“An Art at the Mercy of Light: Recent Works by Eli Bornstein” and “Leaves: Rodney LaTourelle

A primer on Structurism might ease your immersion into the cool serenity of Eli Bornstein’s immaculately fabricated, geometric, coloured constructions. If the here and now are your guides of choice, try stretching out on Rodney LaTourelle’s convivial response. LaTourelle’s work, Leaves, was commissioned by the Mendel Art Gallery and is a brilliant pedagogical maneuver, presented simultaneously to help contextualize Bornstein’s work. This is great, classic curating; forget the didactic panels, vinyl keywords and Twitter feeds of viewer responses. Juxtapose instead: this art tells me about that art. Lie back on LaTourelle’s coloured panels and meditate on light or social relations or…drop some acid and smell the colours.

The first point to note is scale. Although Bornstein’s work calls for a total baptism into colour, light and abstract form—it’s small. The sculptures-in-the-round sit on plinths and the planar, wall-mounted pieces are easel-sized. Neither painting nor sculpture, these constructed reliefs fuse abstract form and colour—in space. But not lived space. In fact, the modest, yet still publically proportioned main gallery of the Mendel reinforces the domestic scale of Bornstein’s art. The result is an evocation of an earlier age of radical modernist innovation, before the Americans super-sized their work to fit the spectacle-producing presentations of the contemporary museum.

Eli Bornstein, Quadriplane Structurist Relief No. 8, 2001–02, acrylic enamel on aluminium. 76.4 x 135.8 x 16.2 inches. Collection of Eli Bornstein.

LaTourelle’s work, on the other hand, takes its cues from bodies, buildings and public space. Witness mothers and daughters, 20- somethings and older guys lying about, sitting cross-legged or sneaking unauthorized leaps from one coloured recliner panel to the next. Rodney LaTourelle is an artist who has a Masters degree in landscape architecture but the real difference in scale-sensibility is generational. Installation, site-specificity, the advent of public art and its attendant hospitality have all changed the implicit assumptions that inaugurate the institutionalized leaps of faith that allow for shared experiences of art. One of Bornstein’s and his Structurist colleagues’ explicit innovations was the fusion of painting and sculpture, however the particular attention to the scale of the lived world was never really embraced or problematized, except in specific public commissions. But times change and spectacle and participation are the new real, and even with some historicist slack there’s still a tenacious lone-wolf temper to the Structurist project. It’s an avant-garde thing. Donald Kuspit noticed it in 1977 when he reviewed a retrospective of one of Bornstein’s closest colleagues, Charles Biederman. Referencing one of the great theorists of the avant-garde, Renato Poggioli, Kuspit wrote in Art in America (vol. 65 no 3): “[Biederman attempts to possess] the future [as] a way of legitimizing present artistic activity.” In his own book, The Theory of the Avant-Garde, Poggioli wrote that in an extreme form “[the avant-garde] no longer heeds the ruins and losses of others and ignores even its own catastrophe and perdition. It even welcomes and accepts this self-ruin as an obscure or unknown sacrifice to the success of future movements.”

Both Beiderman and Bornstein were uncompromising in the production and discursive promotion of their very particular brand of non-objective art. They were resolute in distancing themselves from their abstractionist contemporaries. Both lived and worked in the margins of the art world (Red Wing, Minnesota and Saskatoon, Saskatchewan respectively). Once they hit upon their artistic métiers they became lifelong devotees to a circumscribed field of aesthetic possibilities. Both Biederman and Bornstein held fast to the belief that their artistic and theoretical work, their understanding of the visual world and their sense of art-historical progress would eventually be absorbed and promulgated.

Eli Bornstein, Installation view of “An Art at the Mercy of Light: Recent Works by Eli Bornstein,” Mendel Art Gallery, 2013. Photograph: Troy Mamer.

For 50 years, the University of Saskatchewan contributed to the publication of an art journal devoted to Structurism. Bornstein was its sole editor and consistent contributor, both in articles and in reproductions of his own artwork. Heading and teaching in the University of Saskatchewan’s Department of Art and Art History for most of those years, he was given a remarkable degree of freedom to pursue his interests. This could be seen as self-defining obscurantism but a more generous reading would regard Bornstein, his colleagues, his school and the magazine as a strange and exotic gem. Over the years The Structurist, (Canada’s longest, continually published art journal running from 1960–2010), hosted a number of well-respected writers and artists including John Berger, Suzi Gablik, George Woodcock, Stan Brakhage and Erwin Panofsky. Other contributors were less familiar. This free-ranging, cross-disciplinarity, editorial partisanship and the magazine’s high production standards combined in an eccentric and contradictory marriage of blue blood and outsider perspectives.

In 1961, for the second issue, Bornstein published an article by Kyoshi Izumi, a Regina architect who wrote about his experiments with LSD for research into the “perceptual world of the mentally ill.” The author describes new synesthetic relations (“confusion” is his word) between texture and temperature, sound and colour, smell and colour. A few years later, Izumi gained some notoriety for his contributions to the sympathetic design of psychiatric hospitals. It’s to Bornstein’s credit that he supported this kind of experimentalism, and it reveals his own aesthetic preoccupations with the phenomenology of colour. Another preoccupation, surprising, given the geometric and machined look of his work, is Nature.

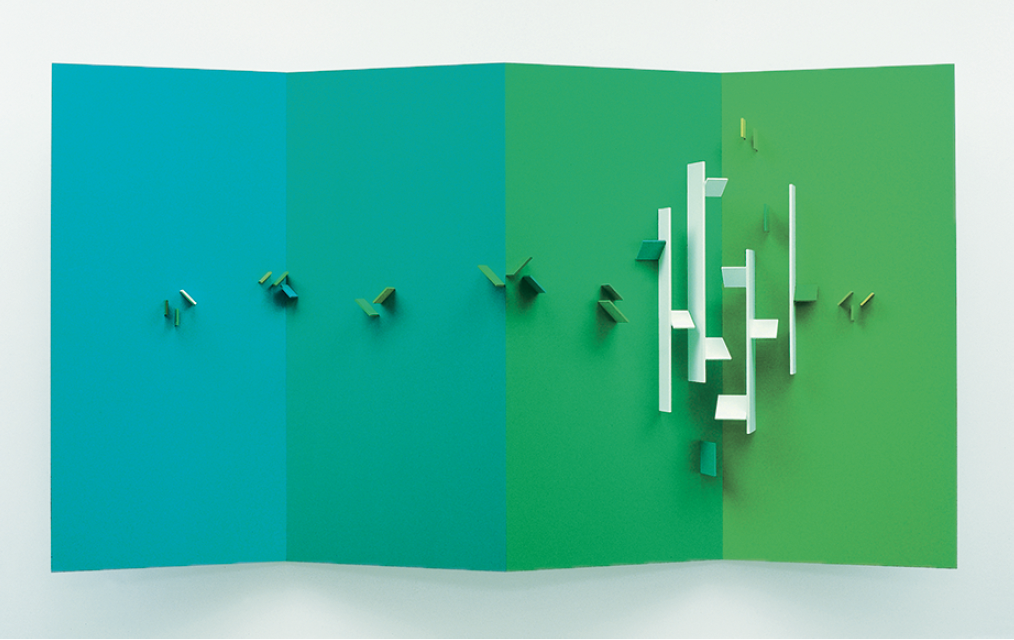

Rodney LaTourelle, Leaves, 2013, 25 modular units with steel bases and wooden panel inserts, powder-coated and painted steel, plywood, lacquer, auto body paint, dimensions variable, site-specific installation, Mendel Art Gallery. Collection of the Mendel Art Gallery. Photograph: Troy Mamer.

The exhibition’s curator, Oliver Botar, addresses Bornstein’s theoretical position on the relations between art (specifically abstract art) and Nature in his catalogue essay. Botar positions Structurism within a larger “biocentric” trajectory in Modernism—itself a subset of 19th century Neo-Romanticism and the proto-environmentalist transcendentalists. In fact, as he rightly points out, there is no necessary relation between aesthetic ideology and style. Precise geometry may very well stand as a sign for, or open doors to, the organic. While Canadian non-objective pioneers Lawren Harris and Bertram Brooker may have been too local to make it into The Structurist, in spite of shared aesthetic projects, the Russian and Eastern European constructivists certainly do. Botar cites László Moholy-Nagy, op art and the Californian Light and Space artists including James Turrell as the acknowledged models for comparison.

Whereas abstraction was considered “entropic,” the idea of construction could be construed as generative. The final issue of The Structurist was framed by a strikingly contemporary, post-humanist subtitle: “Toward an Earth-Centered ‘Greening’ of Art and Architecture.” The buzzingly relevant, ecological theme of this final volley was actually quite consistent with the aesthetic perspective Bornstein had promoted from the first issue. There, he distinguished his school of abstraction from the “anti- or non-historical outlook” of the Expressionists. In his first essay for the journal, he laid out a dichotomous art history that forked off into two incommensurable paths from Cezanne on. On the one side were the Post-Impressionists, the Symbolists, the Fauvists, the Dadaists, the Surrealists, the Abstract Expressionists, the Automatists and the Action Painters. These practitioners and apologists were “anthropocentric” and displayed “a total disengagement from the temporal processes of historical as well as social life. [They did] not wish to be entangled in dealing with relatives, the relatives of history, of society, etc. [They represented] an attitude of dis-affiliation,” Bornstein wrote in the first issue.

Rodney LaTourelle, Leaves, 2013, 25 modular units with steel bases and wooden panel inserts, powder-coated and painted steel, plywood, lacquer, auto body paint, dimensions variable, site-specific installation, Mendel Art Gallery. Collection of the Mendel Art Gallery. Photograph: Troy Mamer.

According to Bornstein, what the Expressionists were primarily disaffiliated from was Nature—sublime, ever changing but obdurate. Without a vigilant and steadfastly subservient eye on this objective truth, artists, he maintained, tended to distract themselves with “the psychological, the unconscious, the irrational, the sensuous, subjective, internal man.”

On the other side of the great divide were the Cubists, the Neo-plasticists (de Stijl), the Suprematists, the Constructivists (in that order), all of which culminated in Structurism. Bornstein’s was a flagrantly dualistic and evolutionary history, and in that sense Structurism is unabashedly progressive and typically modernist.

Yet the unrelenting adherence over the years to an ecologically rooted, almost Gaian conception of Nature as the proper wellspring and ultimate subject of art reveals a very contemporary, even visionary perspective. Bornstein’s art and the art-theoretical niche he carved out for Structurism emanated from an abiding devotion to developing visual analogues to what we now might call the rhizomatic. There are non-hierarchical and anti-narrative relations between artworks within his own oeuvre; comparisons with colleagues are similarly lateral. Each work may be taken as an ongoing reiteration of the Structurist program—a kind of virtual multiple. The cross-disciplinary focus of the magazine and its writers is similarly non-hierarchical.

Perhaps Rodney LaTourelle’s “Leaves” is a Structurist work, but as a socio-spatial intervention it sides more with installation than painting or sculpture. Viewers are encouraged to sit or lie on it—and they do. And maybe that’s the most significant comparison between two artists whose work is so dependent on the careful articulation of formal relations. Bornstein’s art is purely visual. Your imagination is the catalyst, but “An Art at the Mercy of Light” is for your eyes only. “Leaves,” on the other hand is activated through social interaction: it’s convivial—go ahead and touch it, sit down and look for your keys, strike a new committee, or just drop out.

“An Art at the Mercy of Light: Recent Works by Eli Bornstein” and “Leaves: Rodney LaTourelle” were exhibited at the Mendel Art Gallery, Saskatoon, from June 14 to September 15, 2013.

Marcus Miller is Director of the Gordon Snelgrove Gallery at the University of Saskatchewan. He is a curator, teacher and critic.