Artifactotems: Drawings of Ted Barker

The tense that drives the drawn world of Winnipeg artist Ted Barker is the present-past. He has set himself the task of reinventing his grandfather’s life in a wilderness that was already an invention, even while it was being lived. His Opa immigrated to Canada from the Netherlands after the war and found in the Lake of the Woods a place that perfectly suited his sense of self reliance. An engineer by training and a university professor by trade, his summers were spent in a log cabin he built in 1952 with available tools and from trees on the land. “He was an outdoorsman,” Barker concedes, “but he pushed it to the point of being contrived. He wanted everything to be as rustic as possible. He did surveying trips up north where he would buy snowshoes and old rifles, and he filled the cabin with bearskins and traps. He crafted this perfect environment that was almost like a movie set.” The figure of Grey Owl seems to have flown into the camera’s eye.

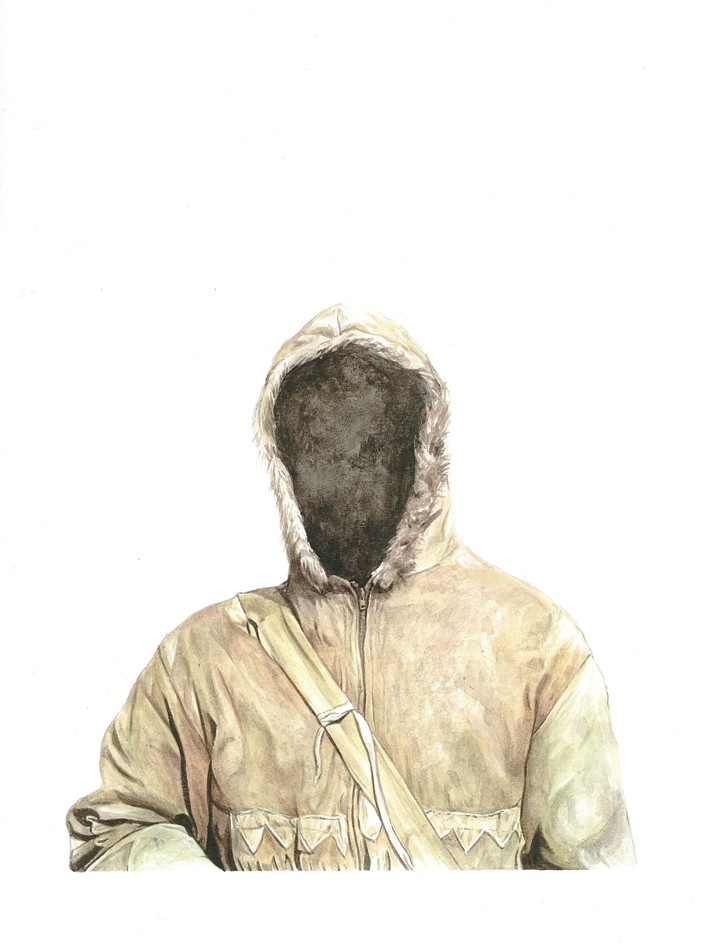

Ted Barker, “Opa’s, coat”, 2012, watercolour on paper, 9 x 12”.

In his drawings, Barker casts himself as ‘best supporting actor’ to his grandfather’s lead role. He works from photographs in which he is dressed in his grandfather’s buckskin coat, sometimes shooting a rifle, at other times simply projecting an arm into space, but always either faceless or looking away from the viewer. The drawings, then, are a curious combination of self-portraiture and a portrait of the coat itself. Barker is not alone in this invention. In Winnipeg, artists of different generations, including Ivan Eyre and Karel Funk, have used unusual head wrappings and deliberate

facelessness to make compelling pictures. Barker is familiar with and admires both.

In all his work, he dresses himself in costumes and replicates things that constitute a ritual of remembrance as well as a way of recovering a lost and innocent childhood. His most recent series carefully renders a number of “neglected and forgotten objects” that remianed in his grandfather’s house after his death: moccasins, decades-old boxing gloves, a pocket knife, an eyeglass, an old Chinese sculpture, even a tooth. All belonged to his Opa and, taken together, they function as a reliquary.

Something in the artist’s devotion to and close observation of this familial past approaches the religious. Most recently, Barker has become attracted to tarps. Their source is, not unexpectedly, the same natural world from which he has drawn both his content and inspiration. Because the family cottage is being expanded, tarpaulins and coverings have been left around the property. They have become his newest costume. “I’m really getting into the tarps right now,” the artist admits. “They are made to keep out the environment, so they represent a barrier between two worlds.” His covering allows him to be in a world of remembered invention at the same time that it allows him to stay out of one troubled by relentless change and loss. Barker recognizes that these tarps are the same “draping, encapsulating cocoon” that he has consistently worn in making his family drawings. There is no question that he is protected inside the surrounding drapery he so deftly captures on the page. But equally determining is the cocoon itself, a form of enclosure that promises, and ultimately delivers, both change and beauty.