“As we move away from the sun”

A botanical garden, like a museum, is both a sanctuary and an enclosure. Both are committed to the conservation of their contents, which are carefully labelled treasures assembled from around the world. In the case of the garden, glass walls trap the sun’s heat and create an environment hospitable to plants displaced from warmer lands. Like museums, most botanical gardens require an admission fee or a membership. The Allan Gardens in Toronto does not, making it a refuge not just to the plants it houses but to locals and anyone looking for warmth when Ontario’s own sun is scarce. In this way it is an ideal venue for Egyptian curator Fatma Hendawy’s exhibition “As we move away from the sun,” a group show featuring works by artists from Egypt to Chile, exchanging the white cube for the glass house and shifting the logics of both of these sites of accumulation and assembly.

Dima Srouji’s A Recipe for Happiness, 2020, is a study of Saponaria officinalis, or soapwort. An herbaceous perennial plant, with five-petalled pink or white flowers, in Palestine the soapwort has long been harvested for its multiple curative properties, therapeutic and pragmatic; it is used in recipes for happiness, laundry detergent and abortions. The British, utterly disinterested in local customs and rituals of land care, beyond their desire to dismantle them, classified the plant as a weed and attempted to eradicate it. The writer and gardener Jamaica Kincaid has illuminated the link between the botanical garden as we know it and the British Empire’s incessant “need to isolate, name, objectify,” as well as the need to “possess various parts, people, and things in the world.” For empires, knowledge and classification occur in reverse and narrow order— name first in order to possess, then understand later, solely in relation to one’s own interests. “The travelers and ‘experts’ don’t understand,” writes Srouji in a handwritten poem that accompanies found illustrations of soapwort in the Allan Gardens’ tropical house. Together with a delicate hanging embroidery illustrating the plant’s various uses, as inspired by Palestinian amulets, Srouji’s work is an altar to the gifts of the plant, a testament to the perseverance of Indigenous knowledges and a talisman against the wilful ignorance of so-called experts.

Installation view, “As we move away from the sun,” 2024, Allan Gardens, Toronto. Photo: Fatma Hendawy. Courtesy Fatma Hendawy and apexart, New York. Artwork: Abbas Akhavan, you used to call it blue sometimes, 2022, site-specific installation with sound, 23:17 minutes.

In the seventh century BC, Neo- Assyrian King Ashurbanipal commissioned reliefs boasting of his elaborate gardens and orchards in what is present-day Mosul. In a new work entitled Garden Trails, Iraqi-Canadian artist asmaa al-issa has transplanted imagery from the Assyrian palace reliefs—lush palms, figs and abstract floral patterns— onto a series of circular hydrostone tiles. These tiles are site-specific, shaped using moulds from pots belonging to the Allan Gardens, then set directly, one might even say planted, into the earth there. Faint purple, yellow and pink pigments have been absorbed by the tiles from rubbing against the Mexican shrimp plants and purple shamrock around them in the Tropical House. al-issa’s tiles start off as white monochrome, echoing the deep time of Assyrian reliefs, whose original vivid colours have faded away over the centuries since their making. Now the colour creeps back in.

A spikey Euphorbia milii, commonly known as crown of thorns, sits at the entrance to the Allan Gardens conservatory. The same plant grows in Spain, in the shared gardens of the apartment buildings I grew up in, though I never knew its name. Miraculous to find that plant, which grows where arid mountains meet the Mediterranean, surviving on Carlton and Jarvis streets, two blocks from the old Maple Leaf Gardens arena. Kincaid writes about this sense of dislocation and the act of frankly recognizing it: “Oh this is the backyard of someone else, someone far away, someone’s landscape the botanical garden can make an object.” In Toronto the crown of thorns glows, surrounded by Abbas Akhavan’s you used to call it blue sometimes, an installation of coloured film on the glass walls of the greenhouse, which opens the exhibition with an invitation to see the transforming light of the gardens and to become aware of the filters through which we all see.

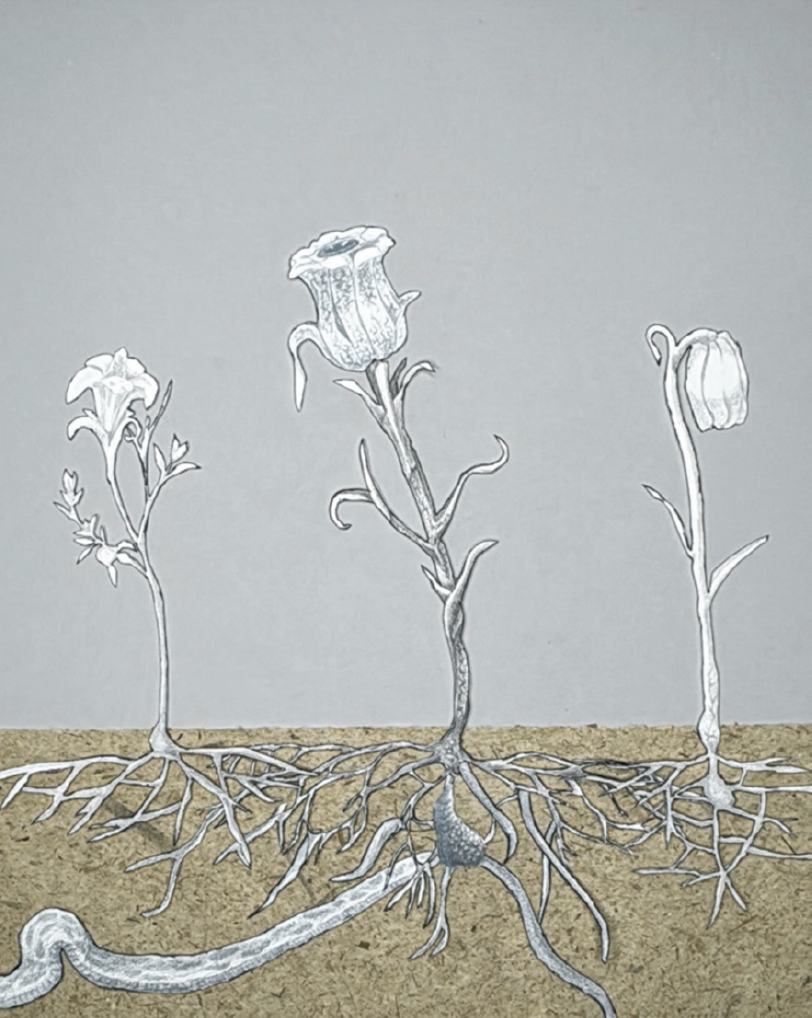

Much more so than the crown of thorns, it is the smell of jasmine blooming on warm nights that reminds me of home. At the Allan Gardens, Lamis Haggag found jasmine, familiar to her from growing up in Egypt. Haggag connects the fragrant white blossoms to the Monotropa uniflora, or ghost plant, native to North America, which contains no chlorophyll and is parasitic, and thus not reliant on the sun for nourishment. Haggag’s stop-motion animation installed at the gardens tracks a jasmine flower’s transformation into a ghost, losing its scent and thickening its nowcolourless skin to survive in this habitat.

Lamis Haggag, A haustorium grows infinitely as the soil takes over (detail), 2024, multimedia installation (stop motion video, 02:30 minutes), dimensions vary. Photo: apexart, New York. Courtesy apexart, New York.

Beyond the insertion of artworks into the space, the exhibition has made the Allan Gardens a gathering place. At the opening Tania Willard held re:FugitiviTea, a ceremony for which she brewed tea made from cedar and bayberry harvested from the conservatory itself, together with yarrow from her home Secwépemc territory. The plants were sewn into a large and fringed cotton tea bag. The tea was brewed in a glazed ceramic vessel created by Myung-Sun Kim and inspired by Korean fermentation crocks. Its immense body and lid were imprinted with images of the yarrow, cedar and bayberry inside. Three semi-transparent banners designed by Willard for the space now hang around the vessel in the gardens. One banner contains text that is both a recipe for making tea and a recipe for viewing or being with artworks: “Take time / Visit long / Prepare / Harvest / Repeat.”

The artworks lie dispersed throughout the gardens, leaving quiet moments for the garden to speak for itself. Most public art installations in unexpected locations act as spectacular and bombastic interruptions that attract an art crowd detached from both the site and the local community; in fact, many such events are funded by developers speculating on property values. In keeping with the history of the Allan Gardens as an historical and present-day site of encampment and protest, “As we move away from the sun” proposes a more long-term commitment to asking how else we might come together to nourish one another, however out of context we may be. ❚

“As we move away from the sun” was exhibited at the Allan Gardens, Toronto, from May 11, 2024, to June 8, 2024.

Georgia Phillips-Amos is a writer from New York City and Málaga, Spain. Her work has appeared in Artforum, Border Crossings, BOMB, C Magazine, Frieze and The Village Voice, among other places. She is a founding editor of the anti-discipline arts magazine O BOD, and currently lives in Guelph, Ontario, with her wife and their two young children.