Beyond Cinema: The Art of Projection Films, Videos and Installations from 1963-2005

It is hard to imagine that only 30 years ago, John Szarkowski’s presentation of William Eggleston’s photographs at the Museum of Modern Art would have been considered a breakthrough because they were in colour. By separating lens-based imagery from the 19th-century notion of fine art to which the black and white photograph had been, up to that point, confined, MOMA—a key player in the creation of the very idea of modern art—expanded the definition of art to include contemporary production. Doing this, they opened the door to, among other things, works in new media. Arguably, it is this event, rather than work done in structural film, that augured the current dominance of video installation in contemporary art. It points to the growing importance of the institution itself. This is especially true of work on video. If Duchamp had critiqued the artwork’s institutional dependence a prescient 90-odd years before, the triumph of video installation as an art form represents its wholesale consolidation; the two cannot be separated.

Functioning as a companion piece to, and update of, the Whitney Museum’s 2002 exhibition about the projected image, “Into the Light: Image in American art 1964–1977,” “Beyond Cinema” presents 27 works designated as markers along the road to video’s present supremacy. The focus of both shows is the art form’s basic technical requirement of projection as a stepping-off point for the creation of a spatial experience in the gallery, whether perceptual or psychological and usually a combination of the two. Video’s ability to be projected from the rear, as opposed to film’s frontal orientation, adds an extra dimension to this dynamic. The exhibition does an excellent job of showing the different ways artists have devised to think through the permutations of this possibility.

Pipilotte Rist, Ever Is Over All, 1997. Photo: Alexander Troeler. Installation view at Kusthalle Zurich, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Werth, Zurichhoriden. Photos courtesy Kamburger Bahnhof.

Edge of a Wood, 1999, a ravishing installation by Rodney Graham, opens the show and suggests its emphasis. While early video art was once valued for its anti-aesthetic austerity, Graham’s work has a shimmering, painterly lushness. On a two-screen projection, to the deafening sound of the chopper’s blades, helicoptermounted searchlights illuminate trees at the edge of the forest. With this simple but gorgeous update on the genre of landscape painting, Graham implies that art may change in keeping with technological developments but its focus stays the same: the world and the complicated business of how we see it.

Graham’s work creates a threshold for the viewer’s entry into the exhibition—this is especially true due to the enveloping nature of its soundtrack—suggesting that the prevalence of video projection in art is only a reflection of the immersion of our culture in a mediated world. Douglas Gordon’s 24-hour Psycho, 1993, is well served in this context. The artist’s slowing down of Hitchcock’s film to a molasses pace looks today less like a neat trick than a statement of millennial significance. The dream—and the nightmare—of our mediated lives has no beginning or end.

Monica Bonvicini, Destroy She Said, 1998. Photo: Ruth Clark, courtesy the artist and Galleria Erni Fontana.

On a lower level of the venue, Diana Thater’s The Best Space is Deep Space, 1998, encapsulates this idea in a dazzling, four-part installation. An image of a white horse and her handlers standing in a ring is seen through the haze of dry ice and a changing array of coloured spotlights. Variations of this scene are repeated in two large-screen projections and on a monitor placed on the floor: viewers see what the cameras see and see the crew filming this in a shot from behind their backs. As the coloured gels change from pink to yellow to blue, the horse appears and disappears, and, on another monitor, alphabet fridge magnets in primary colours spell out the production credits against a white background. The installation acts like an object lesson in the persuasive authority of the image. For all of Thater’s efforts to break down the illusion, its powers of mystification remain no less profound.

Another stunning work, Monica Bonvicini’s Destroy She Said, 1998, uses repetition and dissonance to fracture the space of filmic artifice. On an angled two-screen projection with the wooden grid of its support sticking out on all sides, the artist presents clips of European film stars, such as Anna Karina and Monica Vitti, in a variety of fraught cinematic moments. On the audio track we hear a woman crying, a phone ringing, a plane travelling overhead, the sounds sometimes in sync with the image but mostly not. When, in this montage of distress, a woman shoots a gun, the repertoire of dramatic effects is complete, the artist suggesting that, at least as far as cinema is concerned, the psychological space of femininity is dangerously overwrought.

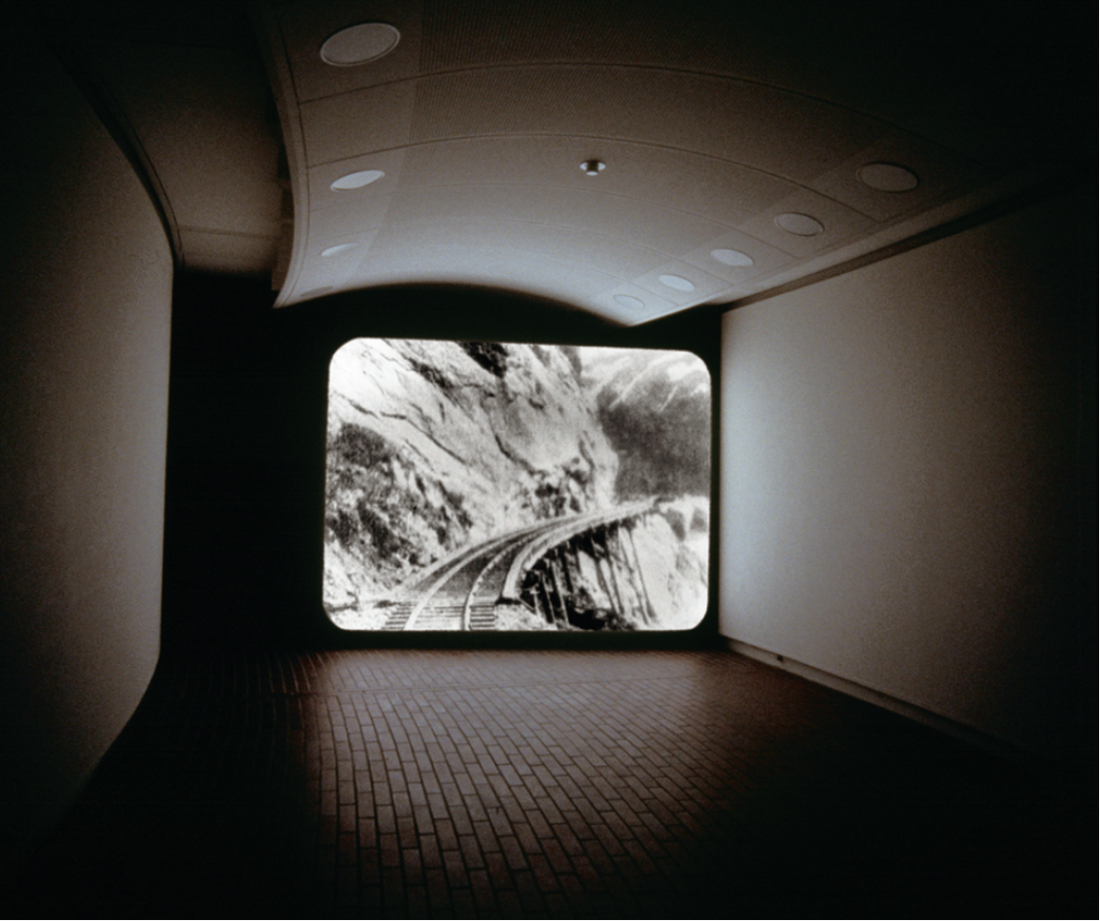

Stan Douglas, Overture, 1986. Photo courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York.

Toronto artist John Massey’s seminal As the Hammer Strikes (A Partial Illustration), 1982, offers a kind of masculine counterpart to Bonvicini’s work. In a three-channel installation in black and white and colour, the artist drives a car on the highway in the desolate Canadian winter. As he converses with a hitchhiker he has picked up, the screens alternate between images of the landscape, the driver and his passenger, and stock footage shots of the things they talk about. Because the hitchhiker speaks with a slight stutter, the conversation is somewhat stilted, and this impression is reinforced by the image montage. When the passenger talks about being at a strip bar and we simultaneously see the image of a stripper on an adjacent screen, it creates a strangely hollow feeling, as if the speaker had no interiority. A little-seen example of video projection in its early form, as a critique of mediated subjectivity, the work is devastatingly effective.

For Canadians, “Beyond Cinema” is a watershed for two reasons. Of a curatorial team of four, two are from Canada, the artist Stan Douglas and Christopher Eamon, curator of the San Francisco- based Kramlich collection, one of the largest and most important private collections of media art. The duo’s involvement and the strong presence of Canadian artists in the show attest to the leading role Canadians have played in the development of this art form (Douglas is represented in the show with his magnificent 1986 work, Overture.) A crucial acknowledgement of this contribution, “The Art of Projection” may also represent a turning point in Canada’s ability—or willingness— to sponsor its artists internationally. Beginning April 1, 2007, the Harper government has allotted a budget of exactly zero dollars to its missions abroad for the promotion of Canadian culture. This, from a federal government that the October 25 Globe and Mail reported was “awash in surplus cash.” There is more at stake here than the careers of Canadian cultural producers abroad. It is not much of an exaggeration to say that a government so unaccountably hostile to the arts portends a dark future for the country. ■

“Beyond Cinema: The Art of Projection Films, Videos and Installations from 1963–2005,” curated by Stan Douglas, Christopher Eamon, Gabriele Knapstein and Joachim Jäger, was exhibited at Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin from September 29, 2006, to February 25, 2007.

Rosemary Heather is the editor of C magazine.