“Anna Torma, Istvan Zsako, Balint Zsako”

The Zsako/Torma family fled Hungary as political refugees, settling first in Munich and finally Canada in 1989. Though not always explicitly articulated in individual works, the conditions of exile are inscribed upon their individual artistic practices. A group exhibition at the Wilde Gallery in Berlin this past summer presented recent works on paper by gallery artist Balint Zsako with works by his parents, Anna Torma and Istvan Zsako, both artists with an extensive exhibition history in Canada and abroad.

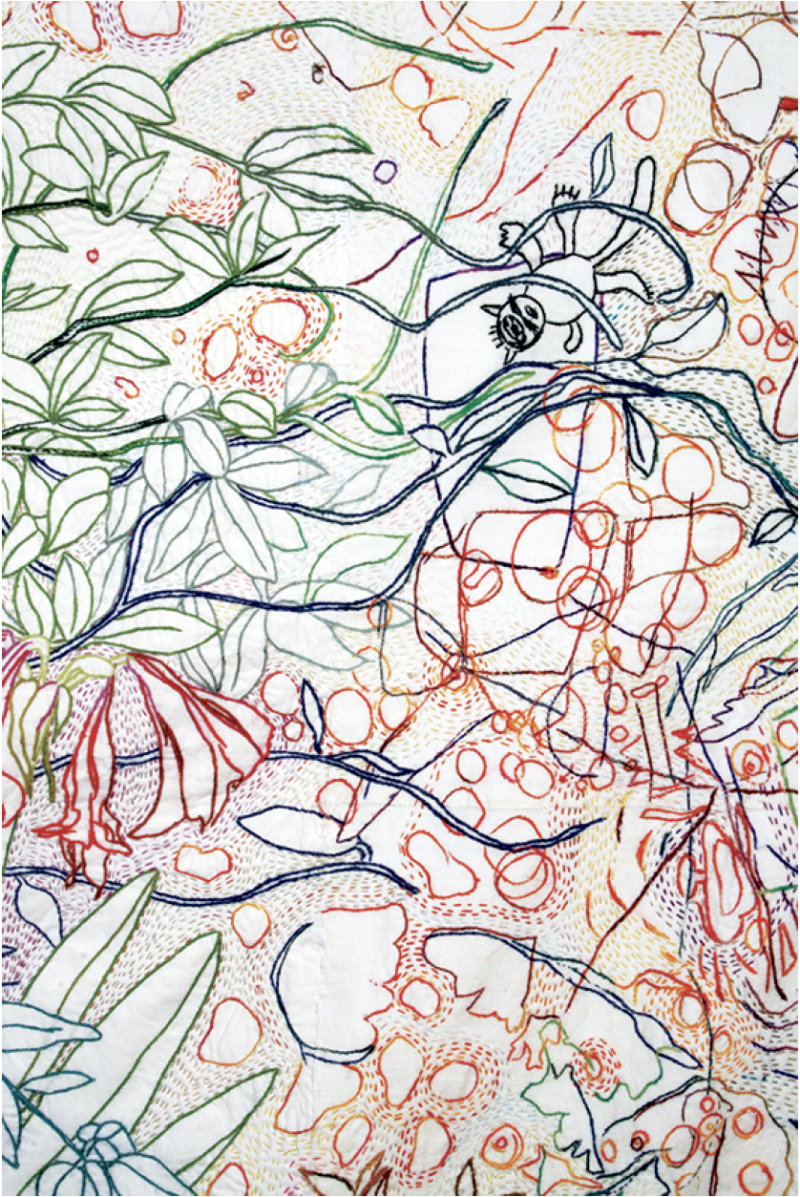

Anna Torma, Draw Me a Garden, (detail), 2006, embroidery, 63 x 53”. Courtesy the artist.

Although the family has exhibited frequently together, they are not a collective. “We’ve had four shows together in the past year, in London, Saint John, New York and now Berlin,” Balint Zsako explains. “We’re always looking at each other’s work and share a certain set of sensibilities even though we rarely critique one another.” While they maintain distinct paths as artists, the complexity of Anna Torma’s textile work, combining sentimental scraps of fabric with childhood drawings by her sons, has doubtlessly influenced several of Balint Zsako’s quaintly Rube Goldbergian erotic watercolors. Likewise, one can see the whimsy of Istvan Zsako’s coy negotiation of the English language in the playfulness that permeates his son’s entire oeuvre.

Living in a cultural diaspora, both directly experienced and realized as a concept, has deeply influenced the work in the exhibition. “There are fundamental aesthetic and narrative similarities in the world,” Balint Zsako said. “For example, ornate textile floral embroideries in China, Mexico and Hungary are extremely similar without having any knowledge of one another. I think it is really fascinating that, given the same materials and similar traditional peasant agricultural cultures, you get stylistic parallels. I try to keep this in mind when I work and hope that anyone can read the stories in my work because the symbols are universal.” He names contemporary influences that include the narrative strangeness of Matthew Barney, the delicate compositional balance of Joan Miro, the organic constructions of Andy Goldsworthy, the totemic sculptures of Louise Bourgeois and the elegant chunkiness of Philip Guston. He adds “some of these references are more obvious than others, but I think it’s this mix of universal and contemporary that is the foundation of my drawings.”

A blend of universal awareness and contemporary conceptual sophistication is what makes this show at the Wilde Gallery so enticing. Despite working in diverse mediums and having distinct bodies of work, they share a deep engagement with narrative tradition and, by extension, the resonance of exile. In Anna Torma’s hands, the form of the quilt becomes a narrative textile collage. Working in the tradition of the Kantha quilt, an ages-old Indian style of wall hanging, Torma combines various cultures with her personal history, creating works from sentimental scraps of fabric, found materials, letters, poems and drawings by her children. In Red Flowers II, organic patterns embroidered in silk and cotton thread are flanked by embellishments of childlike figures and poems.

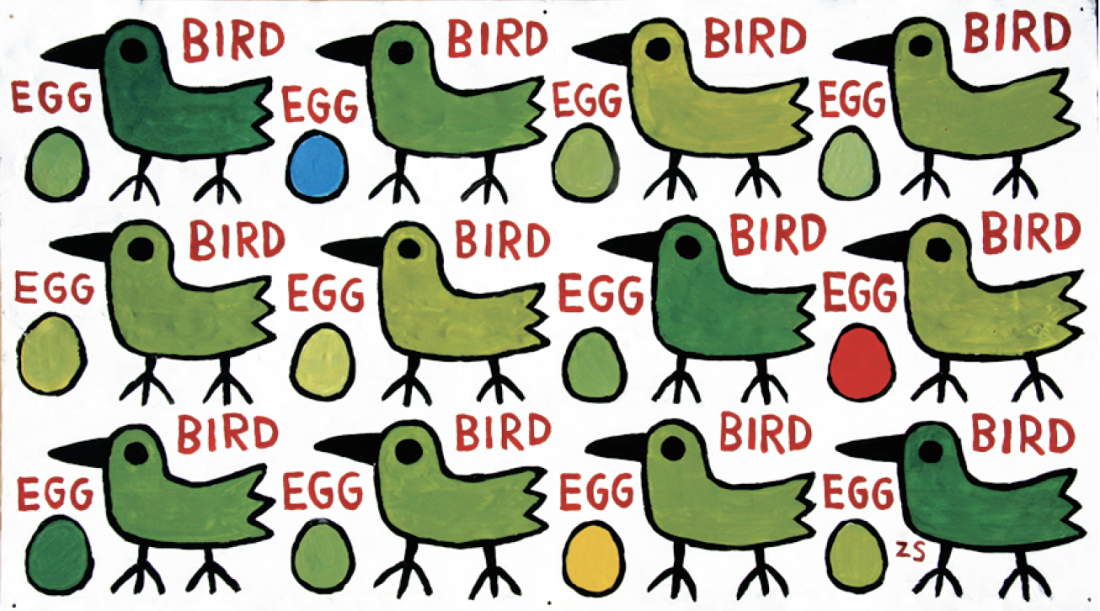

Istvan Zsako, The Question, 2009, enamel on metal, 18 x 24”. Courtesy the artist.

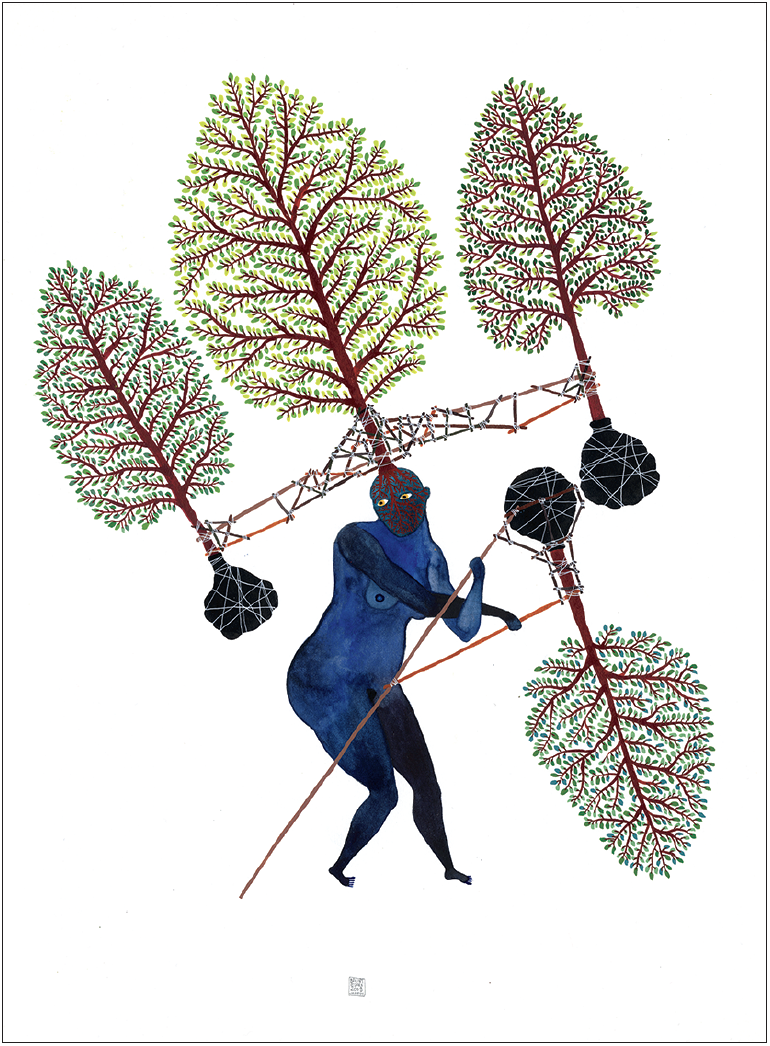

Balint Zsako’s delicately perverse watercolour drawings combine sexually suggestive postures with fanciful organic mechanical appendages. In one untitled work, three figures are huddled in an embrace between two trees with humanoid appendages. As a man reaches out to cup the smaller tree’s breast, an intimate appendage from the other tree reaches out towards the female figure’s ample derriere. The roguish humour that Zsako applies to his surreal watercolours is echoed in the humorous encounters with the English language that his father depicts in a series of small acrylic works. The elder Zsako riffs on comically diagrammatic forms from language textbooks to explicate the absurd and magical process of learning another language and, by extension, another culture. These intimate paintings are an affirmation of non-native speakers’ command of their second language, illuminating its complexity and humour, but also the intimate and idiosyncratic relationship non-native speakers have to their adopted language.

Balint Zsako, Untitled, 2009, ink and watercolour on paper, 16 x 12”. Courtesy the artist.

Edward Said writes in his seminal essay “Reflections on Exile,” “While it perhaps seems peculiar to speak of the pleasures of exile, there are some positive things to be said for a few of its conditions. Seeing ‘the entire world as a foreign land’ makes possible originality of vision. Most people are principally aware of one culture, one setting, one home; exiles are aware of at least two, and this plurality of vision gives rise to an awareness of simultaneous dimensions, an awareness that to borrow a phrase from music is contrapuntal.”

This contrapuntal awareness is felt throughout the Zsako/Torma exhibition. Each family member’s distinct engagement with the idiom of narrative myth, identity and folk traditions is articulated with a self-aware playfulness that is full of heart and devoid of irony. ❚

“Anna Torma, Istvan Zsako, Balint Zsako” was exhibited at the Wilde Gallery in Berlin from June 20 to July 19, 2009.

Jesi Khadivi is a writer and curator living in Berlin where she co-directs the project space Golden Parachutes.