Automatisme Beyond Borders

Thérèse Renaud, Françoise Sullivan, Rita Letendre

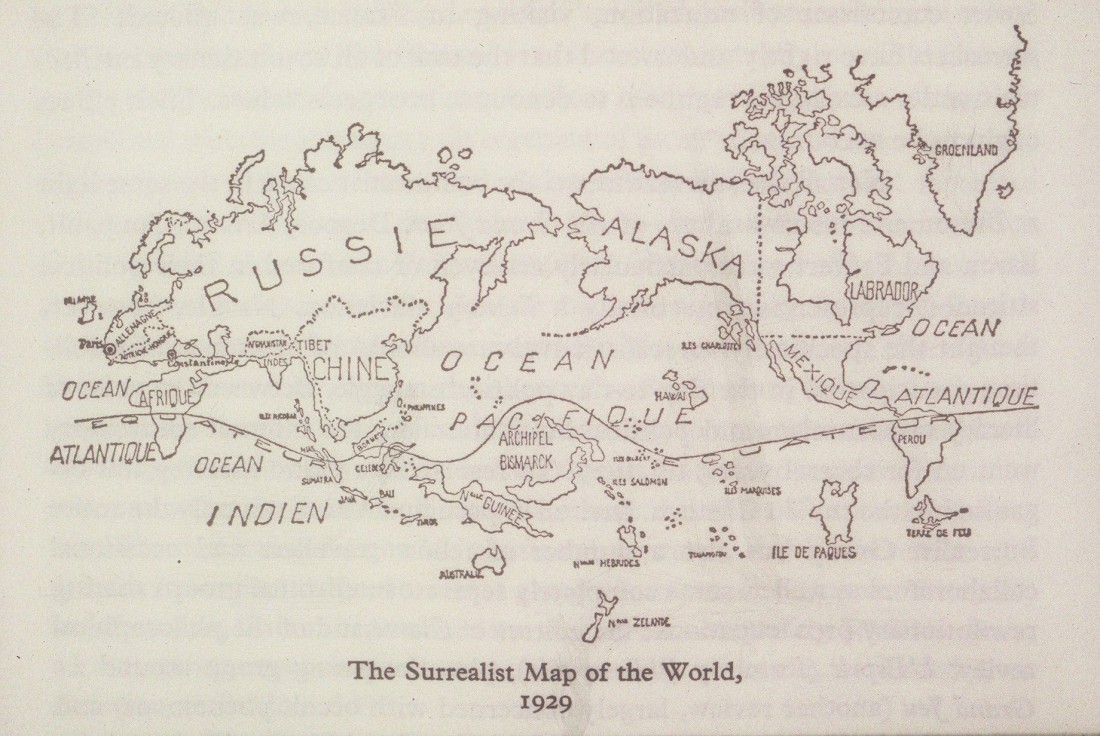

The Surrealist Map of the World, 1929, originally published in the magazine Variétés.

Surrealism is back on the contemporary art map thanks to a recent slate of high-profile exhibitions. As a collective creative action linking collaborators across borders, surrealism embodies a powerful alternative to the widespread reassertion of national borders. But if the surrealists still have much to teach us, these exhibitions argue that their lessons will require a revised chronology and expanded geography of global modernisms. Where do the contributions of Canadian artists fit into this new world picture? Taking its title from The Milk of Dreams, a visionary children’s book by the British-born Mexican surrealist Leonora Carrington, the 59th Venice Biennale orchestrated a fruitful dialogue between historic and contemporary art practices with an accent on the contributions of women surrealists. In parallel with the Cecilia Alemani-curated Biennial, Venice was also host to “Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity,” an exhibition jointly organized by the Peggy Guggenheim Collection and the Museum Barberini that explored the movement’s debts to alchemy and the occult. “Surrealism Beyond Borders,” which travelled to the Tate Modern following an initial presentation by the Metropolitan Museum, concurrently mounted a bold decentring of established histories of the international movement. Though its founding is usually dated to the French poet André Breton’s publication of the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, the decolonial counter-narrative proposed by curators Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale set out “to challenge the equation of Surrealism with Paris” by unearthing global manifestations of the surrealist tendency, from Aleppo to Martinique.

D’Alessandro and Gale’s planetary vision of surrealism draws inspiration from, but also critically revises, the imaginative geography of an iconic map originally published in a 1929 issue of the Belgian magazine Variétés. The World in the Time of the Surrealists visualizes the avant-garde movement’s anti-colonial agenda by enlarging non-Western locations such as Easter Island and Vanuatu while pointedly diminishing the relative size of colonial powers such as France and the UK. Canada receives mixed treatment at the hands of the unidentified surrealist map-maker. Its populous southern latitudes—home to the colonial metropoles of Toronto and Montreal—are drastically compressed, while its Arctic and Subarctic regions gain outsized visibility. Despite the overall prominence of Canada on the surrealist’s revisionist map, the contributions of Canadians to the surrealist venture remain peripheral in recent reassessments of the international movement.

Rita Letendre and Françoise Sullivan, 2019. Courtesy Gallery Gevik, Toronto.

While contemporary Canadian artists are admittedly well represented in Alemani’s Biennale, the surrealist-inspired Automatistes who ignited a cultural revolution in mid-century Quebec receive only passing mention in the catalogue of “Surrealism Beyond Borders.” Françoise Sullivan’s iconic plein-air performance Danse dans la neige, 1948, is similarly the sole Canadian inclusion in the pivotal Met-Tate survey. Such omissions cannot be corrected through a simple rehashing of established accounts of surrealist “influence” on the network of artists affiliated with Paul-Émile Borduas, the Montreal-based painter, anti-clerical activist and leader of the Automatistes. What’s needed instead is a radical rethinking of those narratives, one that takes its cue from the decolonial and feminist valence of D’Alessandro and Gale’s upending of Paris-centric chronologies of surrealism in favour of a non-linear and nonhierarchical remapping of the affinities linking diverse flowerings of surrealism and surrealist-aligned projects across places and times. We are just as much in need of a new map of Automatisme, one that would challenge its familiar equation with Montreal by bringing to the fore transnational synergies and solidarities. Building on the work of feminist historians Rose Marie Arbour and Patricia Smart, I will propose such an alternative geography, with a focus on the contributions of three women Automatistes: the writer and performer Thérèse Renaud, the multidisciplinary artist Françoise Sullivan and the painter Rita Letendre.

Françoise Sullivan, Danse dans la neige, 1948, photographs of Françoise Sullivan during performance, 38.7 × 38.7 centimetres. Photo: Maurice Perron. Private collection © Françoise Sullivan/COVA-DAAV (2023).

Françoise Sullivan, Danse dans la neige, 1948, photographs of Françoise Sullivan during performance, 38.7 × 38.7 centimetres. Photo: Maurice Perron. Private collection © Françoise Sullivan/COVA-DAAV (2023).

In her groundbreaking reassessment of the marginalized contributions of women artists to Automatisme, Arbour persuasively argued that the writings of a teenaged Thérèse Renaud beat Borduas to the punch in articulating the theoretical bases of the movement. Three calendar years in advance of the latter’s lead text for Refus global, the 1948 Automatiste manifesto whose vision of social change lit the long fuse of the Quiet Revolution, Renaud began publishing poetry in the pages of the influential Université de Montréal student newspaper Quartier Latin. Where Borduas’s lead text in Refus global delivers rhetoric, Renaud’s poetry shows us surrealism in action.

Inspired by Freud’s use of free association to probe the workings of the unconscious, André Breton defined surrealism as “pure psychic automatism.” The French poet thus equated the international movement with the literary technique of automatic writing from which the Quebec-based Automatiste group would later derive its name. Breton influentially described automatism as the “dictation of thought, in the absence of all control exercised by reason, beyond all aesthetic or moral preoccupation.” A poem published in the November 13, 1945, issue of Quartier Latin by a then 18-year-old Renaud performs precisely such an unfiltered registration of “the real functioning of thought.” A vivid collage of oyster shells, caterpillars and the author’s own body parts, Renaud’s untitled poem is set in motion by nocturnal travels. Breton’s L’Amour fou had demonstrated that such striking juxtapositions of imagery are the chief product of automatic writing. Hence visual artists’ interest in a literary procedure that anticipated present-day AI image generators like DALL·E. As Borduas clarified in a letter to fellow Automatiste—and Renaud’s future spouse—Fernand Leduc, “We have only extended to painting the freedom [that the surrealists] have brought to literature.”

The strongly visual character of Renaud’s poem is amplified by an accompanying artwork by a then 18-year-old Jean-Paul Mousseau. In keeping with Breton’s automatist principles of spontaneous juxtaposition, Mousseau’s near-abstract drawing does not simply “illustrate” the text. Rather, it functions in an exponential relationship to Renaud’s textual fever dream. This multidisciplinary application of surrealist strategies by the enfants terrible of the nascent Automatiste circle cleared a path for the two artists’ collaboration on a subsequent book, Les sables du rêve. Hailed as the first surrealist text published in Canada, the 1946 book by Renaud and Mousseau exemplifies the collaborative methodologies championed by surrealism. Indeed, it shows Renaud to be more “surrealist” than Borduas, who was perpetually wary of being claimed by the paternalistic Breton.

Renaud later recalled that the process of selecting poems for inclusion in this hallucinatory volume followed the same dictates of unpremeditated assemblage as the procedures of automatic writing employed to write them. Despite the book’s titular nod to the elder statesman of surrealism (a reference to a recent Breton publication), the more immediate model for Renaud’s text was not in fact Breton but fellow surrealist prodigy Gisèle Prassinos. A copy of the Turkish-born Prassinos’s collection of poems La sauterelle arthritique had been gifted to Renaud by her sister Louise, a painter who was then employed as a governess for the children of the New York art dealer Pierre Matisse (the son of painter Henri Matisse). Rose Marie Arbour has painstakingly documented Louise Renaud’s importance to the Montreal avant-garde in establishing contact with European surrealists-in-exile living in the United States and in establishing a New York pied-à-terre for visiting Automatistes.

Prassinos has too often been written about, and tacitly written off, as the archetypal femme-enfant, or woman-child, of male surrealist erotic fantasy. Astonishingly, she originally published some of the poetry later collected in La sauterelle arthritique as young as 15, following her discovery by Breton’s circle. “Gisèle Prassinos’s tone is unique, all the poets are jealous of it,” Breton effused in his Anthology of Black Humor, 1940. But it is important to underscore that, as literary scholar Bonnie Ruberg has documented, Prassinos would later distance herself from the model of automatic writing that was applied by Breton and other surrealists to interpret her absurdist tales. Ruberg instead reads Prassinos’s monstrous bodies, which fuse elements of human and animal anatomy with everyday objects, as critiquing idealized images of “woman.” Ruberg’s interpretation resonates with Thérèse Renaud’s meditations on the collage-like figures that inhabit her own poems in Les sables du rêve. These, she wrote, expressed her “inner turmoil when I found myself misunderstood and troubled in a bourgeois family atmosphere, being educated by nuns.” With eyes in their nostrils and phallic snakes worn as ties, Renaud’s mutant bodies also anticipate Cecilia Alemani’s curatorial interest in the “alliances between species, and worlds inhabited by porous, hybrid, manifold beings” visualized by the canvases of surrealists like Leonora Carrington. Today, Alemani argues, this hybridity illuminates redefinitions of the self in the wake of a deepening climate crisis.

Françoise Sullivan, Dualité, 1947, 1992 re-enactment performed by Annik Hamel and Sophie Corriveau. Photo: Robert Etcheverry. Françoise Sullivan’s personal papers. © Françoise Sullivan/ Dance collection danse (2023).

Françoise Sullivan, À tout prendre, 1980, performed by Monique Giard and Daniel Soulières. Photo: Robert Etcheverry. Françoise Sullivan’s personal papers. © Françoise Sullivan.

Shortly after the publication of Les sables du rêve, Renaud relocated to Paris, where she went on to co-organize an important exhibition of Automatisme with collaborators Fernand Leduc and Jean-Paul Riopelle at Galerie du Luxembourg in 1947. Another artist working collaboratively to promote the accomplishments of the Québécois “gang” beyond Canada’s borders at this time was Françoise Sullivan. Indeed, as art historian Roald Nasgaard has documented, the Automatistes’ first exhibition took place in January 1946 at the Boas School of Dance in New York City, where Sullivan was studying modern dance. Titled “The Borduas Group,” it included works by Borduas and a selection of his young followers— Pierre Gauvreau, Leduc, Mousseau, Riopelle and Guy Viau. Sullivan’s hanging of “The Borduas Group” notably predated the first “official” exhibition of the Automatistes, held in Montreal in April 1946 in an office on Amherst Street (present-day Rue Atateken). Sullivan scholar Allana Lindgren makes a convincing case that Sullivan’s decentring of the Borduas-sanctioned narrative of Automatisme was no mere detour. Automatisme “was not the only influence on her development as a modern dancer and choreographer,” Lindgren insists. Immersing herself in the pedagogy of Franziska Boas, the visionary founder of the eponymous dance school, Sullivan absorbed global influences that challenged Montreal-centric genealogies of Automatisme.

A decade prior to the coalescence of the civil rights movement, the democratically administered Boas Dance Group was firmly dedicated to an anti-racist program of racial integration. Among the African American students whom Franziska Boas welcomed into her studio was Katherine Dunham, who would go on to found her own school and publish a groundbreaking study of Haitian dance. Franziska Boas’s commitment to dismantling systemic racism drew inspiration from her father, the noted anthropologist Franz Boas. The dancer put her principles into action by increasing opportunities for the members of marginalized communities to access educational opportunities, by programming non-Western performance styles and by hosting innovative anthropological seminars—including a 1941 lecture by Boas père on the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw of the Pacific Northwest. The impact of Franziska Boas’s anti-racist methodology is evident in Sullivan’s choreography for works such as Black and Tan Fantasy, 1948, which was performed to the titular Duke Ellington composition with an ingenious burlap and nylon costume supplied by veteran collaborator Jean-Paul Mousseau. Sullivan’s anti-racist gesture resonates with the anti-colonial politics of international surrealist contemporaries unearthed by D’Alessandro and Gale, but it can be traced to distinct sources.

Françoise Sullivan, Triptych, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 123 × 274.5 centimetres. Photo: Guy L’Heureux. Courtesy Galerie Simon Blais, Montreal.

Franziska Boas’s approach to dance as a vehicle for social change channelled the political insights of Indigenous peoples gleaned by Franz Boas while he was conducting fieldwork on potlatch ceremonies in British Columbia. Historian Isaiah Lorado Wilner has recently argued that Franz Boas’s “dynamic vision of humanity as a single, varied, and constantly changing global community” must be traced to Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw influence. As a means of sharing wealth among allies old and new, Wilner argues, the potlatch demonstrates Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw ingenuity in navigating the ravages wrought by colonialism. As an extension of the inclusive politics of the potlatch, Franz Boas’s invalidation of the European concept of “race” reverberates, in turn, in the anti-racist dance pedagogy of Franziska Boas, as well as in Sullivan’s absorption and transformation of these insights in such works as Femme archaïque, 1949. Inspired by a 1945 painting by Mousseau of the same title, Femme archaïque sought “to create a new mythology for women,” writes Lindgren. While in no way derivative of Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw dances, the dynamic vision of social change through cultural reinvention articulated by Femme archaïque can ultimately be traced to Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw inspiration. This line of creative and intellectual influence adds additional nuance to more established narratives that privilege the French anthropologist and surrealist Pierre Mabille’s concept of the “egregore,” or collective mindset, as a blueprint for the Automatistes’ program for cultural revolution.

Françoise Sullivan, À 4 heures du matin I, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 183 × 152.5 centimetres. Photo: Guy L’Heureux. Courtesy Galerie Simon Blais, Montreal.

Although coming to Automatisme later than Sullivan, the work of Abenaki Québécoise artist Rita Letendre undermines linear chronologies by stressing the precedence of Indigenous innovations usually credited to Parisian surrealists. In particular, Letendre’s paintings indigenize the celestial motifs that are a recurring feature of surrealist and Automatiste art. Indicative of this tendency are these lines from Renaud’s Quartier Latin poem: “I brushed against the fire that stars leave behind in their hurried flight,” writes Renaud, “and I felt the burning caress of the moon.” Letendre’s celestial imagery translates the nocturnal poetics of erotic desire articulated by surrealist contemporaries into tense planetary relations that recall the recurring dualisms of Indigenous cosmologies, as discussed by Seneca scholar Barbara Alice Mann. Witness the gestural tensions that animate Letendre’s canvas Entre Mars et Saturne, 1961, in which the titular planets seem to wrestle.

Astral imagery features prominently in Letendre’s high-profile public artworks, such as the now destroyed Urtu, 1972. The propulsive vectors of this hard-edge mural alluded to a constellation visited by a specialized group of Indigenous shamans vested with astronomical knowledge in Algonquian cultures. The artist thereby transformed an existing colonial structure—a lawyer’s office on Toronto’s Davenport Road—into a metaphorical lodge for petitioning the Sky World. Letendre’s decolonial gesture pointedly recalled and indigenized Breton’s rhetorical claiming of a Renaissance hunting lodge in the Czech Republic as the titular “Starry Castle” of the fifth part of L’Amour fou, which was originally published as the stand-alone text “Le Château étoilé” in the surrealist journal Minotaur in June 1936. It was in the pages of Minotaur that Borduas first encountered Breton’s text, which would be decisive in supporting the Quebec artist’s own transition to Automatisme, according to historian Ray Ellenwood. Breton’s act of spinning fiction from a found image of the Czech hunting lodge hearkened back to Leonardo da Vinci’s celebrated practice of imaginatively weaving subject matter from random stains on walls. In effect, “Le Château étoilé” suggested to Borduas how the principles of automatic writing could be harnessed to visual problems. Letendre’s defiant act of overpainting the colonial city with the monumental Urtu overturns Breton’s precedent, countering that the original starry castle was an Indigenous lodge for communicating with the Sky World—not a building in Europe.

In a sense, the work of Thérèse Renaud, Françoise Sullivan and Rita Letendre fulfills André Breton’s prophetic vision of “woman” as the creative redemption of postwar humanity in Arcane 17, the sibylline memoir that he penned while living in exile in the Gaspésie during World War II—and a text brimming with astrological imagery. At the same time, these artists charted artistic paths that have decisively redrawn the official maps of both surrealism and Automatisme.❚

Adam Lauder graduated with a PhD in art history from the University of Toronto in 2016. In 2018, he organized an exhibition on the public art of Rita Letendre at YYZ Artists’ Outlet.