Bonnie Devine

Bonnie Devine’s exhibition “Writing Home,” curated by Faye Heavyshield, includes writing, sewing, painting, sculpture and a soundscape. The artist’s purpose is aptly described in the title—an enactment of description directed towards and inscribing a place effected as a representation that invokes desire, the other and the psyche of the author. Writing home. We have all done it. As it turns out, the ostensibly simple act of writing home, with its implied romanticism, has a political specificity within the intersecting terrains of history, treaty making, customs, peoples and stories of origin. For the artist Bonnie Devine of Serpent River, writing home involves others’ letters about home—history and record keeping that must be read through the oppressive regime of colonial culture—as well as her own letters home—sophisticated art objects whose form acknowledges both past and present.

What constitutes, after all, a description of place? Whose description, which technology of representation, and what eventual implications are all questions that are raised by the exhibition.

The show comprises four diptychs, four cast-paper letters, four glass sculptures and a continuous projection of roughly 60 images. There is just enough work to articulate the two long and one short wall of Urban Shaman’s main exhibition space. There are just enough mid-to-long shots in the repeating Power Point to physically locate the artist in the landscape as she makes paper moulds directly on the rock’s surface. These later appear in the exhibition as letters that contain poetic musings and inquiries written by the artist. There are a few long shots of rushing rivers and trees, but most of the projected photos are close-ups of rock striations, patterns, mica, lichens, iron oxide stains and pictographs that are actual or that float at the level of the viewer’s imagination.

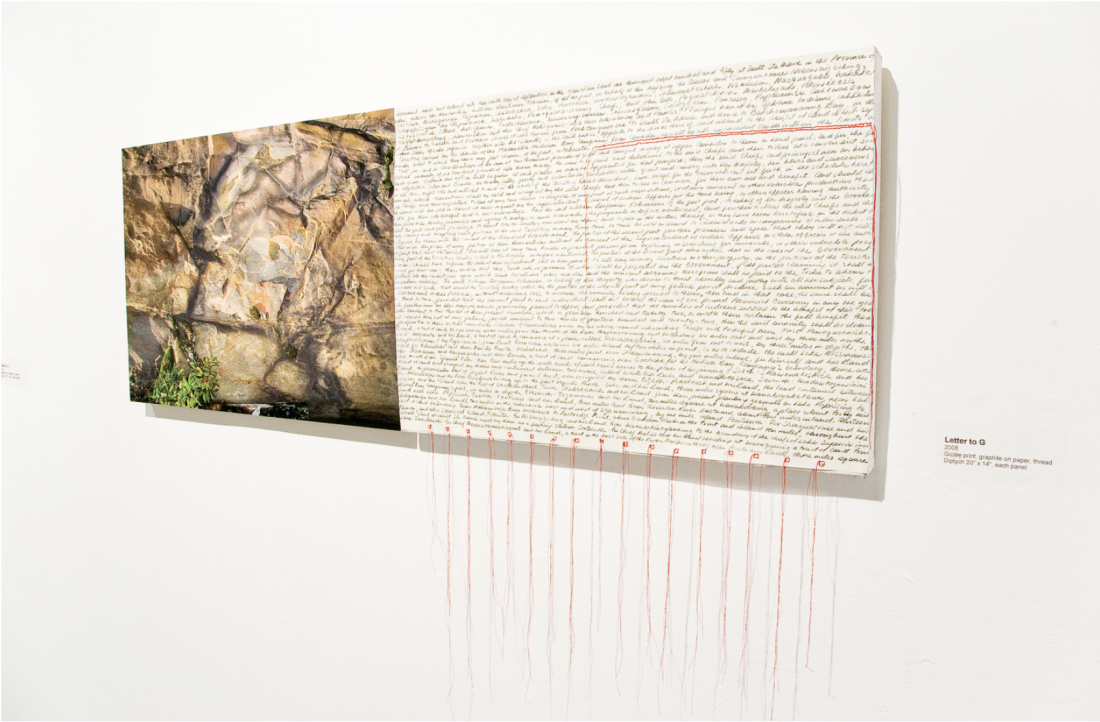

Bonnie Devine, Letter to G, 2008, Giclée print, graphite, paper, thread, 20 x 14”. Photographs: Scott Stephens. All photographs courtesy the Urban Shaman, Winnipeg, and Gallery Connexion, Fredericton.

It’s all striking work. It’s analytical and accessible. The diptychs are the most complex of the objects, overtly engaging the theme of writing. Two of the diptychs are large; two are small. Each contains a close-up of a photographic, Giclée print of rock, twinned by a written and/or sewn component.

In the diptychs, the photographs are consistently about rock—close-ups that invite the viewer to a disorientation about scale while invoking the sensuous surface and calming colours of the land. Devine asserts the primacy of the rock as ancestor and as home. The photographs’ other halves are multifarious. In Letter to W, for example, the photograph is paired with what I imagine is an authentic letter, epic in tone, of an account of the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi. Transcribed by the artist, it is a visually fascinating object. The cursive script is interrupted by four images stained in red oxide. The pictograph-like forms reference textual contents: a man in a hat (the white man), totemic birds (loons and cranes) and another image. In the letter, generations are accounted for, dents are pressed on a copper plate, migrations are made and the significance of the animal totems is asserted.

Like Sherrie Levine before her, Devine re-authors the text, copies the master’s hand, yet at a scale, mutedness and line length that makes reading both legible and obscure. Reading becomes a commitment of physical endurance. The line exceeds the physical space and vision of the viewer. Reading requires rocking and swaying from side to side, and navigating around the stained images. The viewer is conscious of the reading: left to right, subtle movements of down and up, return sweep and, whoops! lost again.

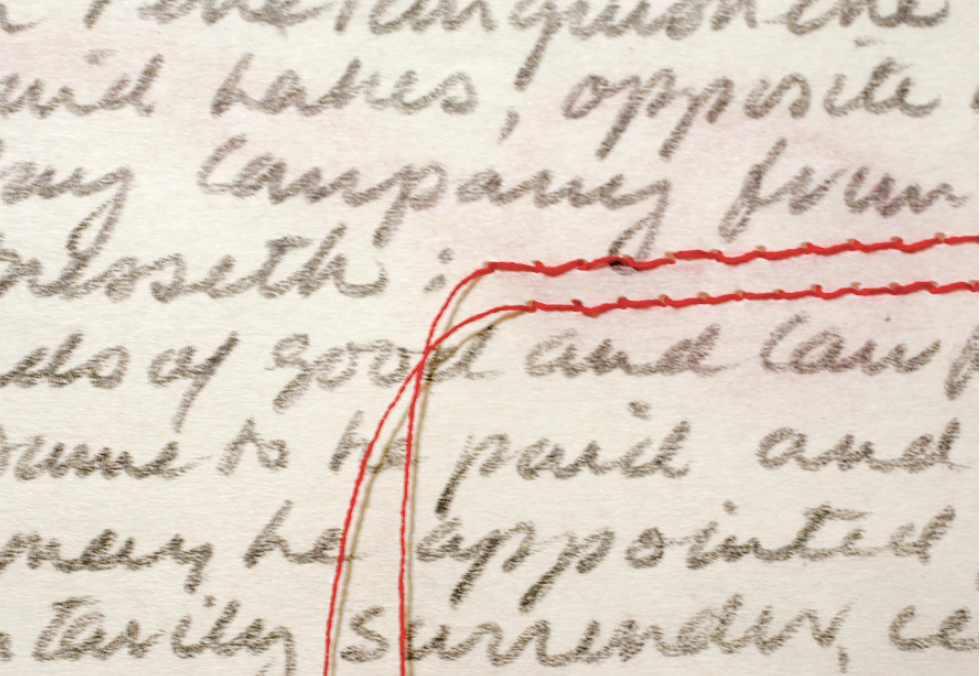

Bonnie Devine, Letter to G (detail), 2008, Giclée print, graphite, paper, thread, 20 x 14”.

Such letters—and Devine uses two other long letters in the four diptychs—generate a problem for description and representation. These accounts of oral history, physical description, cultural knowledge, topography, gender and hearsay cannot be totally dismissed nor accepted. In one of the small diptychs, lines of stitching interrupt the letter space. In another, the writing is completely eclipsed by horizontal bands of stitching in red thread on rectangles that mimic lines of text on a sheet of paper. Writing is replaced by sewing, a movement that invokes the hands of women and another kind of manufacture.

Devine is deft at shifting the technologies. Representational means are foregrounded and smartly considered. “Writing Home” is closer to Martha Rosler’s “The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems” than Lawren Harris’s North of Lake Superior. Along the south wall of the gallery, four glass sculptures are displayed on wall-mounted birch shelving. The sculptural work comes as a formally elegant antidote to the iconic works of image and text. The cool green elegance of the glass reflects and absorbs the light. The sculptures’ height and width at 8 1/2 by 11 inches is based on the size of standard office paper. They have been cast as rectangles of rock, an inscription of place that honours and validates the relationship Devine has to the originary and sacred teachings of her culture. Rock as imaged in photographs and as surface for indexical tracings is everywhere and also nowhere in the gallery: a structuring presence and slippery absence.

Through transcribing, moulding, photographing, staining, sewing and slagging, Devine pushes the limits of what can be told, in a process that invokes the diaristic but never descends to the sentimental. The soundscape, based on the human genome project, is eerie and modern. It is a choice that asserts a broadly human condition that negates any 19th-century understanding about race and that also prevents any romanticization about place. “Writing Home” is suggestive, hinting at important ideas about sovereignty and discursive formations related to paper, writing and power. ❚

“Writing Home” was exhibited at the Urban Shaman Gallery in Winnipeg from February 12 to March 27, 2010. Its first showing was at Galerie Connexion in Fredericton from February 1 to March 21, 2008.

Amy Karlinsky teaches and writes from Winnipeg. She was pleased to see Bonnie Devine’s curatorial work, the retrospective of artist Daphne Odjig, at the Mackenzie Gallery in Regina.