Bertram Brooker

I have a longstanding, fragrantly nostalgic relationship with the art of Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) and it is based on a painting of his that I once loved, wanted, but was too unadventurous to buy. It was a large horizontal landscape—large for Brooker—painted in 1939 at the Sandbanks Provincial Park near Picton, Ontario, where I had often been taken as a child. I saw it at the Jerrold Morris Gallery on Prince Arthur Street in Toronto, sometime in the mid-1970s. Jerry was asking $900 for it. It wasn’t much really, but it was more than I had.

I was hoping I might see the picture again in the exhibition Phillip Gevik has so painstakingly assembled over the past few years, hosted recently at his gallery in Toronto, but it wasn’t there. I described the painting to Phillip and casually asked him what it might be worth today. “Oh,” he told me airily, “maybe $85,000–$90,000.” And all I’d had to do was go to my bank manager and tell him I wanted to build a carport or something, and I know he would have cheerfully lent me the money. Failure of nerve has a lot to answer for. But even without my Sandbanks painting, Gevik’s exhibition, “Bertram Brooker: A Creative Force” was a pleasure to explore.

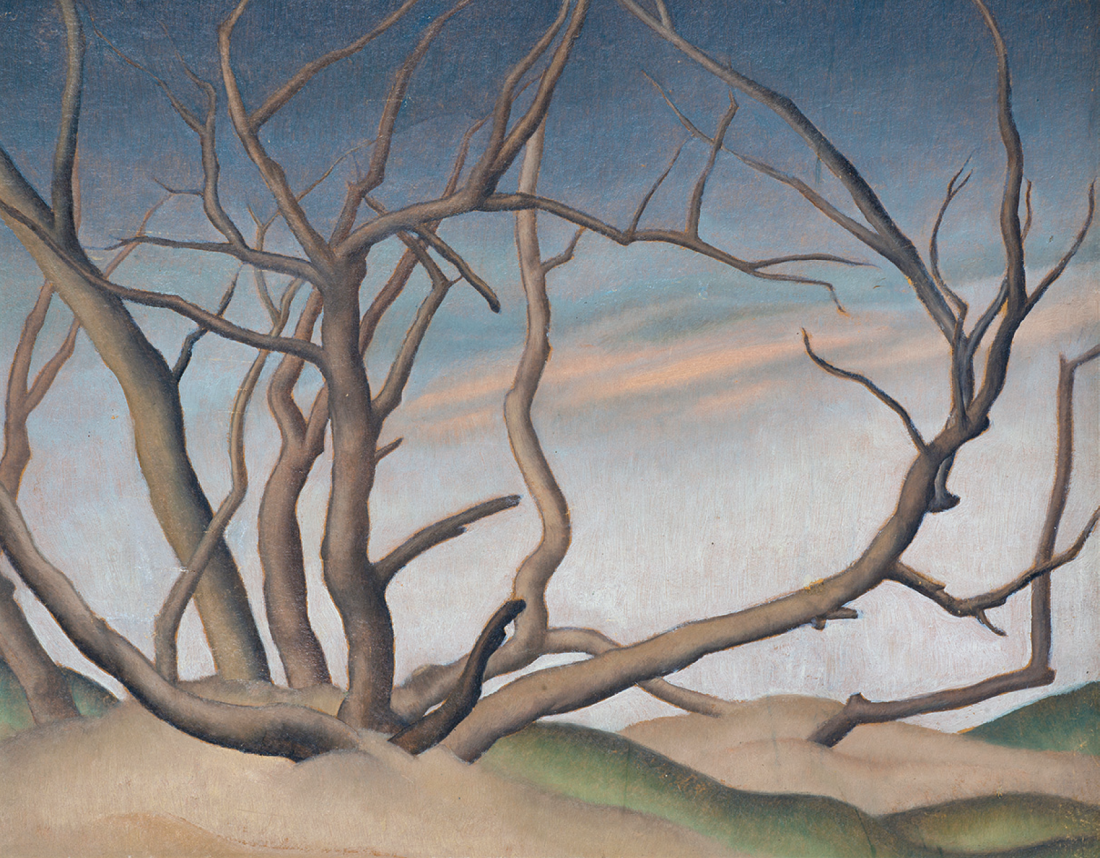

Brooker was a protean character—a very successful advertising executive, a writer of books about advertising, a novelist (his 1936 novel, Think of the Earth, won the first Governor-General’s Award for fiction), and a poet. His reputation today is as a painter. A painter who, obeying the promptings of his restless intelligence, worked in remarkably diverse styles, ranging from the Van Gogh-like earnestness of his scruffy pair of women’s brown shoes (Shoes, 1934–35), through clarified LeMoine FitzGerald-like landscapes and tree studies (Manitoba Willows, c.1928) for example, and on to enthusiastic forays into experiments in early-modernist abstraction—the paintings upon which his reputation now seems mostly to be based.

Bertram Brooker, Double Bass, c.1953–1954, oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches. Courtesy: © Walter Willems and Gallery Gevik, Toronto.

These abstractions blow hot and cold—and have aged rather badly, for the most part. Like the late, non-representational paintings of Lawren Harris—but without the supercharger of theosophy to help power them—the abstracted works Brooker made in the 1920s and early ’30s trade formally in the knee-jerk Modernism so often represented, at this point in cultural time, by an obvious, easy kind of art-deco streamlining. Metaphysically, they wallow in a mawkishness that pushes the pictures even beyond sentimentality into some queasy state of mystical banality (Crucifixion, 1927–28, The Finite Wrestling with the Infinite, 1925, or his Striving from 1930), which—if you don’t count its pleasant soft, powdery colour—seems to owe a great deal, structurally speaking, to a rather serious misreading of Boccioni’s seminal sculpture, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space from 1913. But there is one thing about Brooker: he gets better as he goes along. Which is not something you see very often.

In 1937, he painted a perfectly enjoyable still life called Green Bottle—which is deftly composed and demonstrates a nice feeling for the achieving of transparency (in glass) and reflection (on a bottle). Ten years after that, in the late 1940s early 1950s, he moves, with what looks like confidence, into the making of mostly non-representational paintings that demonstrate real grit and a salutary deliberateness. These works lift him decisively out of the easy, mellifluous proscriptions of the modernist look, which is, after all, a stylism.

You see it, for example, in a watercolour like Abstract No. 3 (Vertical Progression) from 1948, with its close-packed aggregation of sand-coloured shapes (some look a little like books, one seems to be a vestigial violin). The picture is, admittedly, pretty late for early Cubism, but there is a sinewy musculature there as well that lends the work strength and integrity.

Manitoba Willows, c.1928, oil on board, 12 x 15 inches. Courtesy: © Walter Willems and Gallery Gevik.

Similarly with Abundance, an oil painting from the same year, 1948. Here, the chunky, earth-coloured objects of Abstract No. 3—cones, flanges, slabs—are lent a botanical energy that blossoms out into another painted gathering, made up this time, however, of highly abstracted flower, leaf and shell shapes, with hints of pale berries and calligraphic tendrils of stem and vine. The odd, restrained palette Brooker employs for the painting (whites, creams, greys, beiges, browns, dusty, remote pinks) lifts it quite effectively beyond any appearance of easy, horticultural exuberance, beyond the mystical glorification of the natural world, which seems to have come so easily to Brooker in the previous two decades, and replaces all that with a moody, almost tough-minded gravitas.

Two other paintings of Brooker’s in the Gallery Gevik exhibition are interestingly poised between what seems like the newly achieved high seriousness of his Abstract No. 3 and Abundance and a worrisome retreat from that plateau of achievement. The pictures, you feel, could go either way. The first of the two is Autumn Bouquet, 1948–50—where the leaves and berries of Abundance have been ordered into a grid in shallow cubist space, and are now clamouring, as a result, to be seen as merely decorative.

The other, however, is more forceful—a watercolour titled Recessional from 1951. Happily, it falls vigorously forward, where Autumn Bouquet tumbles backwards into the mannerisms that sometimes seem to block Brooker’s progress.

Given the picture’s vaguely treble clef shape, I assume the title Recessional is being used here in the church-music sense of “withdrawal” (as at the end of a church service or a wedding), rather than in the wider sense of painful memory or poignant recollection (as in Rudyard Kipling’s plangent military poem, “Recessional”).

But music analogies or not, the painting, which is built on a big serpentine “S” shape, shot through with a couple of armature-like diagonals, is so exquisitely, so delicately painted (in yellow greens and olive greens and, briefly, at the top and bottom, conch-shell pinks), it draws away from the lurking sentimentality of that easiest of all analogies—the painterly and the musical—to come to rest as a finely interwoven and interlocked figure, pulled together into itself like a tightened knot. ❚

_“Bertram Brooker: A Creative Force” was exhibited at Gallery Gevik, Toronto, from May 3 to May 31, 2014. _

Gary Michael Dault is a critic, poet and painter who lives near Toronto.