“Beshaabiiganan”

Looped footage shot with a go-pro camera submerged into bubbling river water lit the exhibition “Beshaabiiganan,” using the stark space of the Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario (GNO) as a foray into conversations surrounding treaty, nature, community and the future. The artists in this compelling three-person show are Darlene Naponse, Tanya Lukin Linklater and Deanna Nebenionquit. One video was projected across the ceiling; the other, on the far wall. Two tables stood in the middle of the room, a blue stripe painted across the floor and walls.

Tanya Lukin Linklater, Darlene Naponse, Deanna Nebenionquit, Beshaabiiganan, 2017, mixed media, multimedia, installation views, Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario, Sudbury, ON. Images courtesy of Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario.

“Water is our lifeblood,” artist Darlene Naponse told me over the phone. “We wanted the gallery to become immersive, as if you’re under water.” The thick pair of blue parallel stripes the artists painted through the gallery had no start or end point; they flowed through the middle of the floor, up over the gallery doors, around the middle of the walls. They ran over windows and through the gallery office, behind shelving and furniture. As described in the handout accompanying the show, the painted lines were meant to be reminiscent of the Two-Row Wampum Belt, a treaty belt that once had been made as a record of peaceful co-existence between the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Five Nations) and Dutch settlers. The two rows on the belt originally signified the course of two boats, the idea being that the two travel alongside each other but never touch. Artist Tanya Lukin Linklater explained to me, “We [the artists] had been meeting regularly and discussing our individual histories and our histories as Indigenous people. We discussed ideas around the significance of treaty. We wanted to highlight invisible structures such as governance. The show is largely about the structure of the museum or gallery, the space of administration. These invisible structures are real things with real implications. The purpose of the paint-lines encircling the inside of the gallery,” she told me, “was not intended to claim the space at all; it was about a collaboration. GNO reached out to us to put on this exhibition, but there is a long history of museums and galleries not engaging Indigenous projects.” On the subject of treaty and thinking about the exhibition, I was hard pressed not to ask if the show was about Canada’s 150th anniversary. Artist Deanna Nebenionquit told me, “The show was not about Canada’s 150th, but, being 2017, it was a hard subject to avoid.”

In the middle of the gallery stood two identical, tall raw pine tables, each located on either side of the blue parallel stripes making their way through the gallery. They didn’t come across as untouchable art objects by any means, but were identifiable as markers for a place of discussion, negotiation, social interaction—all those things that artist-run centres are known for. “The tables were left quite unfinished and made with local materials,” Lukin Linklater added. “We wanted the tables to also be able to stand in for the boats travelling the river ways side by side.” One thing that all the artists shared with me while talking about the tables was how important meeting with each other became in developing the conceptual outcomes of the show, their visiting each other’s homes and studios, eating together and generally getting to know one another. “We thought that the tables would be a good way to deal with ideas around the domesticity of traditional Anishinaabe women’s work, women as storytellers and fabricators.”

Tanya Lukin Linklater, Darlene Naponse, Deanna Nebenionquit, Beshaabiiganan, 2017, mixed media, multimedia, installation views, Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario, Sudbury, ON. Images courtesy of Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario.

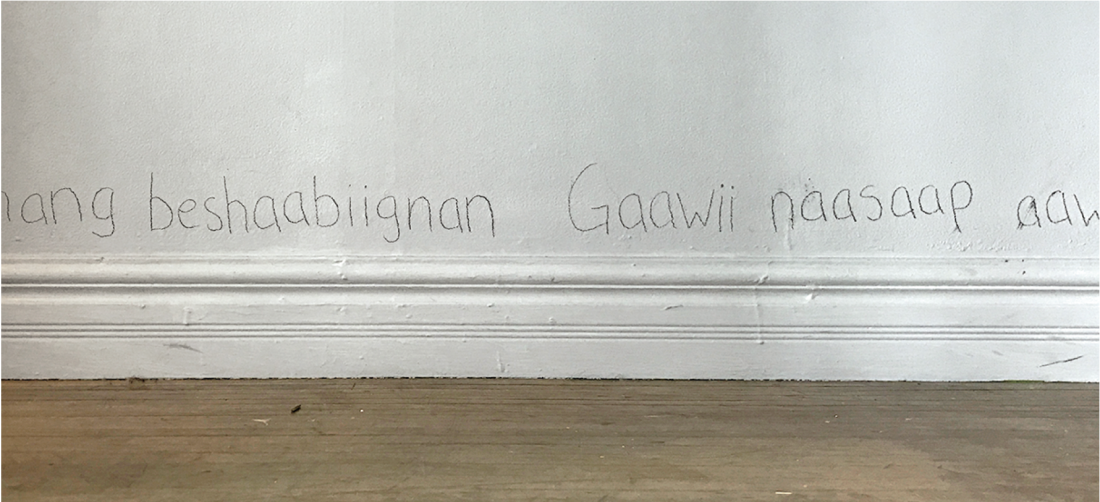

What had to be pointed out to me by gallery staff was an almost hidden text written in pencil around the gallery and alongside the painted blue stripes, a poem collaboratively written in Iroquois by the three artists. The first verse of the poem read:

Maanda beshaabiigan gaawii aawzinoo nendamang beshaabiignan. Gaawii naasaap aawzinoo gaazhiwebak maage waa-ni-zhiwebak.

Maanda dash gaawii gegoo aagnetamsiimigak.

In translation:

This line is not a line in the way that we understand lines to be a history or a progression.

However, this line is not a refusal.

Lines were an active metaphor in the exhibition, given its title “Beshaabiiganan,” the Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) word for “lines.” As on the Wampum Belt, the lines can represent water and rivers, a border, an agreement, the span of time. The lines painted through the show do not flow from point A to point B; they loop, as do the projections. “As in all Indigenous culture there is an endless continuum of history, time is non-linear,” Nebenionquit said, “a forward motion in art, how that relates to our communities, and it always comes back to you as an individual.” Naponse concurs, “In our teachings, everything continues, everything is a circle.”

Naponse and Nebenionquit are both from Atikameksheng Anishnawbek (formerly known as Whitefish Lake First Nation). Lukin Linklater is originally from the Native Villages of Afognak and Port Lions in southern Alaska, and is currently based in North Bay. ❚

“Beshaabiiganan” was exhibited at Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario, Sudbury, ON, from June 1 to July 8, 2017.

Daniel Joyce is an artist and writer based in Toronto.