“Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography” by erin o’Hara slavick

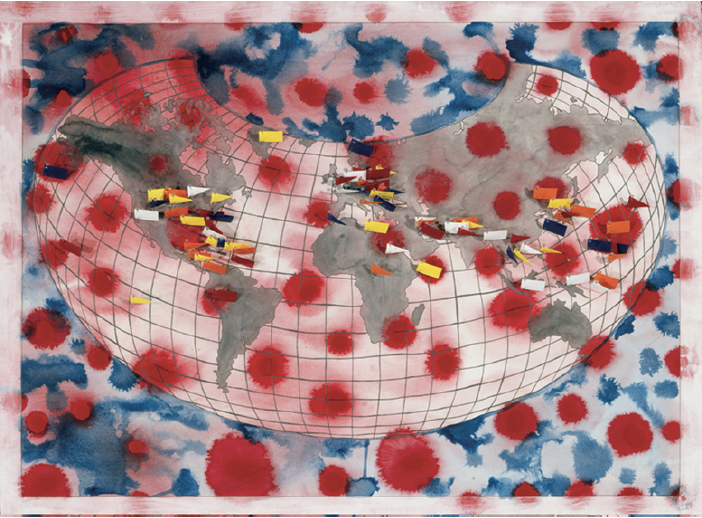

The publication of Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography by elin o’Hara slavick, an artist, activist and educator based in North Carolina, is a welcome contribution. While the dimensions of this artist’s book (a collaborative endeavour both creative and scholarly) are modest, its ethical implications and political protest are magisterial. It reproduces in full colour 49 of o’Hara slavick’s mixed-media works on paper, depicting sites around the world—all from aerial perspectives— that have been bombed by the United States since 1854. As source material for this ongoing series, o’Hara slavick works with maps, aerial photographs and military surveillance imagery of cities and countries that have become the targets of a global superpower exercising its wrath. Dresden, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Guatemala, El Salvador, Haiti, Vietnam, Philadelphia (surprisingly), Kosovo, Afghanistan, Baghdad and Lebanon are just a few of the locations that have been subject to America’s advanced technologies (nuclear, chemical, biological, fi re, etc.).

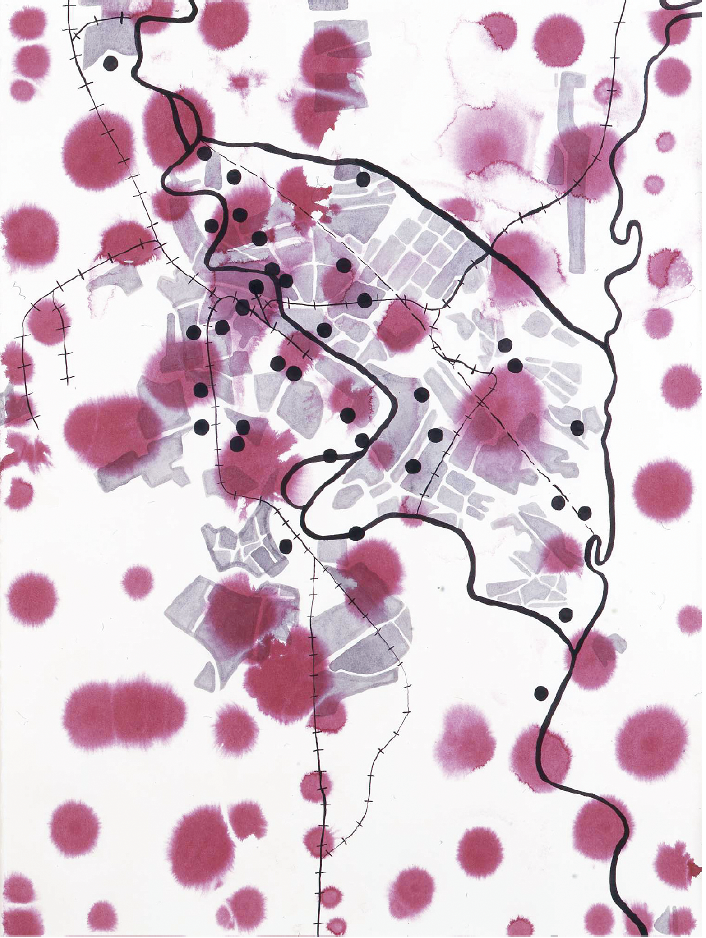

elin o’Hara slavick, Baghdad, Iraq, 1990–Ongoing, 2000–2006, ink, watercolour, gouache, acrylic, graphite, chalk on Arches paper, 30 x 22”. Photo: Christopher Ciccone.

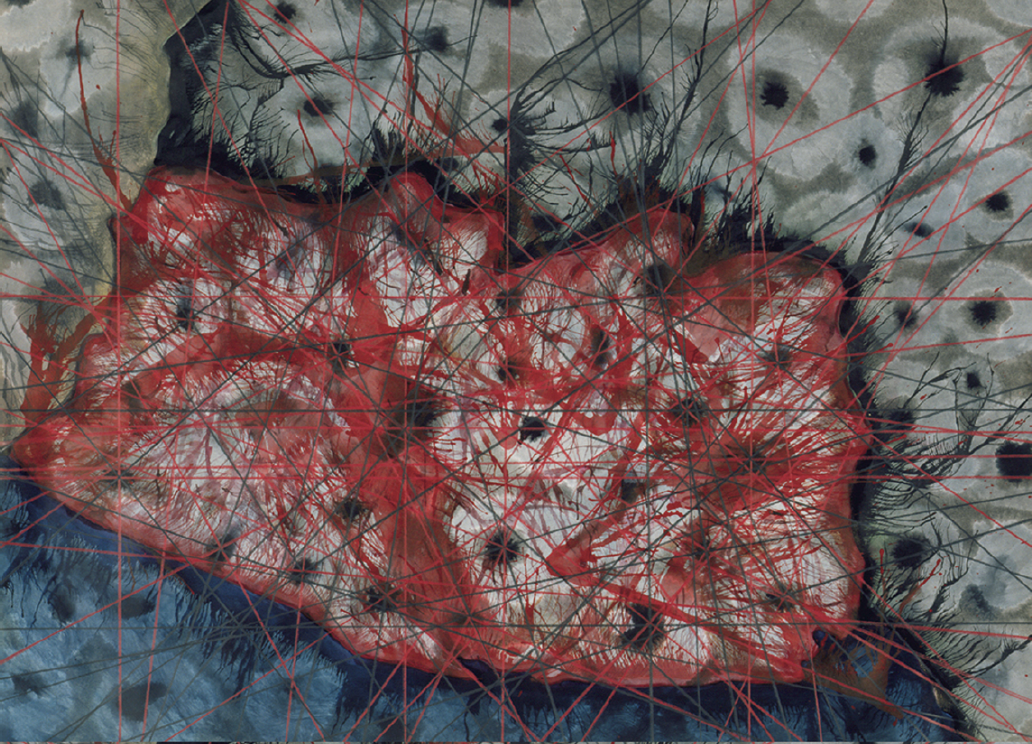

O’Hara slavick, who is also a socially inclined photographer, has chosen a labour-intensive technique for this series to emphasize her engagement with the subject matter; slowing down the process allowed more time for contemplation. Using watercolour, gouache, charcoal and ink, splattered, bled, dragged, washed, circled, traced, pin-pointed and inscribed upon Arches paper, the results are colourful to the point of cacophony. The formal elements shift dramatically between the linear and the organic, the grid and the gesture. While o’Hara slavick’s representations of shattered nations are abstract rather than figurative, they nevertheless index the vulnerability of human bodies. Her transcendental aerial views reflect the horrible awareness that, “as in war, civilians are rendered invisible.” The overwrought application of media and evident touch of the artist’s hand overcome the distance of the aerial perspective and its calculating cartographer’s vision. In some works, delicacy and deliberation are present in the patterns of dots that echo across the paper. In others, paint is shot or blown onto the surface to create spiderwebs, micro-explosions, and amoeba-like forms that creep over the paper and stain it. The unruliness of the materials reflects the imprecise trajectories of the bombs themselves (so frequently missing their targets).

O’Hara slavick’s references to skin and other easily wounded surfaces are achieved through an anthropomorphic genre that is both abstract and representational. The resemblance to skin lesions, metastasizing carcinomas or virulent cells viewed through a microscope alludes to the diseases that afflict victim populations (mostly children) over generations due to the pathogens introduced into the environment by such warfare (depleted uranium in the first Gulf War, for example). While o’Hara slavick mentions her admiration for Alfredo Jaar and Doris Salcedo, the contemporary artist who shows the closest conceptual kinship is perhaps Sophie Ristelhueber, whose “Fait” series (1992) of large colour photographs depicts—from aerial perspectives— the scarred, charred and pockmarked Kuwaiti desert after the first Persian Gulf War. Although both artists evoke the loss of human life through landscapes in ruins, o’Hara slavick’s project explicitly denounces US militarism; each work is contextualized by historical and bibliographic information included in the list of plates, critically detailing each bombing campaign.

elin o’Hara slavick, World Map, Protesting Cartography: Places the United States has Bombed, 1854– Ongoing, 1999–2006, mixed media on paper, 30 x 22”. Photo: North Carolina Museum of Art.

The issue of beauty will invariably be one of the first questions to arise in relation to o’Hara slavick’s work. Is it compatible with the subject matter? Such a question is not only polemical but also retrograde, as if it is necessary to return to the modernist developments of George Grosz, Otto Dix and Max Ernst, whose artwork suggests that the horror and obscenity of war be reflected in its subject matter and technique. Carol Mavor contributes a moving essay on the potential for “terrible beauty” in the haunting after-effects of war. Inspired by the complex temporalities and affective memories of Marcel Proust and Roland Barthes, Mavor brings sensitivity to her consideration of o’Hara slavick’s work and to themes of photographic traces, the losses of Japanese and American mothers, stolen childhoods and those scars that never heal, that cut through national and generational barriers. Mavor focuses on the Hiroshima bombing to point out the uncanny poetries between the material remains of war (especially clothing) and the art, films and photographic narratives that document it. She mentions the wildflowers that sprang up amid the ruins of the bombed city (their rampant growth spurred by radioactivity) and the shadowy presence of a seated figure whose body evaporated in the radiation blast to leave only a silhouette “photographed” on the steps of the city bank.

elin o’Hara slavick, El Salvador, 1980–1997, 1999– 2006, mixed media on paper, 30 x 22”. Photo: North Carolina Museum of Art.

This publication couldn’t be more timely or pertinent. While the United States is gearing to broker a fall peace agreement between Israelis and Palestinians, it is hypocritically offering massive arms deals to Israel as well as to Saudi Arabia and its oil-rich neighbours. The Bush administration has also deemed Iran’s Revolutionary Guard (a branch of the nation’s military) a terrorist group, an unprecedented linguistic turn that appears less to deter the country’s supply of arms to insurgents in Iraq than to be a prerequisite for air strikes on Tehran. “Air strikes” is a euphemism for the act of dropping bombs on sovereign states in the name of “deterrence,” generally under the auspices of peace, security, stability or prevention. This logic of defending military intervention (the “just war” rhetoric) is unconditionally rejected in Bomb After Bomb by the scope of o’Hara slavick’s “deplorable archive,” which is expansive geographically and historically, and by Howard Zinn’s foreword to the volume, which cogently argues against bombing campaigns. The force of Zinn’s voice comes from his credentials as the author of A People’s History of the United States and from his decorated career with the US Air Corps during World War II as a bombardier who regretfully experienced (or, more precisely, enacted) the very destruction that o’Hara slavick memorializes on paper.

The radical politics of Bomb After Bomb are anything but naïve. With lamentable irony, o’Hara slavick implicates herself as a “war-tax-paying citizen of the bombing nation” and questions the anti-democratic policies of the US while celebrating the freedom of expression and safety enjoyed there. This is an ambivalent outlook but, ultimately, a hopeful one. ■

Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography, elin o’Hara slavick, Milano: Edizione Charta, 2007, softcover, 112 pp, $34.95.

Andrea D. Fitzpatrick is an assistant professor in the history and theory of art at the University of Ottawa.