Brian Groombridge

The three small rooms of Brian Groombridge’s retrospective at YYZ were unique and spacious precincts populated by words and numbers, signals and signs. Printed onto objects or positioned as titles, words in themselves seemed to take on the qualities of things, giving the term “printed matter” a new turn. Paradoxically, Groombridge’s few objects without texts or titles possessed something of the transitory or provisional qualities of words. The forms of two untitled painted aluminum sculptures from 2008 suggest “chair” and “radio” respectively, as if thought has retained its status as thought while having become precisely haptic, something you want to hold in your hand. The “radio” is composed of two small rectangles screwed together at a right angle. A circle is cut into the vertical. Its geometry and palette link it to De Stijl but it cannot be said to represent any precisely historical style. The “chair” is flat, about one inch thick. It looks like a criss-crossed, possibly modernist, diagrammatic cut-out. Projecting out from its blueness are three small square and rectangular plates: white, yellow and grey complications of flatness and chair-ness. Neither mobile nor stabile (to use Calder’s terms) it hangs still from the ceiling, by a wire. Its suspension is a matter of fact, and also a condition.

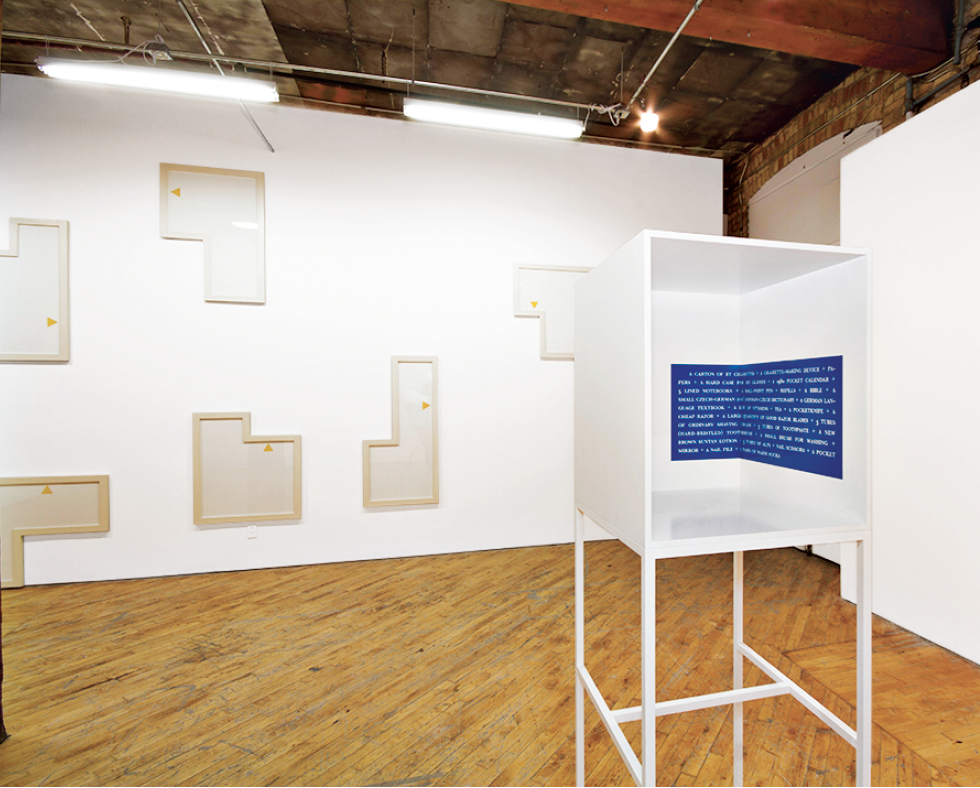

“Brian Groombridge: small telescopes,” installation view. 50° 06” 0’ N, 14° 15” 0’ E, 2005, (foreground), Tati, 2000, (background). Courtesy YYZ Artists’ Outlet, Toronto. Photograph: Allan Kosmajac

Produced between 1989 and 2012, the works at YYZ evoke familiar forms and formats. A list of these might include the diagram, the measuring device, the museum alcove, the commercial sign, the trade show display device, the child’s game, the poem and the notebook. Here, the provisional and the quotidian, the props of something like daily life, open up into the more vast (though often no less quotidian) spaces of mind, memory and history. The “between” is important in Groombridge. It is a length of interior space that must be travelled before arriving at the totality of the works themselves (a totality, however, that is prone to flux).

One of the works Groombridge produced in 2005 is a three-quarter-metre-high white box on a stand. The box sits about chest height to above head height. You approach it from a distance and are led around it until finding that the box is open on one side. On two interior sides is a list in white type against a wide blue band:

A CARTON OF BT CIGARETTES + A CIGARETTE-MAKING DEVICE + PAPERS + A HARD CASE FOR MY GLASSES + A 1980 POCKET CALENDAR + 5 LINED NOTEBOOKS + A BALL-POINT PEN + REFILLS + A BIBLE + A SMALL CZECH-GERMAN AND GERMAN-CZECH DICTIONARY + A GERMAN LAN-GAUGE TEXTBOOK + A LOT OF VITAMINS + TEA + A POCKETKNIFE + A CHEAP RAZOR + A LARGE QUANTITY OF GOOD RAZOR BLADES + 3 TUBES OF ORDINARY SHAVING CREAM + 3 TUBES OF TOOTHPASTE + A NEW (HARD-BRISTLED) TOOTHBRUSH + A SMALL BRUSH FOR WASHING + BROWN SUNTAN LOTION + 3 TUBES OF ALPA + NAIL SCISSORS + A POCKET MIRROR + A NAIL FILE + 2 PAIRS OF WARM SOCKS

This work is named 50° 06” 0’ N, 14° 15” 0’ E. These are the geographic coordinates of the Czech Republic prison where Václav Havel was imprisoned. The list is his, made so that these items, corresponding to his own dignity and survival, could be brought to him by his beloved wife Olga Havlová. Groombridge lifted the exact list and its typeface from Havel’s Letters to Olga, 1988 (Faber & Faber).

Brian Groombridge, Untitled, 2008, painted aluminum and wood, 117 x 40 x 40 cm with pedestal. Courtesy YYZ Artists’ Outlet, Toronto. Photograph: Allan Kosmajac

Groombridge’s is a third-generation approach to the idea of “escaping the frame,” an idea that so obsessed early conceptual art. Not only has the frame been physically returned to (as it was, along with the object, in Groombridge’s teacher, Ian Carr-Harris’s work of the 1970s), but often it has become so integrated into the work that it ceases to call attention to itself. The largest room at YYZ was the most visually delicate of the retrospective, housing six works, including 50° 06” 0’ N, 14° 15” 0’ E, yet seeming close to holding nothing at all (Groombridge is, perhaps, the Richard Tuttle of conceptual art). Scattered at intervals and covering the long wall in this room was Tati, 2000, a work named after and mimicking the “animated gaze” of the French filmmaker Jacques Tati; a series of eight white, enamel-on-board, right-angled shapes framed in white—geometrical units as if representing rooms, where each unit is marked with a pale, yellow triangle, an arrow-like sign indicating the direction of the represented gaze. Seemingly puzzle-like, the units are of different dimensions but take up playfully, precisely the same area. In Groombridge’s work, as in Tati’s, perception, in both of its primary senses, is key. Here, the white frames are borders between the known and the unknown, the empty space within the units, and emptier space between each unit. As in much of Groombridge’s work, one escapes the frame in the space of one’s perception and knowledge. These frames also have an anecdotal life. Tati’s family were frame makers, and Tati, it might be said, as a composer of film frames, followed in their footsteps. His camera rarely seemed to move, so as to admit the viewer into his busy set pieces, an effect of internal movement and external stillness that Groombridge’s work also encourages. ❚

“Brian Groombridge: small telescopes” was exhibited at YYZ, Toronto, from September 8 to December 1, 2012.

E C Woodley is an artist, curator, composer and critic.