Bharti Kher

The international arc of Bharti Kher’s career in some ways describes a reverse migration—although not necessarily an intentional one. Born in London, England, she earned a BFA in painting at Newcastle Polytechnic before making a life-transforming journey to India, her parents’ homeland, at the age of 22. She stayed there, her reasons having much to do with matters of the heart, an organ she has hyperbolized in her art; shortly after arriving in India, Kher fell in love with and married Indian artist Subodh Gupta. Many years later, An absence of assignable cause, Kher’s life-size resin sculpture of a blue sperm whale heart—the largest heart in the world, possessed by the world’s largest creature— serves as a metaphor for the vastly irrational and inexpressible power of love.

Bharti Kher, An absence of assignable cause, 2007, bindis, resin. Photo: Bharti Kher Studio. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Perrotin and the Vancouver Art Gallery.

In all its colour and clamour and sensory bombardment, India also filled Kher with excitement, and she draws significant forms and materials from its life and culture. She has made sculptures that allude to its ancient beliefs and myths (such as that of the beheaded, blood-spurting, fertility-begetting Tantric goddess Chinnamista) and that depict its contemporary outsiders (such as middle-aged prostitutes from the red-light district of Kolkata). Her sculptures also incorporate found objects, images and materials of South Asian manufacture, from wooden ladders to silk saris. Still, Kher’s practice speaks to an international audience because she has the ability to universalize the particular. It also speaks to an enduring feminism and to the post-colonial and post-modern cross-fertilization of cultures. Kher incorporates references to European as well as Asian art history and to contemporary art’s globalized concerns.

Her universalizing connection to India is also evident in the creative and highly individualistic claim she has laid to the bindi, the coloured forehead dot that in the past symbolized the third eye and also signified a woman’s marital status, but that is now mass-manufactured in die-cut felt and used primarily as a decorative accessory. Kher employs uncountable thousands of bindis as if they were paint. With this material, customized in a range of unexpected colours and sizes, she produces large abstractions on board and dazzling and complex patterns across shattered mirrors, vintage medical charts, glass-fronted cabinets, and resin sculptures (including her sperm whale heart). When applied to certain surfaces or images en masse, the bindis may suggest celestial charts or topographical maps—or become a kind of organic tissue or integument.

Bharti Kher, The Messenger, 2012, resin, sari, wooden rake, granite. Photo: Genevieve Hanson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

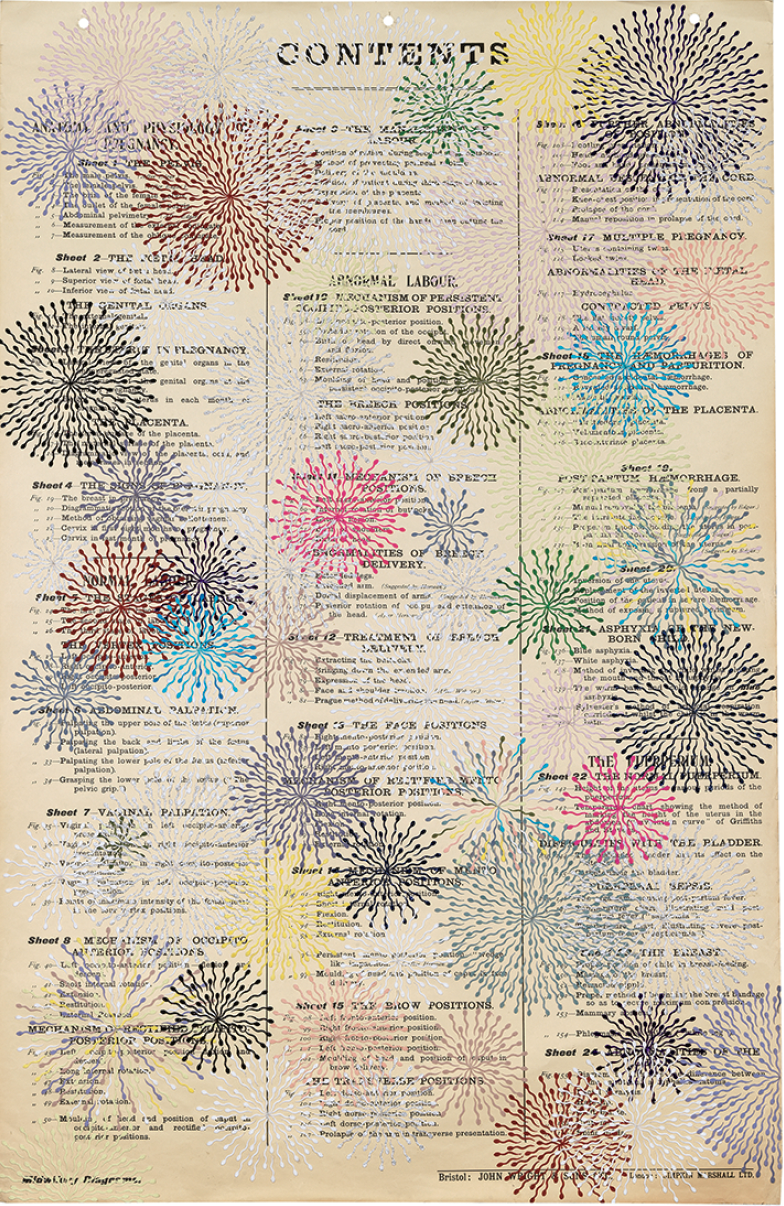

All these possibilities are seen in Contents, based on vintage medical charts of abnormal labour and delivery. Over the technical words and images—devised by men, concerning women—Kher has applied complex patterns of sperm-like bindis. This particular shape of bindi, a dot with a wiggly tail, is manufactured in India to represent a snake. In Kher’s work, however, its massed forms read as swarms of sperm, aggregating into swirling patterns or swimming frantically towards or away from a central and seemingly contested point. They could be symbols of sexual energy and procreation, or of domination and colonization.

The bindis may also suggest an idea of healing: thousands of tiny bandages adhered to and often obscuring jagged networks of wounds and fractures. In “Matter,” Kher has smashed the surfaces of four large mirrors and then “repaired” them with intricate patterns that evoke chrysanthemums, fireworks, swirling constellations of distant stars. In fairy tales, myths and art, mirrors have long been symbolically charged objects, often associated with female beauty, as Daina Augaitis points out in the exhibition catalogue. If broken, they forecast bad luck or the loss of magical power. In more recent psychoanalytic theory, the mirror plays a role in the construction of individual identity. Using bindis, Kher redresses a number of these associations to suggest an empowering and almost alchemical act of transformation. “Matter” challenges tradition and superstition, posing the possibility of breaking out of a conditioned way of thinking and becoming, instead, something complex, gorgeous, not entirely resolved perhaps, but not imprisoned by social or cultural circumstance, either.

Some of Kher’s most powerful works manifest her enduring interest in biology and morphology, sexuality and gender, transgression and metamorphosis. Her 2004 series of digital colour photographs established her thematic claim to hybridity: here, seemingly female figures have been morphed with animal heads, hooves and fur, and also with attributes of the human male. Such images foreground our kinship with the animal world— both the DNA we share with the other creatures that inhabit this planet and the fine line that exists between the “civilized” and the “savage”—while again defying socially mandated gender roles and their political and economic ramifications. (A couple of the prints include vacuum cleaners, themselves in a state of transformation.)

Bharti Kher, Contents, 2010, bindis on twenty-one medical charts. Private collection. Photo: Mike Bruce. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

A series of “goddess” sculptures, created between 2008 and 2012, are powerfully three-dimensional expressions of these earlier ideas of morphology, hybridity and transformation. Cast in resin from slightly androgynous looking female models, they grapple with the kinds of animal-human transformations common to myths and legends throughout the world. Often, however, their animal attributes are burdensome or comical, irreconcilable with their human condition. The accessories of civilization are equally unlikely. One figure bears a winding tail composed of sari fabric, another, long, ungainly antlers. Two of the figures are armed with wooden rakes; another bears a large banana leaf as a shield. A gold and black figure, Lady with an Ermine peers through the sharp tines of a rake, whose handle is adorned with a fur muff at crotch level. The figure is naked except for her conical, granite headpiece, on which are balanced a stack of china cups and saucers.

The title of this work is borrowed from that of Leonardo da Vinci’s late 15th-century portrait of Cecilia Gallerani, mistress of his patron at the time, Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. In the Leonardo work, the “lady” holds an ermine, a wild creature, long and slinky, domesticated as a pet. Gallerani’s hair is domesticated, too. Smoothly and tightly wrapped around her head and under her chin like a close-fitting cap, it conforms to an odd fashion that again suggests the taming of the natural and the sexual. Although Kher’s sculpture in no way resembles the Leonardo painting, it seems to pose similar and again, irreconcilable oppositions. Kher’s art unsettles us in amusing, absurd and frightening ways—and that is as it should be. ❚

“Matter” was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from July 9 to October 10, 2016.

Robin Laurence is a Vancouver-based writer, curator and contributing editor to Border Crossings.