Bertrand Carrière

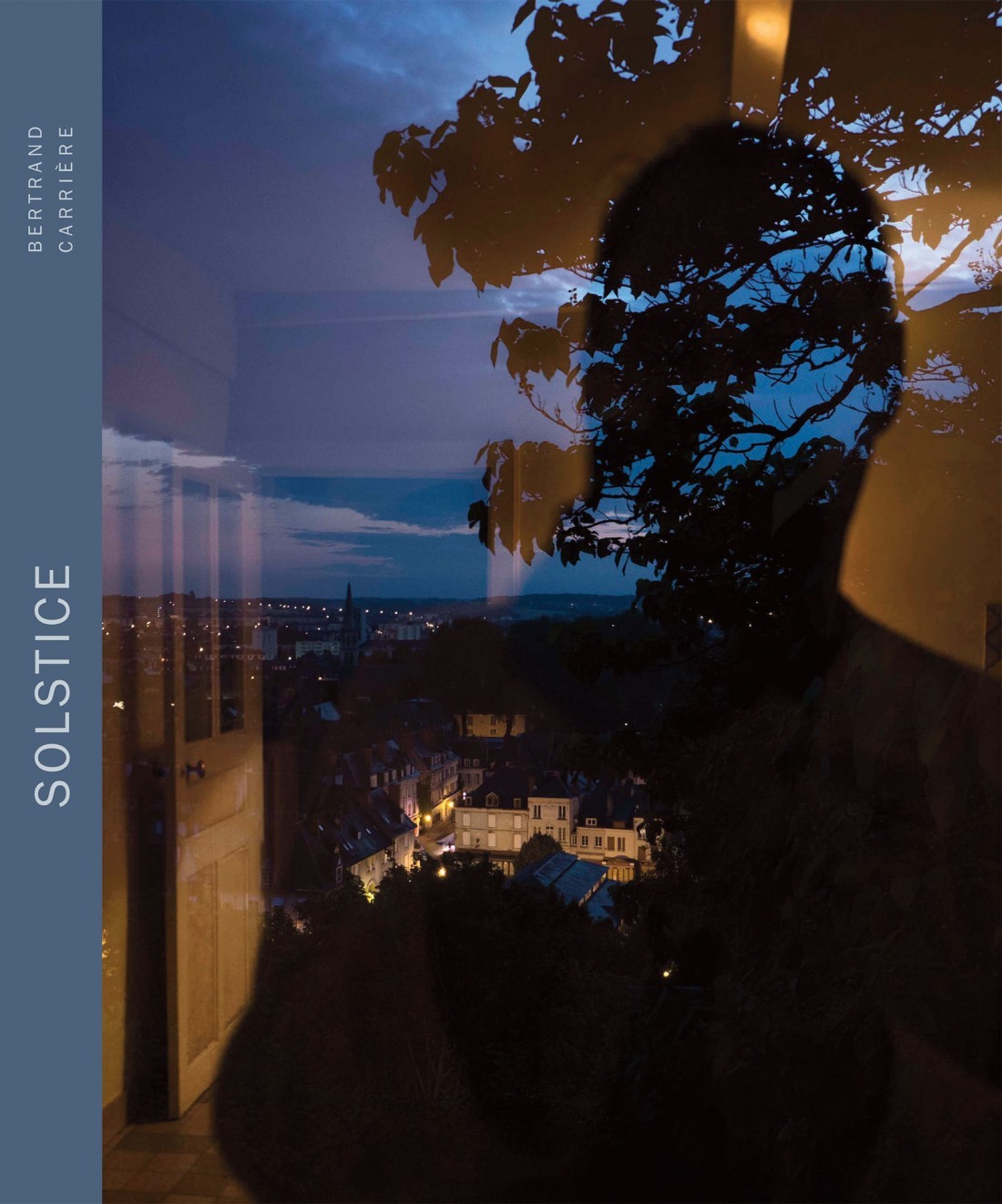

It would be interesting to know what proportion of exhibitions and publications of a retrospective nature are born out of practical, real-life situations, such as an artist’s having to move their studio. It is easy to see how the fact of being suddenly confronted with the mass of past production— in all its concrete, physical glory— would ignite a desire to invest the material with a new sense of order and meaning. This was certainly the starting point of Quebec artist Bertrand Carrière’s recent retrospective projects, a book and an exhibition titled, respectively, Solstice and “Bertrand Carrière. Dans les années … Photographies 1996–2019.” The decision, taken five years ago, to move the contents of his home studio, which included extensive photographic archives, to his country house in the Eastern Townships would trigger for Carrière a process of self-reflection. The first direct outcome of this process was the creation of a personal website, itself an endeavour that promotes a retrospective take on a career. And then came the idea for a book.

Co-published in 2020 by Éditions Plein Sud and the Galerie d’art Antoine-Sirois de l’Université de Sherbrooke, the 301-page publication covers Carrière’s life work thus far, from his first street photographs, taken in the early 1970s, to his latest large-scale documentary series. The aim of the book, which features essays by Mona Hakim, Robert Enright, Pierre Rannou and Carrière himself, is to represent all aspects of the artist’s five-decades-long relationship with photography as an expressive medium. Its abundant illustrations (a total of about 260) are organized in a sequence whose order is not strictly chronological. Instead, distinct series succeed one another in a subtle thematic flow that—much like Carrière’s photographs—creates gentle impressions in the mind of the reader. It is clear from this sequence that considerable attention has been paid to editing, which comes as no surprise, given this photographer’s particular skill at artfully combining large amounts of imagery, whether in the form of books or series. In this case, editing was the result of a close collaboration between Carrière and Hélène Poirier, director of Plein Sud and herself an expert in photographic publishing.

The idea for the exhibition, which was shown at the Galerie d’art Antoine-Sirois from September 8 to October 17, 2020, came after the book and took a distinct approach to Carrière’s oeuvre. Presenting a tight selection of works described by the photographer as his “key works,” all dating from the mid-1990s onward, the exhibition was curated by art historian and long-time collaborator Mona Hakim. The exceptionally high ceilings and openness of the gallery space lent themselves well to the artist’s larger-scale photographs, which were grouped into series and accompanied by extended wall texts. While providing only a glimpse—relatively speaking—into Carrière’s total creative output, the exhibition had the tone of a retrospective, with each of the 50 or so images selected acting as stand-ins for larger bodies of work. The 12 images chosen to represent his ongoing series “Le Capteur,” 2006–, for example, constituted only an infinitesimal sliver of a daily, autobiographical practice that has been generating hundreds of thousands of photographs over the past 15 years. What the exhibition revealed perhaps most clearly, for me, is the monumental character of Carrière’s work—the fact that whether he is documenting war ruins in Dieppe or capturing ephemeral fragments of his everyday life, he seems to consistently conceive of his projects as colossal monuments to the past.

The exhibition and the book both posit the idea that his practice can be divided—as I have just done—into two major strains: the conceptual documentary projects that actively engage with collective memory and history, such as “Lieux mêmes,” 2006–2009, and “Miroirs acoustiques,” 2019; and the series that bear witness to his personal history, such as “Voyage à domicile,” 1985–2000, “Signes de jour,” 1995–2001, and “Le Capteur,” 2006–. A third, though perhaps less fundamental facet, is Carrière’s exploration of the medium of cinema, which has found expression in series such as “Les image-temps,” 1997–2000, and “Les images noires,” 2018. In the book, the first two streams are discussed individually in Enright’s and Hakim’s respective essays. It is tempting to keep up this theoretical separation, yet both authors make insightful statements about Carrière that, when taken together, provide a novel perspective on his practice. Enright, in his investigation of the artist’s role in making collective memory, describes him more as an instigator of photographic situations—of photography-as-ritual— than as a removed taker of images. In Carrière’s documentary projects, photography is tantamount to a performance during which the photographer is fully immersed in the act of memorializing. Hakim, who characterizes the autobiographical series as mapping out a “geography of the intimate,” compares Carrière’s creative process to a form of impulsive— even compulsive—automatic writing in which a private visual lexicon is rehearsed. In other words, both emphasize the idea that, in his hands, photography is an art that is performed, deliberately yet intuitively, in the present moment.

The book’s opening essay, signed by Carrière himself, was included to provide an account of his earliest work, from his first taking up the camera as a teenager until the end of the 1980s. Although short, the text adds a valuable injection of social history into the mix, manifested in vivid descriptions of Montreal’s photography scene in the 1970s and his early experiences as a freelance photojournalist. The book, unlike the exhibition, includes a significant number of images that relate to this chapter of his career, which, though perhaps less monumental, is nonetheless rich in experimentation and instinctual responses to the world. What these images demonstrate, in my view, is that Carrière’s photographic process has always been deeply intuitive and immersed in the present. Over time, this once unconscious process has become his signature. ❚

“Bertrand Carrière. Dans les années … Photographies 1996–2019” was exhibited at the Galerie d’art Antoine- Sirois de l’Université de Sherbrooke from September 8 to October 17, 2020.

Zoë Tousignant is a photography historian and curator based in Montreal.