“Body: New Art from the UK”

Martin Boyce, Everything Goes Away in the End, 2004, private collection, New York. Photographs courtesy Oakville Galleries, Oakville.

The British Council, in an effort to expand the perception of contemporary British art outside the UK, has been placing a much-needed finer point on the Young British Artist phenomenon of the 1990s. A number of thematic exhibitions have travelled abroad, the latest of which is “Body: New Art from the UK.” Bruce Grenville of the Vancouver Art Gallery and Colin Ledwith of the British Council have brought together 12 works that explore notions of identity in relation to physical form. In his book The Body and Society, Bryan S. Turner argues that, due to a shift in societal structure, our sense of identity in a postindustrial society is floundering. Once tied to marriage, family and property, relationships are now based on expectations of personal satisfaction; thus the body as locus for identity has evolved from a feminist concern into one that is less gender-specific. Nonetheless, 9 of the 12 works are by women.

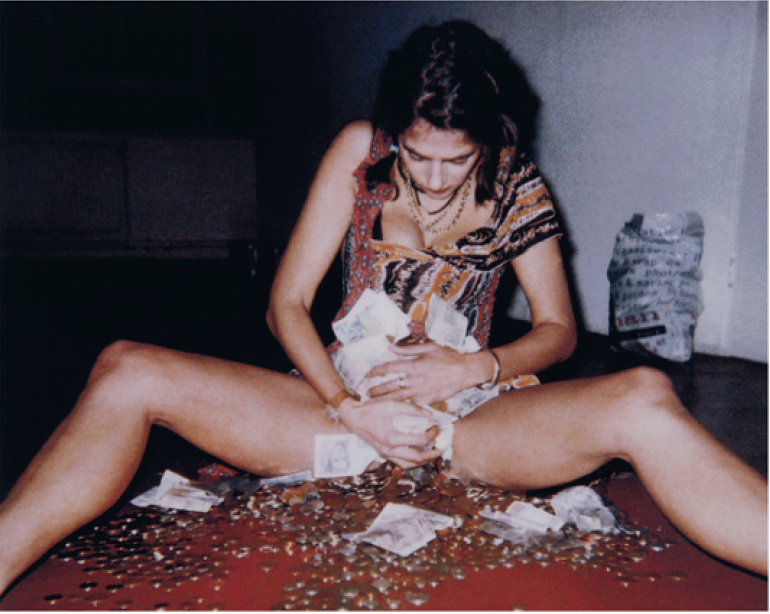

At Oakville Galleries’ Gairloch Gardens, Gillian Wearing’s video Homage to the Woman the Bandaged Face Who I Saw Yesterday Down Walworth Road becomes an experiment wherein the artist (and the camera, and, therefore, the viewer) assumes the woman’s identity, subject to the stares of passers-by on the streets of London. A similar identification between artist and viewer occurs at the other end of the gallery in Carey Young’s video I am a Revolutionary. This work depicts the artist in an empty office being repeatedly coached on the delivery of the line “I am a revolutionary.” The resulting disconnection between meaning and speaker ricochets off the viewer. Three of Rebecca Warren’s sculptures occupy the next room. Though rigorously modelled, the pieces bear little resemblance to anything other than what they are, two heavily fingerprinted masses of exceptionally fragile clay, and one large bronze. In the context of the body, the sculptures are best seen as an installation where strength and fragility play off one another. On the opposite wall, a quilt and a large colour photograph by Tracey Emin each depict the artist crudely sprawled, a stream of glittering coins flowing from between her legs. By evoking childbirth, menstruation and the results of a winning pull on a slot machine, Emin equates monetary value with procreative value, identifying her body as a vessel, her sense of self as fragile as Warren’s unfired sculptures. The body in these works is defiant, though delicate and incomplete.

Tracey Emin, I’ve Got It All, 2000. Courtesy the artist and Jay Jopling / White Cube, London.

The exhibition continues in Oakville Galleries’ Centennial Square with two photographs by Cornelia Parker. Marks made by Freud, subconsciously is a close-up photograph of Sigmund Freud’s worn leather armchair. Shared Fate (Oliver) depicts a doll sliced in two by the same guillotine that beheaded Marie Antoinette. While both photographs refer obliquely to the body, Parker’s work calls on the viewer to complete a historical moment; likewise, Tacita Dean’s film Mario Mertz, a 2002 portrait of the aging artist. At times content, irritated and bored, Mertz’s occasional chatter is obscured by the loud clicking of the film projector in the viewing space. A sculpture by Cathy Wilkes is comprised of a mattress upon which are strewn an upside-down tea tray and some slender pieces of wood. Two text paintings reading “Our Misfortune” and “Photographed by Dorothea L” decorate the wall above. The installation barely suggests a body, and the only clues are the paintings, which refer to the depression-era photographs of Dorothea Lange. Sarah Lucas’s Bunny Gets Snookered #4 is an abstracted soft sculpture of a rabbit-like figure propped on a chair, the torso reduced to the gusset of a pair of stockings. Each of these works presents an enigmatic, deliberate body, again physically incomplete.

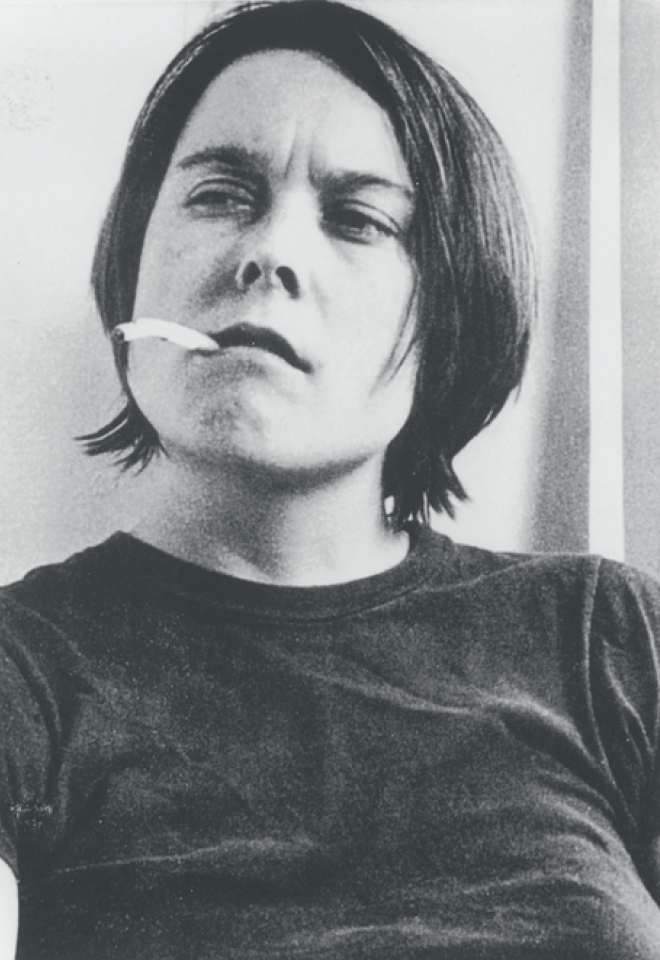

A suite of 12 self-portraits by Lucas marks a turning point in the show. She engages in various confrontational positions, holding a large fish in Got a Salmon on #3, sitting naked on the loo in Human Toilet II. Using her body to represent male and female aspects of sexuality, she proposes identity as a conflation of opposing factors.

Sarah Lucas, Fighting Fire with Fire, 1996, from “Self-Portraits, 1990–98, 1999.” Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

The three male artists in the exhibition are working in a similar fashion. Twenty-one black and white wall drawings by Jake and Dinos Chapman, from a series entitled “My Giant Colouring Book,” are partially completed colouring book pages to which the artists have added their own embellishments, often of macabre, disembodied figures. If the completed pictures represent the body as a whole, they have been clearly divided into opposing perspectives—innocent and knowing, good and evil. Martin Boyce’s sculpture Everything Goes Away in the End transforms parts of modernist furniture into a Calder-like sculpture. His sorbetcoloured abstract paintings on the wall behind are identical but for the fact that the second one has faded. The time lapse suggested here reoccurs between two of Douglas Gordon’s videos. In the first, The Left Hand Doesn’t Care what the Right Hand Isn’t Doing, one hand is shaving the other. In The Right Hand Doesn’t Care what the Left Hand Isn’t Doing, one hand colours the other with a black marker. The fact that both hands presumably belong to the same body echoes good and evil, us and the other, in Chapman’s work.

Gordon’s shockingly stark work is arguably the most powerful elucidation of Bryan Turner’s notion of the “Somatic society,” wherein major political and moral problems are expressed through the human body. His suggestion that, today, relationships are based on expectations of personal satisfaction gained through social contact helps to clarify the defiant narcissism, body-consciousness and awareness of social codes evidenced by the Young British Artists. The exhibition elegantly concludes with Sam Taylor Wood’s Five Revolutionary Seconds VI. This is a photograph covering an entire wall, and the viewer walks its length as five different scenes unfold to a soundtrack, bringing a self-awareness to the act of surveying the isolated characters within. ■

“Body: New Art from the UK” was exhibited at Oakville Galleries in Oakville, Ontario, from April 8 to May 28, 2006, and will travel to the Edmonton Art Gallery, followed by the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Andrea Carson writes on contemporary art, architecture and design. She is based in Toronto, from where she publishes the international e-newsletter View on Canadian Art.