“Bastards of Misrepresentation: Doing Time on Filipino Time”

Of all the art centres in Asia, Manila has one of the richest, most singular histories, but its contemporary scene is only recently garnering broad attention. Contemporary Asian art collectors have been among the first to catch on to the teeming vibrancy of the city’s art sector, whose diversity resists easy categorization. One of its champions is the recently returned Manuel Ocampo, celebrated for the past two decades in the West, now based in Manila and deeply involved in the emerging art scene. But emerging is probably not the correct term. Painting, for example, draws from a history of colonization going back to the Spanish, Portuguese, Americans and even Japanese, yet its hybrid morphology is uniquely its own. An example of Manila’s fecund, diverse, potent and highly informed contemporary art was on view recently in Berlin. “Bastards Of Misrepresentation: Doing Time On Filipino Time” was curated by Manuel Ocampo for the Freies Museum in fall 2010. Ocampo says this show is about the cultural scene in the Philippines but is not a definitive show about Filipino art. It draws from the culture’s identity as a hybrid and, oddly, from the pervasive misrepresentation of its people. It is about authenticity or, to be more accurate, the alternate conditions of authenticity.

The first room in this ambitious exhibition holds Pow Martinez’s assemblage of painted boxes housing his looping cityscape sound piece. Also in this gallery are photos and a painted installation, complete with a basketball hoop and balls by David Griggs. The viewer immediately enters the art scene of Manila through its underworld, via the looped street cacophony emanating from Martinez’s speakers hidden among the trashed and painted boxes strewn near the entrance, and the photographs by Griggs, with the tattooed figures of a local Manila gang, the Bahala Na Gang. Griggs, an Australian artist now based in Manila, has delved into the megalopolis underworld and become a respected local member of the art scene. It was Pow Martinez’s intention to link the streets of Manila and Berlin—the cacaphonic sound installation combining elements of the Berlin riots with those of the People Power Revolution in the ’80s.

Bea Camacho, Efface, 2008, single-channel video, 11 hours. Photograph: Poklong Anading.

The exhibition continues on two more floors with what, on first reading, appears mostly an odd grouping of graffiti-heavy paintings, photos, sculpture and video. If you flip through the impressive 140-page catalogue, you’ll see this is no random grouping at all. Most of these artists have international exhibition records. Bea Camacho, an award-winning Harvard graduate who currently splits her time between Boston and Manila, presents a video where she is carefully crocheting herself into a cocoon in the carpet. The writer and curator Carina Evangelista identifies it as “a reversal of the clichéd metamorphosis,” and many have linked such work by Camacho to the Diaspora experienced by many Filipinos. When pressed about this interpretation, Bea told me that the piece is about erasure and absence, and where it is not directly about the Filipino Diaspora, it is still an experience she understands having grown up in many places and away from family. Interpretations of transience are applicable since the piece is also about isolation and creating one’s own environment while appearing quietly to withdraw into the architecture, wavering meditatively between a state of separation and belonging.

Kevin Power’s essay, “The World We Live In,” seems to wrestle with whether or not to associate Ocampo’s curated exhibition with Nicolas Bourriaud’s recent writings on a concept of contemporary art he calls “altermodern.” I found a blogger flippantly referring to the “altermodern” as “postmodernism with a passport.” It deals with cultural translation, time-space crossings, mental nomadism and the experience of wandering. It’s therefore probably a good perspective for a show such as this, especially relevant to the previously noted video performance by Bea Camacho.

“We have to get out of this dialectical loop between the global and the local,” Bourriaud wrote, to “get rid of the binary opposition between globalization and traditions.” An artist ready to tread in such waters is Maria Cruz, who presents a painted construction derived from the Sari-Sari store, a common, small variety store in the Phlippines that also references the German “imbiss” or fast-food stands found throughout Berlin. Crossover culture is not a strange application for contemporary Filipino art. Kevin Power calls the meeting place between the global and the local the “glocal,” and Cruz shows that these are not just locations of commerce but, indeed, meeting places. She has created an installation borrowing the Tagalog term “sari sari,” meaning “variety,” while simultaneously riffing on the Bauhaus principle of form following function. It therefore doesn’t seem strange to consider the show from Bourriaud’s altermodern perspective, which synthesizes Modernism and post-colonialism. Nicolas Bourriaud calls this “creolisation.” Manuel Ocampo might prefer it referred to as “cultural hybridization.”

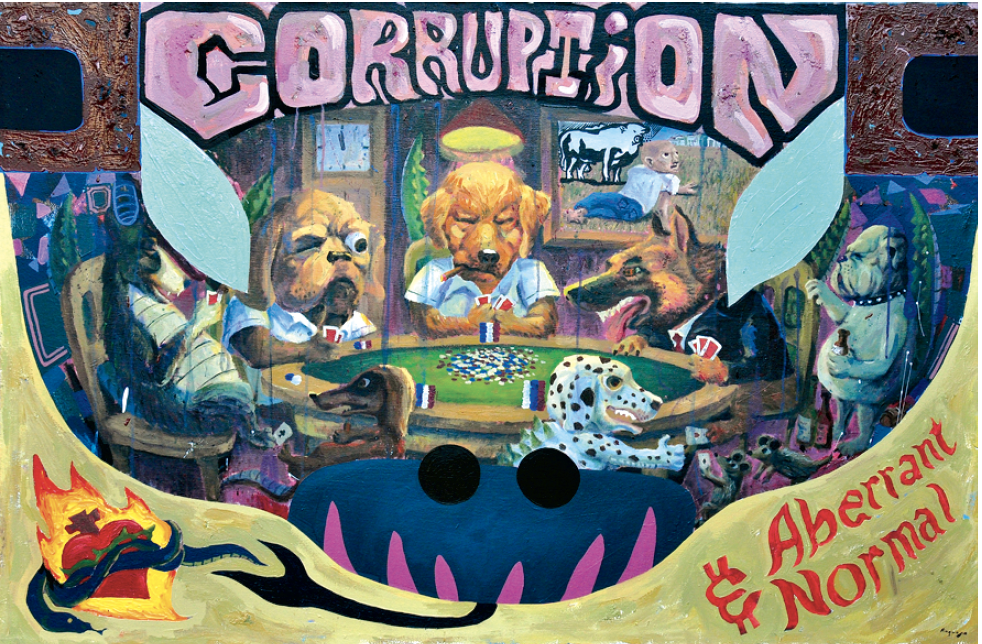

Jucar Raquepo, Corruption, 2009, acrylic, oil and textural mediums on canvas, 40 x 60”.

Carina Evangelista accurately observes that an initial reading of the paintings of Jucar Raquepo might leave a viewer with the impression that they “Ain’t nuthin’ but kitsch,” being a jumble of garish colours, iconography and low Pop imagery, notable among them, dogs playing poker. But someone familiar with the streets of Manila will soon realize that much of the imagery is an appropriation of Jeepney decals and designs; even Raquepo’s colour palette is a clue. The mint greens, lilac, brown and peach are government-issued colours, used by the Department of Transportation to cover up anti-government slogans. It may seem an unlikely clue, but in case you missed the significance of the colours, the large, pink word “Corruption” is painted across the top of the canvas. In fact, more than just a jumbled exercise in lowly kitsch appropriation, the paintings question the ideals pressed upon the masses. About the paintings of Raquepo, Kevin Power writes, “It is the Jeepney aesthetic mixed with the baroque ornamental indulgences of the Filipino Catholic Church. His commentaries are aimed, as with a number of these artists, at the legacies and contortions of contemporary art, at the miseries of political ambition and at the blatant stupidities of consumer living.” Raquepo, it becomes apparent, is not an uninformed outsider artist. Far from it, he appears an ideal candidate to elevate the practice of appropriation to Bourriaud’s more favoured term of “formal collectivism.”

The varied and dioristic range of art practices and strategies is more than hinted at with the range of artists shown in the group exhibition at The Freies Museum. There are the videos of Poklong Anading, the sculptural fusing of ethnographic symbolism with technology in the work of Gaston Damag, and the raw, vulgar and, yet, multifaceted and enigmatic figurative paintings of Robert Langenegger. A mere few feet away, Ocampo isn’t afraid to go in the other direction with the paintings of Jayson Oliveria and Argie Bandoy that reach into the rich history of painting. Kevin Power writes that Bandoy’s paintings “ironize the Modernist tradition that has been imposed upon them as a dominant referent.” He borrows from other artists like Schnabel, Richter or possibly even Ocampo, painting as much with the language of painting as with pigment, and not afraid to show ironic references with a slight nod to Polke and Baselitz.

Installation view of “Bastards of Misrepresentation: Doing Time on Filipino Time” at the Freies Museum in Berlin, 2010. Background (left to right): David Griggs, Donkey Root, 2007, acrylic on canvas; Argie Bandoy, Salvo, 2008, oil, encaustic, spray paint and enamel on canvas, 145 x 154 cm; Pow Martinez, Shit and Piss Factory #2, 2010, acrylic on canvas, 19 x 17’. Foreground: Pow Martinez, Shit and Piss Factory #1, 2010, mixed media with sound installation. Photograph: mm yu.

M M Yu and Lena Cobangbang both draw upon the detritus of the city. Yu documents it while Cobangbang reconstructs it into her own virtual worlds suspended in edible materials. Diversity is also shown with the seeming gulf between two of the more senior artists, Gerardo Tan, whose conceptual ideas pass between the nature of painting and photography, and Romeo Lee, self-described as “part-time artist, full-time rocker and lover,” whose energetic wall mural in The Freies Museum walks that line between the world of underground music in Manila and the punk scene of Berlin.

When ascribing a stamp or identity to a “scene,” we look first for the commonalities. One of the Ocampo’s main intentions with this show was to “provide opportunities for the artists involved by illustrating the diversity of practices currently being explored by the Filipino avante-garde.” Closer scrutiny will also reveal artists unafraid to show art that works on multiple levels with a sophistication that may be a surprise if the viewer is looking for only the exotic and raw. Kevin Power reminds us that these Filipino artists, although flippant, impertinent and linked to a global underground, are well informed. No haphazard outsider grouping, it is indeed a rich and intelligent result of wise curation by Manuel Ocampo. “I grew up being taught to doubt the word ‘authentic’ or ‘authenticity’,” Ocampo tells me. His aim with this exhibition in Berlin is to challenge the notion of authenticity within constructed notions of identity and outside a social construct based on consensus. Additionally, I believe the sophistication revealed comes from questioning the very certainties we may hold about our ideas of place. This could come from adopting a reading of global art that remembers, as Canadian theorist Northrop Frye would remind us, that the centre is where you are. ❚

“Bastards of Misrepresentation: Doing Time on Filipino Time,” curated by Manuel Ocampo, was exhibited at the Freies Museum in Berlin from October 22 to 28, 2010.

Matthew Carver has shown his work in venues such as the 12th Cairo Biennale and in solo presentations in Europe, Asia and North America. He lives in Berlin.