Beautiful Parasites

In “simplest of gestures,” Tammy Salzl’s recent series of powerful watercolours, you can’t take your eyes off the flesh. The Montreal-based artist has shifted from her trademark oil paintings of figures in elaborate landscapes to rendering figures on simplified backgrounds. “The oils were operatic, crazy, frantic and in-your face,” she says, whereas the watercolours are composed of “hundreds and hundreds of very soft, light and washy glazes.” She wanted to see if in the figure alone, there was a way to condense the narrative energy and psychological complications offered by the figure-in-landscape works. “By taking the figure out of the landscape and putting the landscape into the figure, I went from allegory to metaphor. I see it as a metaphorical site where I can stage and explore the human condition.”

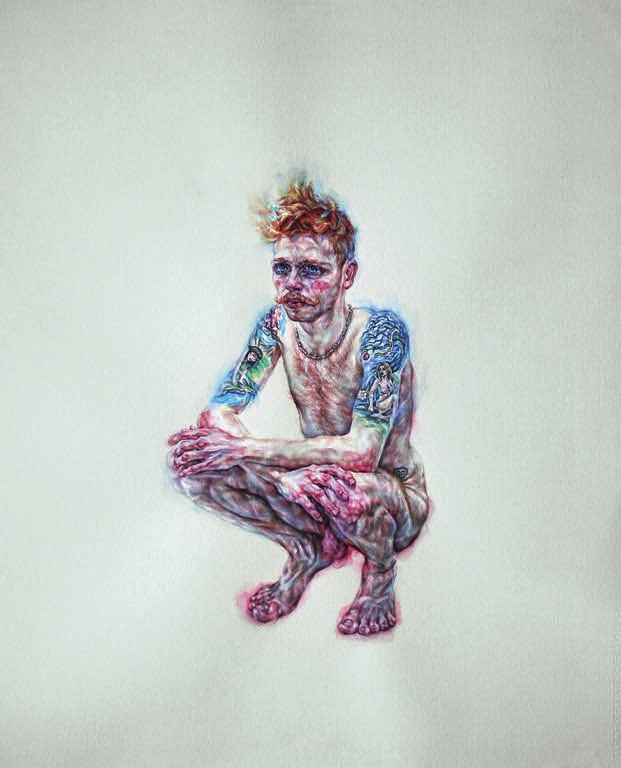

Fights Like A Girl, 2013, watercolour on paper, 16 x 12 inches.

The condition she is exploring is a wide one, from the delicate look of adolescent sexuality and gender identity (Juvenesence and Girl Inbetween) to the heroic fragility of a friend who overcame a life-threatening addiction (Thunderheart) and to the iconic theatricality of Evergon (Fights Like a Girl). In all the portraits, her painted skin has retained its particular quality, a combined “churning, pulsating, slightly grotesque and yet visually beautiful surface.” Her intention is to make it at once vulnerable and confrontational. In her figures, she picks certain parts of the body to exaggerate—hands, feet, knees and elbows—any place where the body angles or isolates itself in space. She renders these places “as if they were isolated wounds, indicators of human suffering and our own mortality.”

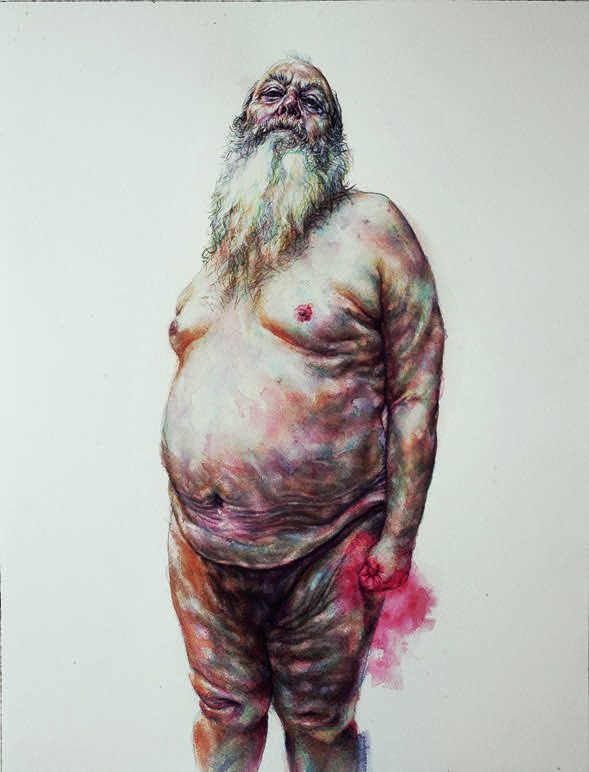

Nokken, 2013, watercolour on paper, 25 x 21 inches.

They also register her deep compassion. Girl Inbetween is a portrait of her 15-year-old daughter, Ronan. “I wanted to capture her bravery and to record the fine balance between her psychological and her physical self, so I asked her to put on the dress she wore when she first decided she was going to live fully female.” The dress is too small and the look on her face is sweet and good humoured. Most often, Salzl’s figures look out of the picture without apology. It is her sense that the direct gaze makes the viewer complicit with whatever or whomever they are looking at. In a world of simple human gestures, complicity is acceptance.

Girl Inbetween, 2014, watercolour on paper, 24 x 19 inches. All images courtesy the artist.

Salzl is aware that her watercolours often elicit severe accusations of indulging in the brutal and the grotesque. It is a reaction she anticipates for its utility. Her intention is to repulse the viewer with the grotesque and then mediate that alienation through beauty. She wants to shift the story you thought you were being told at the beginning. “I want to create a visceral and emotional response that will evolve in the brain,” she says. “I like to think of my paintings and drawings as beautiful parasites. You come to them through feeling and over time they unfold in the mind.” ❚