“Bilocation”

Chad Oakenfold, Gene- Brynner, 2008, still from video installation. Images courtesy LES Gallery, Vancouver.

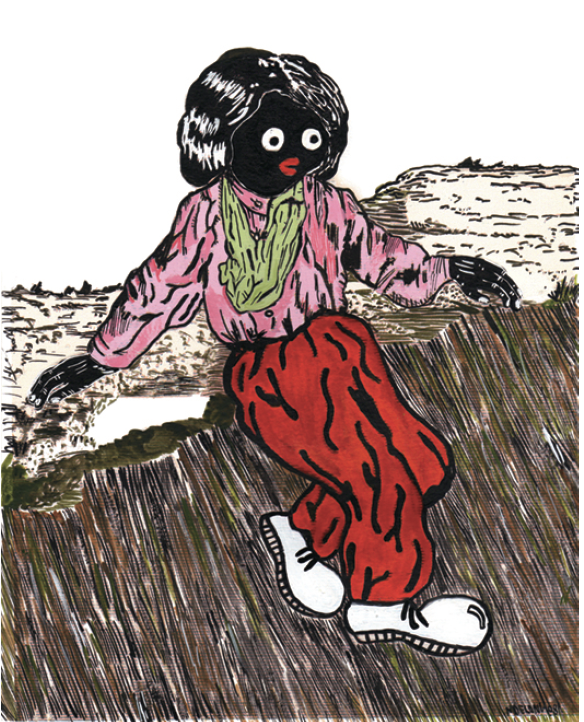

“Bilocation” was the title given to a series of three separate exhibitions that ran over a period of six weeks through the months of April and May of 2008 at the Lower East Side Gallery in Vancouver, BC. In each show two artists faced off, one showing on each side of the gallery. Something like a doppelganger, or the ability to be in two places at once, or the condition of being split from one’s self, “Bilocation” is a decent neologism invented by the gallery for the purpose of the show. In each, the curators paired a Vancouver artist with an international artist whose work shared some common ground in style, format or construction— evidence of bilocation. The first and second show featured collage and drawings: Joseph Hart from New York with local Mark Delong; Manuel Olias from Valencia, Spain, and James Whitman. In the third, Vancouverite Chad Oakenfold was paired with Genevan brothers Gregory and Cyril Chapuisat, who enlarged the concept of a mouse hole so gallery visitors could (and did) scuttle around in tunnels behind the walls of the gallery. All three “Bilocation” shows were spectacular and strange, and the artists all showed impeccable control over their styles—disciplined and detailed, clearly the result of hours of slavish commitment, work that supports long readings and due thought, and an intervention that without a doubt irreversibly changed everyone who underwent the experience. In the first show Joseph Hart’s and Mark Delong’s collages were compared. Despite evidence of bilocation, their only obvious resemblance lies in the fact that both artists create a patchwork quilt of mixed media using printed matter, paint, ink and pencil. Hart’s work is more abstract, with a style somewhere between Joan Miró and Saul Steinberg, representations of the inner and outer cosmos. Delong is furiously creative, and from his large body of work, LES chose a series of recent collages that feature a Guston-like alter ego, a wiener-nosed character in humongous red pants. Delong’s large-scale pieces are based on massive digital files he prints out in pieces and glues back together. One is an abstract, quasi-blurred piece, and the other features a sad rabbit with elephant skin, hiding his face behind great wrinkly, grey lop ears. Delong recently launched a massive book with TV Books, New York photographer Tim Barber’s new publishing line, and he regularly proves he’s one of Vancouver’s most audacious artists.

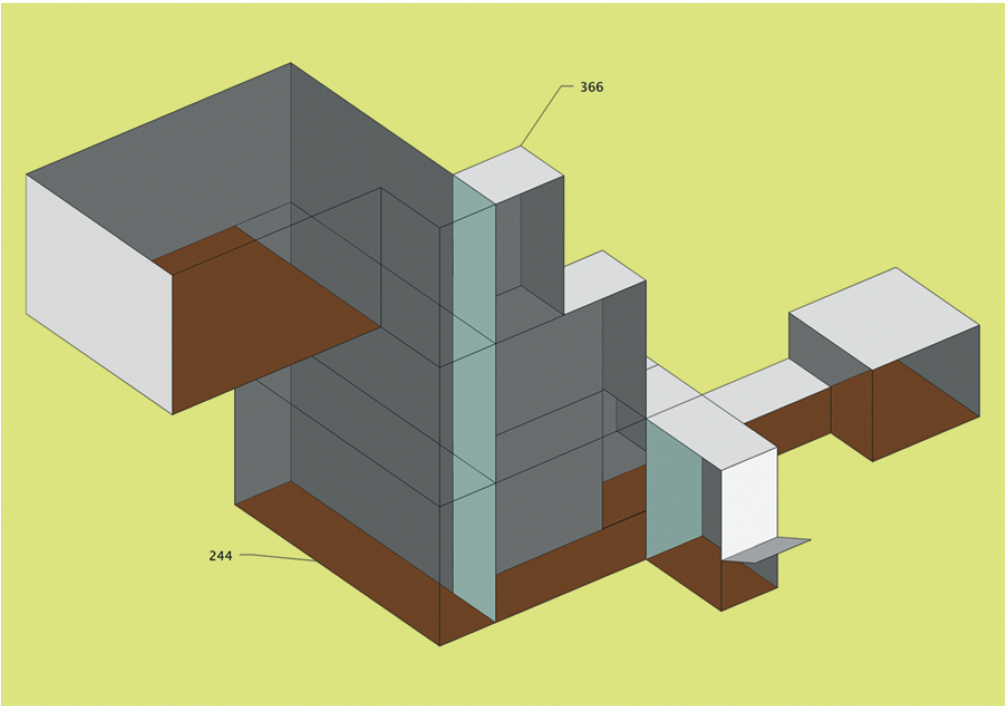

Gregory and Cyril Chapusiat, Digital Sketch, 2008.

Joseph Hart, Untitled, 2007, collaged paper, ink, acrylic and graphite on paper.

The second show singled out graphite on paper. James Whitman works with an obsessively sharpened point, laying down landscapes like fine mesh, creating biomorphic trematodes, marbling patterns, and mutant anatomical cross-sections. Manuel Olias’s work is more figurative than Whitman’s. Ed Pien might be another example of Olias’s bilocation. Olias’s uninhibited human distortions divine a sexual heat from the slender pencil line that Whitman uses scientifically. In the third and final show, local Oakenfold presented Gene/Brynner, a video projection. It’s a mash-up of sorts. Oakenfold stole a postmodern remake of the film Singin’ in the Rain, using the eponymous scene used for a Volkswagen Golf GT commercial. The commercial digitally masked Gene Kelly’s face over the umbrella-toting breakdancer who shot the remake. Oakenfold removes Gene’s face again and replaces it with the glowing, bald head of Yul Brynner. This is an example of a piece of art that only makes sense in the context of a show about duality and repetition. The video was a skewed and brilliant match with the Chapuisat catacomb. At the opening of the third show, a friend of mine who went through the Chapuisat tunnels came out red faced 25 minutes later and said that it put him in touch with his “most primal fears”—not your usual opening night reaction. The Chapuisats have built these fallopian structures in other galleries, and my friend’s harrowingly pleasurable experience seems to be the intention. You generally enter through an unassuming hole built into a wall or ceiling. At the Neue Kunsthalle in St. Gallen, they built a 200-square-metre cardboard “burrow,” or as the brothers also call it, a “subterranean assault course.” The installation is demanding on the viewer both psychologically and physically. The concept is almost cruel (to neurotics especially), but very affecting. At the LES the entrance was underneath the counter. You had to wear a headlamp, like a coal miner. From under the counter you squirmed around a tight left corner—I cannot stress enough how tight that first corner was—up and into the walls, where apparently—the first corner jogged enough primal fears in me that the rest of the catacomb was left to others to tell me about— narrow passages finally led to a small, hot little alcove above the bathroom where children’s paints and paper were set out to keep you busy while you rested before the labouriously claustrophobic return trip. The penetration of the space was a psychic and physical challenge to the viewers, much like German artist Gregor Schneider’s Dead House, a nightmare conversion of his own home, ongoing since 1985, which is now an unknown, mutable and unconventional space full of secret rooms, airless corridors and claustrophobic spaces, all of which should remind us of provisional prisons, horror dungeons and domestic abuse. The Chapuisats have done the same with tunnels as Schneider has with rooms. In addition to the show, LES printed a catalogue. The introductory essay addresses the difference between imitation and duality. “Lisa Giroday (proprietor of the LES Gallery) came up with the idea of manipulating the German word doppelganger to express the segregation and isolation that the Vancouver cultural scene can manifest.” Writer Jesse Scott cites photo-conceptualist tall poppies Jeff Wall and Ken Lum in his essay. “Bilocation’s” catalogue proposes that an artist is better to have an unexpected doppelganger in New York or Spain than to consciously derive their technique and content based on close readings of local art history and the work of their Vancouver predecessors. The six artists in “Bilocation” were more unalike than alike, more unique than derivative, but presented in sets of two, it’s true they showed unmistakable similarities. There is some symmetry between the concept of bilocation and happenstance. Still, the gallery’s passionate call for individuality is well heeded. Instead of basing their show on work full of local references, these art mates were brought together on a whim and a plan by a striving, artistrun commercial gallery willing to contradict prevailing tendencies. “Bilocation’s” curatorial position, if not the opinions of the very talented artists within, is meant to express a heated opposition to the institutionalized artist-run culture that has become, in Scott’s words “parallel to the institutions they were once perpendicular to, having copulated and coagulated with them, at several obtuse and obscene angles.” ■

Mark DeLong, Running Man Winter, 2008, inkjet and acrylic on paper.

“Bilocation,” a series of three exhibitions, was exhibited at LES Gallery in Vancouver from April 12 to June 14, 2008.

Lee Henderson is a Contributing Editor to Border Crossings.