Andreas Gursky

One morning this spring, the German artist Andreas Gursky, whose work receives the highest prices of any photographer alive, walked into the Vancouver Art Gallery wearing Adidas sneakers and a co-ordinated Adidas jacket. In his mid-50s now, Gursky is handsome and fit, crowned with salt-and-pepper hair. He is also mild-mannered, a quality that places him in almost comic relief against the unabashed bombast of his works (and their seven-digit price tags). His arrival launched the only North American installation of the travelling exhibit, “Andreas Gursky: Werke/Works 80–08,” a three-decade survey made up of 130 images—the largest show ever attempted.

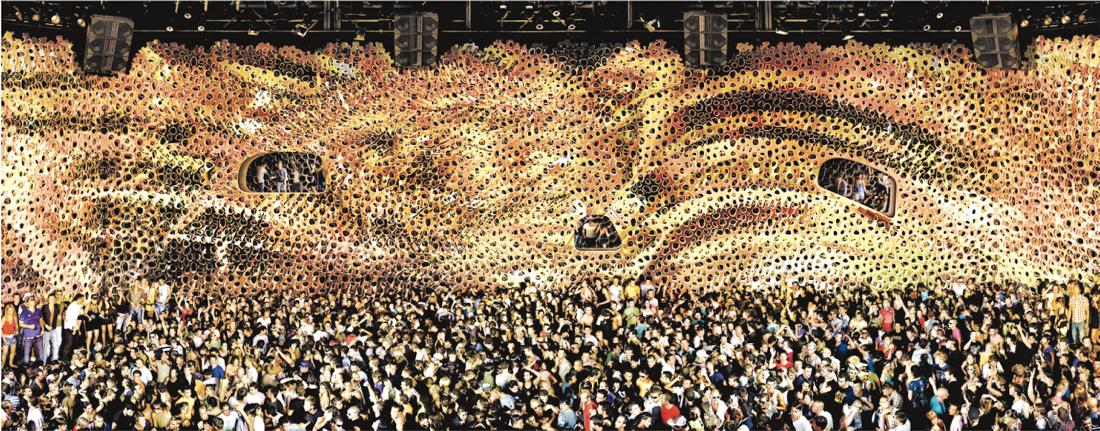

Walking through the exhibit, I found the whole endeavour remarkably apropos. His work is characterized by encyclopedic desires. Enormous and unwieldy human patterns bristle at the confines of even his largest prints. How to contain the kilometres of sunbathers he scans on Italian beaches (Rimini)? How to square off the thousands upon thousands of bullet-precise bodies in a North Korean political rally (Pyongyang I)? Or hold the collected mania of a Madonna concert in a crystal instant? These impossibles are Gursky’s daily bread. Indeed, he can tap the outrageous from seemingly daily scenes, as in his convenience store epic, 99 Cent, which recently broke all records by selling for $3.34 million.

Every gallery is itself a finite parcel of walls; in order to get all “Werke/Works” in, Gursky reduced the scale of most images, lending the exhibit a strained double effect. There is a quality of concession, but something of revelation, too; 09only in the humble proportions of a map do we glean the lay of the land. If Gursky’s images are interested in the big picture, then the “Werke/Works” exhibit is a meta-picture, a bird’s eye view of the career.

Andreas Gursky, Cocoon II, 2008, c-Print, 43.2 x 83.9 cm. © Andreas Gursky / SODRAC (2009). Courtesy: Sprüth Magers, Berlin/London

Stepping off the escalator on the gallery’s third floor, the viewer was greeted by bookends. A prosaic 1984 shot of Sunday walkers near Düsseldorf Airport has none of the pomp or awe that Gursky fans have come to expect. Boys lounge on bicycles, the sky is the grey of a dreamless sleep. But next to this is one of Gursky’s most recent works, a rare self-portrait and one of the few images displayed at gratifying proportions. Untitled XVI is a kind of metallic fantasia; the artist crouches almost invisibly at work in a digitally altered studio space. The main swath of the image is consumed by an organic pattern of steel-coloured cells, a honeycomb out of The Matrix. No two images could be more dissimilar, the one referencing pastoral themes and apparently untouched by digital pixel-tweaking, the other a precise meditation on the artist’s own meditation, and one that even recalls the solemnity of medieval self-portraits with Gursky crouched, attentive, holding in both hands one small corner of the sprawling, amorphous material that swims across the greater space.

Moving with the artist past this sole self-representation, we entered a gallery full of diminished images. How bizarre it seemed to view the monstrous 99 Cent at 43 by 60 centimetres. “I think now, in my new works, I will use many sizes,” Gursky said. He spoke so softly that it was necessary to literally lean in to comprehend, a gesture not normally associated with his wall-sized offerings. He says he’ll have no new shows for the next two years, giving him time to stop and think about scale. “This smaller format makes me rethink the big format. I only produced the big works, maybe, because I had too many museum shows in big spaces. In a way,” he said, “I was accustomed to this.”

His studio is always filled with smaller works, for reference or inspiration. Perhaps the massive self-portrait and Gursky’s decision to mount such an ambitious survey signal a turn from his rapturous signature to something inward, more meditative. There’s almost an expressionistic quality that moves to the fore in these smaller images, as precision gives way to economy of scale. Certainly Gursky has no squeamish adherence to veritas. Even as his works occasionally bear witness to something extraordinary happening. “I think it is my task to document,” he says, and it seems there is simultaneously no qualm about digital manipulation if it delivers the truth to which he wants to bear witness. “I compare my work to the work of a writer. A writer has the freedom to correct different thoughts.” And yet Gursky does see something in the external world that he wants to be faithful to. In Bahrain I, a highly unlikely squiggle of racetrack he came across in the Arabic island country, Gursky grew almost defensive at the suggestion that post-production tampering had been necessary to achieve the chaotic effect. While he conceded to minute alterations, “the character of this place is not my invention. It is the real world—which is important to me.” Similarly, in Klausen Pass, a constellation of figures are spotted over a Swiss Alps mountainside and appear to be tacked on as purposefully as stars on a bedroom ceiling, but Gursky maintains that this is no trickery. What’s on the wall is what he saw that day.

What “Werke/Works” makes abundantly clear is that some humble cropping is necessary for the artist’s view to be wholly digested. The artist holds up a globe. He wants to share, in one moment, a massive, sympathetic understanding. An objective correlative for the uncaught epiphany. ❚

“Andreas Gursky: Werke/Works 80–08,” curated by Dr. Martin Hentschel, was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from May 30 to September 20, 2009.

Michael Harris is an editor at Vancouver magazine.