Beth Stuart: Rapture Rupture Raptor

The newness of Beth Stuart’s art results in my growing almost irresponsibly adjectival. Words flow at their own behest from my fingers onto the keyboard, get lodged in a writing-program (the ecriture-creature), are stored in my word-hoard-hard-drive, then bob up later like corks on a sea of consciousness.

Her art is winsome, which is to say, charming, seductive, beckoning and lonesome, isolated in the shrill air of its inventiveness. The work unhinged me directly into a tumble of pun and wordplay: you winsome, you losesome, you are loansome—what is owed this work? It is lithesome, “the lithesome panther moved effortlessly and noiselessly through the rainforest” [of contemporaneity], intones the Merriam-Webster online dictionary, being helpful about the word “lithesome.” And to be honest, the more you see of Stuart’s work, the more you slowly grow personally, fleshedly somatic, as you watch your certainties braiding away into the distance.

“Heddle and Reed” (detail), 2010

All meaningful art, like Stuart’s, begins in tendentiousness. She thinks a lot; she says, in an artist’s statement from February of 2012, “about the relationship between texts and bodies, between reading and sex…I think about gender, and ethics, and modesty,” she writes, “and minor things like moving liquid round on a surface with [a] hairy stick. I think about what it means to negotiate, to come together, rather than to set against, to argue or to conflict. I think about vagaries, discomfort, awkwardness and un-nameabilty.”

Rapture/rupture/raptor: some of Stuart’s exhibition “what bonds are these?” at La Centrale in Montreal in the spring of 2012 evoked rapture. Is there anything more exquisite, for example, than her pink-blush painting/construction work, (Varvara Stepanova) from that show—evanescent, rose-stained soap-bubble-shape utterances, “text and bodies.” Paired with it and supported on a creamy rectangle of linen is another painting, work, (Jack Bush), with some of its weft removed and then “spranged” (more about “spranging” shortly), their ephemerality fixed, grommeted in place. Much of that exhibition evoked, at the same time, rupture—in Stuart’s loosing her inner-raptor (from the Latin word, rapere, to seize or take by force, to carry off) into the chicken yard of most received ideas concerning late-modernist painting and object-making.

“work (Jack Bush)”, 2012, commercial painter’s linen, weft partially removed and warp spranged, gesso, acrylic, paint, grommets, hanging hardware. “work, (Varvara Stepanova)”, 2012, acrylic and water media on canvas, grommets, hanging hardware. Courtesy the artist.

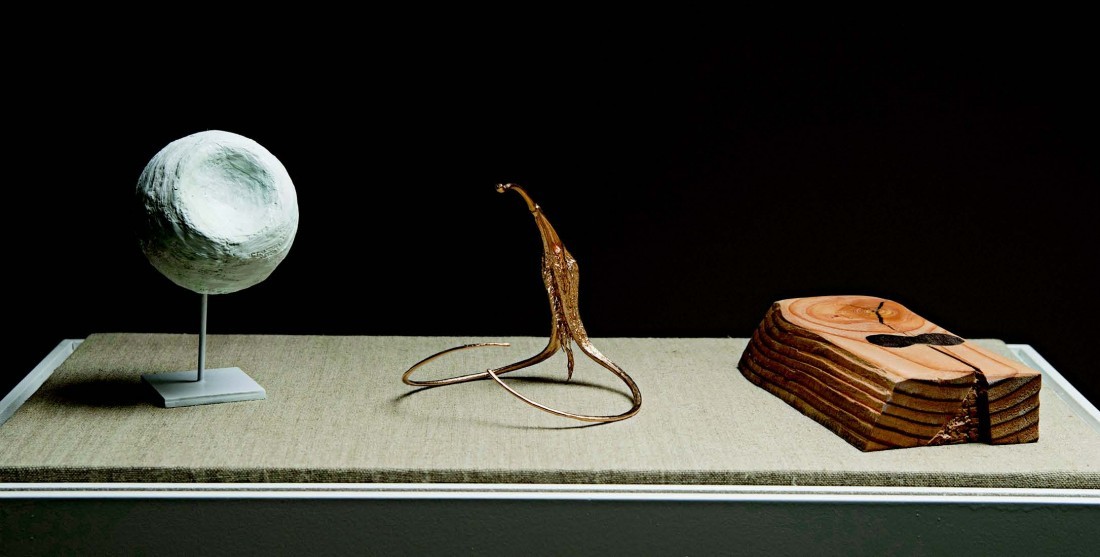

While Stuart and I were talking a few weeks ago and looking at some of her pieces I casually rested my hand on a nearby plinth and found myself suddenly both discomfited and enraptured (seized by both rapture and by the prickly inner-raptor of alarm) by having placed my hand almost directly upon a small, gold-plated sculpture of what could be a standing insect. The gleaming insect-plant bears the name Georges, not because it might be cute to call a small, tabletop-sized, gold-plated cast-bronze sculpture Georges, but because the piece is part of a tiny trilogy of named objects—the Amuse-Bouches sculptures. The three objects are called Paul, Georges and Marguerite. They are from 2010, from the “two sticks in a shed” exhibition. Even little objects can have immanence. When you stand up close to a meaningful, meaning-filled small object, even, in my case, inadvertently, the thing rears up to embody a certain giganticism. “Think of the space in front of the body,” writes poet Cole Swensen in The Book of a Hundred Hands (University of Iowa Press, 2005). “You can’t walk in. You can’t find the door. We call it the present.” There’s no space like the present.

Georges began as a plant called Devil’s Claw, also known, because of its central pod, its hooks and its wavy, tenticular extensions, as the Grapple Plant or Wood Spider. As a healing plant, it is used to treat inflammation and conditions like osteoarthritis. As a spooky little sculpture by Beth Stuart, however, it has become the representation of one of the three characters—all writer-artists—around whom Stuart has expertly woven a brilliant, highly ambitious short play, Joinery:Menuiserie, 2011, handsomely published by Battat Contemporary, in pamphlet form, as companion to the exhibition “two sticks in a shed.”

“Amuses Bouche (Paul, Georges, and Marguerite)”, 2010, brass, cedar, encaustic; rose-gold plated bronze; fir, walnut. Courtesy Battat Contemporary.

Stuart has not composed Joinery:Menuiserie so much as she has contrived it, selecting, with exquisite care and tact, the three voices that make up the play—Reason, Love and The Soul—from texts by Paul Klee (Reason), from his On Modern Art, by French 12th century mystic Marguerite Porete (Love), from her The Mirror of Simple Souls and by Georges Bataille (The Soul), from his infamous Story of the Eye—a heady and ornate trilogy of voices. It is both funny and moving to encounter these three monologues juxtaposed because the three character/voices, though powerfully present to one another, never really interact. Three Solitudes. At least they do not directly interact. But they do mediate one another, lend one another colouration and depth:

Reason: This shows a remarkable intermixture of our quantities and it is only logical that the same high order should be shown in the clarity with which they are used. It is possible to produce quite enough combinations as it is.

The Soul (smiling to the audience): That was the period when Simone developed a mania for breaking eggs with her ass.

Love: No, not at all, for Souls such as she possess the Virtues better than any other creature, but they do not make use of them.

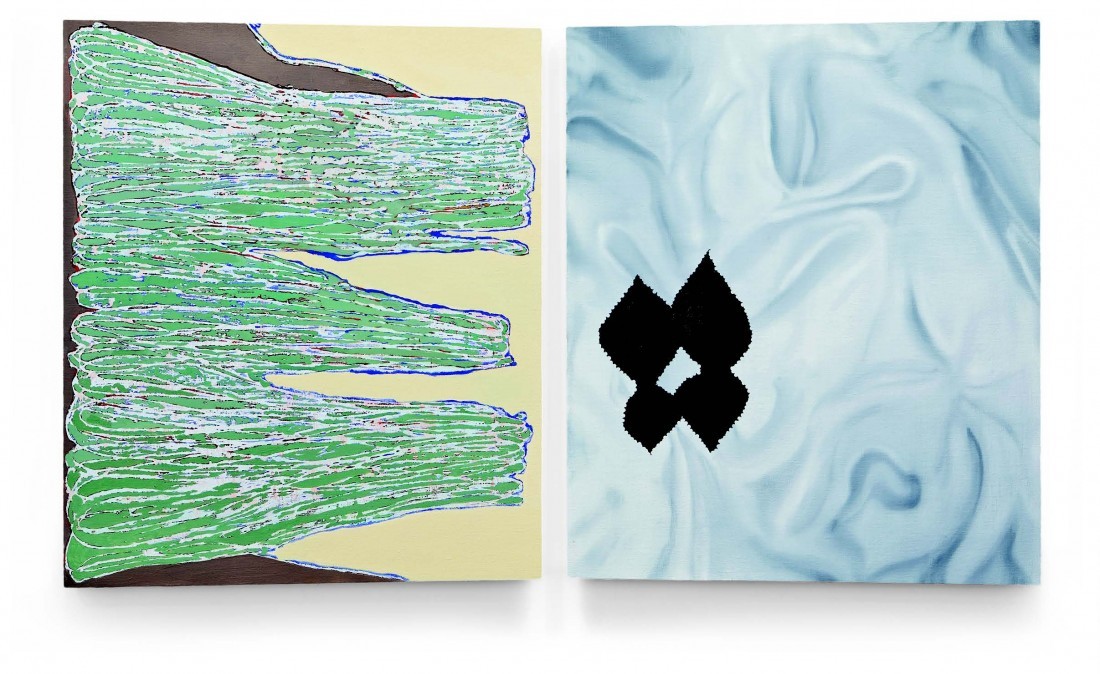

“Doppelbanger 04 & 05”, 2011, oil on linen panel. Courtesy Erin Stump Projects.

Doppelbanger is a 2011 series from a body of work titled “the cliques.” “Doppelbanger” is a truly delicious pun, and functions as a remarkably concise way of referring to paired works that do not echo or replicate one another, as doppelgangers might but impinge upon one another, and which meet, as a statement from Stuart’s Toronto gallery, Erin Stump Projects (ESP) puts it, “in conversational resonance,” two paintings that “speak without arguing.” Here is one form of the playing-out of the “negotiation” Stuart spoke about. In Doppelbanger 04 and 05—one of my favourites of her pictorial jostlings, where the objects run against one another “inciting friction and forgiveness”—one picture posits three peninsula-like, fingering extensions of variegated green on a pale hospital-corridor yellow ground, with supporting rivulets of chocolate brown, set up beside an adjacent work where a pair of rather frayed black, crisply-painted shapes of eccentric mien float upon a ground of pale, bluish drapery—which, for some reason, seems more horizontally disposed than vertically and therefore looks less like drapery than bedding. This, I know, sounds fanciful, even irrational.

In Doppelbanger 12 and 13, a pinkish-grey, rather fleshly wall of what looks a bit like rubber bricks—in the woozy shape of an unstable tower (see how we seek recourse to familiar imagery)—stands on a thin wedge of red-orange, with two maddening little coloured disks hovering, like escaped balloons, on a wan turquoise ground. This essentially insipid drama is answered, or at least commented upon, in the work on the right, by a big, blowsy, shaky, chocolaty orange-brown oval riding none-too-authoritatively on a sunny yellow field. These pictures might be less likable if they weren’t so absorbing. All the “Doppelbanger” pictures take us directly to Stuart’s ruminations, in her statement of February 2012, on the figure-ground enigma: “I think a lot about the relationship of the figure and the ground…I think about what it means to interrupt, to disturb, to perturb the figure ground relationship on a level of perception, of feeling….” Texts and bodies. Reading and sex. Negotiation. At what a prodigious distance from the sweaty, imperative ideals of Modernism these consciousness-nurturing objects are sited. And at what a lonely, untethered spaceman-distance they are from post-Modernism’s delirious appetite for the momentary salve of short-term innovation.

These are some of the strangest paintings or painted objects I’ve ever seen. Stuart’s “Doppelbangers” almost text each other! They preen with a new outlandish intimacy. They put you off—with their odd palettes, their shaped-canvas, lozenge-like deviations from the crossed rectitudes of horizontal and vertical—until they take you in again, with a prodigality that is all the more moving for being so unexpected. Stuart’s picture-objects are carefully careless, the lop-eared puppies of painting.

“but a weak smile”, 2012, commercial painter’s linen, weft partially removed; remaining warp spranged, gesso, gold leaf, unique hand built porcelain stanchion hardware. Courtesy the artist.

Others of her works—we still call them paintings—bear incisions, slits, crevasses, crazy pie crust-crimped-and-fluted edges, buildups of paint as thick and ropy as marine cable, surfaces of plaster, slathered with unlooked-for savoir-faire onto linen supports. What else are they but protest paintings that protest their innocence?

I said earlier that I’d get back to “sprang” and “spranging.” Sprang is an ancient Danish weaving procedure, now mostly displaced by the less Nordically muscular act of knitting. It comes into Beth Stuart’s picture-making as a weaving technique that involves the intertwining and twisting of threads or cords over one another in order to form a strong, yet rather draughtsman-like openwork mesh. She used it extensively, as the title suggests, in her “what bonds are these?” exhibition in Montreal last year. Sprang—or spranging—is a clarified, more openly bodily manifestation of weaving—one that exposes the material’s bridgework, you might say. Spranging is sculpting. Or maybe soft architecture. The half-mystical weaving of the Eternal Golden Braid. I don’t know how to do it but I can cite some more poetry—Cole Swensen again (from The Book of a Hundred Hands)—that will convey the sprang aura:

There’s a hand that thinks, that lies inside, that lines the hand that moves and it thinks: “While tying a knot, you can utterly forget, you can think (can be thinking of something else at the time) that muscles have a memory all their own that lives again in a braided time alive I tie….

Beth Stuart’s upcoming exhibition “LOUD.BROWN.SHROUD.” at Erin Stump Projects, Toronto, runs from May 30 to June 30, 2013; her exhibition “WARM.WORN.UNIFORM.” will be at Battat Contemporary in November, 2013 and she is included in “The Painting Project” at UQAM from June 7 to July 6, 2013.

Gary Michael Dault is a critic, poet and painter who lives near Toronto.