marchand. Nauman’s work is pivotal to any understanding of art in the last half of the 20th century. One of the most eclectic and curious artists, he has no signature style; however, the neon and several of the video installations in this show probably come closest to defining his body of work. Nauman is an artist whose mind moves swiftly and deftly from one material to another. He tumbles ideas around, finding ways to reveal the unseen or unnoticed; in doing this, he has influenced a generation of artists. His 1968 cast of the underside of a chair, for example, clearly was the impetus for the idea that Rachael Whiteread developed into an entire career.

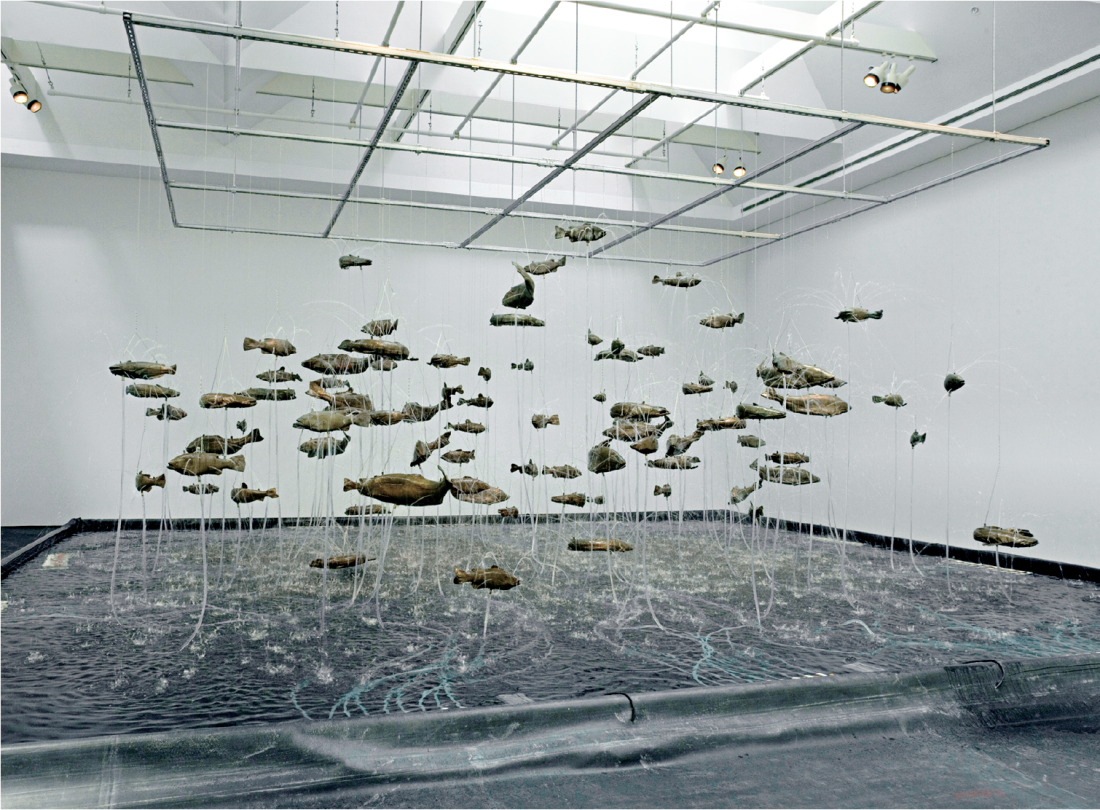

Bruce Nauman, One Hundred Fish Fountain, 2005, 97 bronze fish of different forms, suspended with stainless steel wire from a metal grid, approximate basin dimensions: 8” x 25’ x 28’. Courtesy Donald Young Gallery, Chicago. All images © Bruce Nauman/SODRAC (2007). Photo: Richard-Max Tremblay, Musée d’art contemporain de Montreal.

The two earliest works in neon are Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten-Inch Intervals, 1966, and The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths, 1967. These pieces lay the foundation for all the work that followed. Neon Templates sets in place Nauman’s interest in the position of the body within all his work. Consistently he locates the body in relation to itself, other bodies and the space in which it is situated. Like a kind of neon death mask, Neon Templates speaks to both the body that once was and the body that looks on. Mystic Truths, on the other hand, addresses the studio, the place where the artist creates and questions the work. What does an artist do? Within the isolation of the studio, this is the question that makes or breaks all artists. In a way, the statement pokes fun at the higher calling of art making while stating a truth that, irrational or not, keeps the creative process in motion.

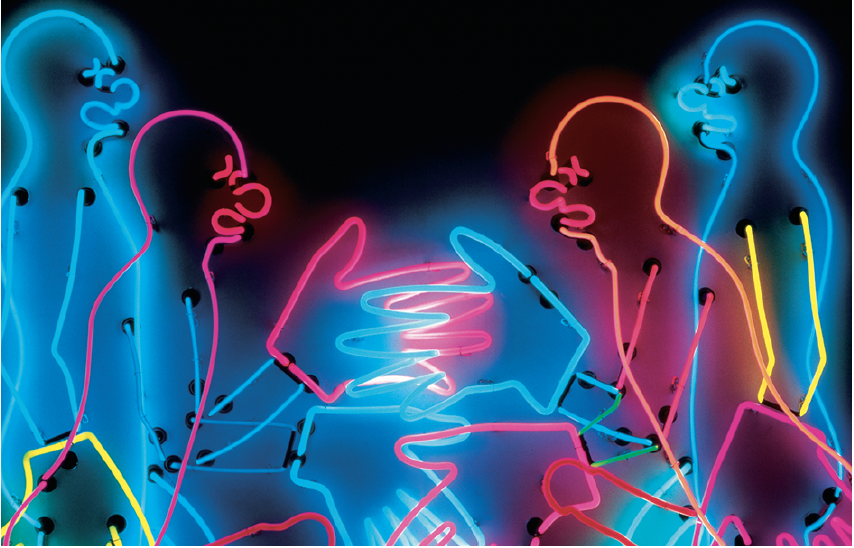

Bruce Nauman, Mean Clown Welcome, 1985, neon tubing mounted on metal monolith, 72 x 82 x 13”. Udo and Anette Brandhorst Collection, Cologne. Courtesy Donald Young Gallery, Chicago.

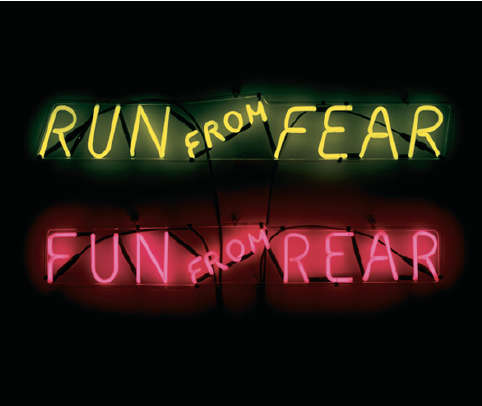

Say a word over and over again and eventually, you trip up. The sharp edge of Nauman’s work inhabits this stumble, the break in the patterns of perception and understanding, where laughter can turn to tears and meaning is as intangible as air. With the simplest of word games, the most inane bad humour and subtle shifts in simple rules, Nauman has a way of making us question the ground on which we stand. Neon words flash: Violins, Violence, Silence, 1981–82; another work is a flashing text circle reading “LIFE, DEATH, LOVE, HATE, PLEASURE, PAIN.” The figurative neon pieces show male bodies engaging with one another, reaching to shake a hand that gets pulled away, marching in a row, legs extending, penises becoming erect, hands reaching. The work positions the body within a fluid matrix of verbal and visual clichés that bait us, including us in the gag, the club, the in-crowd, before turning to point an accusing finger, illuminating our complicity in—what? The artist never explicitly says, but clearly things aren’t as they seem and what we think we know is merely another construction masquerading as fact, ready to disassemble at any moment. Mixed messages, bright colours, funny images, doom and the looming potential for violence keep the body in a defensive position. There is no comfort zone.

Bruce Nauman, Run from Fear, Fun from Rear, 1972, neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frame, two parts, 8 x 24 x 2 1/2” each. Ed. 4/6, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Gerald S. Elliott Collection.

For me, the video installation entitled Clown Torture is Nauman’s most significant work. I’ve seen it many times since I first encountered it shortly after it was made in 1987. I have logged serious time sitting in rooms, watching these clowns go through their painfully repetitious torture rituals. On two large projections and two stacked pairs of monitors, a clown is trapped in behavioural loops. In one, a clown yells, “NO, NO, NO” over and over, falling on his back and kicking his legs in the air. On another, the clown sits, waiting, on a toilet in a public washroom, and on another, he enters through a door where a bucket of water falls on his head, then he does it all over again. The loops begin to fold in on each other, the action vacillating between hilarious and terrifying. The piece always leaves me at a loss for words. It nails me in the gut. I can’t think of any other video installation that so effectively uses the medium to derail perceptions. Nauman relentlessly pushes us off balance. There is no hope in this piece, only the inexorable folly that is the human project.

Over the years I’ve seen Nauman’s light pieces many times, but never together in one exhibition. This was a rare opportunity to consider the works in relation to one another. From the early word games to the later cartoon-like jokes, Nauman illuminates the absurd and the painfully ridiculous stuff of life. ■

“Bruce Nauman,” curated by Sandra Grant Marchand, was exhibited at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal from May 26 to September 3, 2007.

Randall Anderson is an artist and writer living in Montreal. He recently received a commission for a public sculpture at Concordia University’s Fine Arts building.