“ᐊᕙᑖᓂᑦ ᑕᒪᐃᓐᓂᑦ ᓄᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᓂᑦ // among all these tundras”

The poem “My home is in my heart,” by famed Sámi poet Nils-Aslak Valkeapää (Áillohaš), opened the exhibition “ᐊᕙᑖᓂᑦ ᑕᒪᐃᓐᓂᑦ ᓄᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᓂᑦ // among all these tundras” at the Esker Foundation this past summer. The title, a line drawn from the poem, brings the reader and viewer directly into the world and nomadic existence of Indigenous people of the circumpolar North.

… that I cannot live in just one

place

and still live …

among all these tundras

The lines from Áillohaš articulate Inuit, Alaskan and Sámi peoples’ facing the impossible task of translating their experience of the land, selfhood, sovereignty and culture to the arriving settlers, as the colonizers occupied their homeland. Curated by Heather Igloliorte, Amy Dickson and Charissa von Harringa, the exhibition featured work by 12 artists with roots in the Arctic. The sovereign acts taking place throughout the exhibition referenced the body and its presence, language as an act of resistance and reclamation of land. These themes became sites of knowledge and radical decolonial action. Through these unfolding dialogues, critical moments of understanding, contemplation, recognition and acknowledgement are opened for visitors to the exhibition.

Couzyn van Heuvelen, Qamutiik, 2014, industrial found wood pallets. Courtesy the artist. Images courtesy the Esker Foundation, Calgary.

In framing the exhibition through poetry and language, the curators pinpointed the salience of language, storytelling and oral history in Indigenous culture. Opening the exhibition through the words of a Sámi writer flips the narrative by pointing to the attempts by the colonizers to eradicate Indigenous languages. To set foot within the space through the words of Áillohaš is to perform a decolonial act, an act of recognition towards the sovereignty of Indigenous language, thought, experience and existence.

The body acts as a point of departure for Inuk artist Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory. Her video, Timiga, Nunalu, Sikulu (My Body, the Land and the Ice), 2016, uses her body as a location for resisting and challenging the colonial, eroticized male gaze. The artist is seen from behind, an odalisque-like figure set against a glacial landscape. The scene is charged by the viewer’s gaze as Williamson Bathory seemingly offers her body as the location for engagement. However, when she turns to the viewer and holds our gaze, the message becomes one of resistance, focusing on her identity as an Inuk woman. The artist appears passive but instead engages the audience through making herself present—living and being in her landscape proudly and unapologetically, connecting with the viewer, reclaiming her identity by using her body as the site for translating aspects of her Inuit and female identity.

Marja Helander, Dolastallat (To have a campfire), 2016, video still. Courtesy the artist.

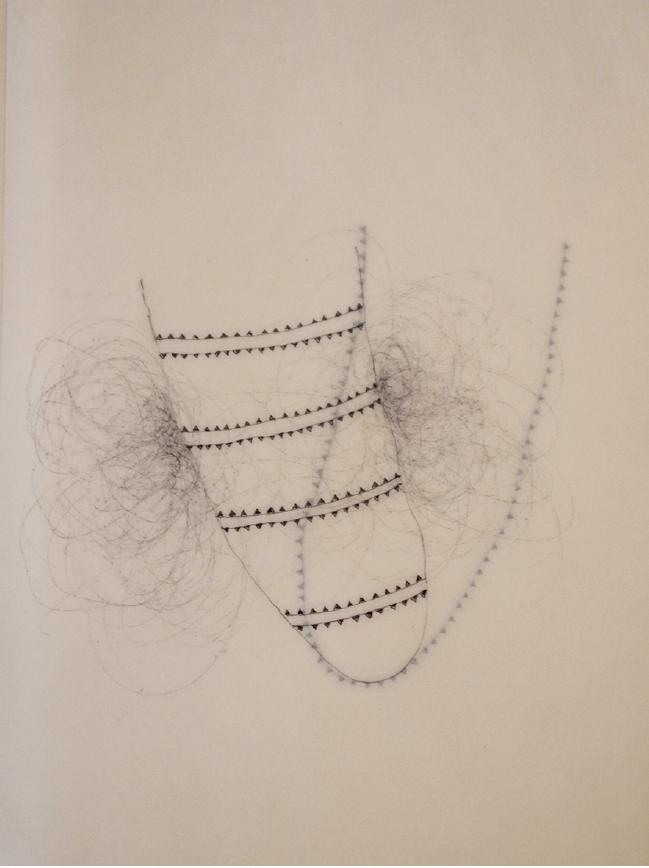

Alaskan artist Sonya Kelliher’s Combs’s Secret Portraits (ink, pencil, beeswax on paper, 2018) presents a series of drawings, portraits of amorphous shapes—open and welcoming, disturbing and lonely, vessels for containment and sites of acknowledged vulnerability. The drawings are layered through her drawing on both sides of the paper, which is then dipped in wax. They appear opaque, recalling the body, the paper resembling the suppleness of skin. Through gestural marks that are stitch-like, Secret Portraits suggests untold truths, becoming a sacred space for holding stories that need not be told. The pouch-like forms connote the traditional walrus tusk shape found on either side of the traditional parka. The portraits, corporeal in nature, worn over the body and covering the heart, shield the secret bearer while simultaneously empowering them.

Language as an act of resistance is present in the work of Allison Akootchook Warden. An Iñupiaq artist from Alaska, she utilizes the Iñupiaq language as a tool to tell her story. In the piece siku siku, part performance, part sculptural installation, the artist tells an intertwining tale, that of her path versus the path of a cousin who became addicted to methamphetamine, or “ice” (siku) in its slang form. Akootchook Warden verbally references the central place ice holds for people of the Arctic regions, as well as the social issue of meth addiction, giving voice to both stories. She also inscribed the words of her performance onto a plinth, which was left in-situ. By sharing Iñupiaq with viewers, she is reclaiming her language, creating and leaving a residual site of resistance in the gallery.

Laakkuluk Williamson Bathory, Timiga, Nunalu, Sikulu (My Body, the Land and the Ice), 2016, video still. Video by Jamie Griffiths, music by Chris Coleman, featuring vocals by Celina Kalluk. Courtesy the artist.

The land surfaces and intermingles in the works across the exhibition and the cited themes, providing an equally compelling platform to discuss resistance and radical decolonial action. Inuk artist Barry Pottle’s photographic series “Foodland Security” (digital ink-jet prints on archival paper, 2012) references country food and its preparation. Indigenous people lived off the land, their stories shared over generations, carrying knowledge for survival. With the arrival of settlers and the instigation of colonial law, Indigenous traditions were largely eradicated. By highlighting the resurgence of country food, prepared and enjoyed by the urban Inuit of Ottawa, the work presents itself as a sovereign act of resistance to colonialism. The photographs not only document but also keep Inuit practices alive through the lens of an urban Inuk, demonstrating a radical act of reclamation.

Iqualuit- and Ontario-based Inuk artist Couzyn van Heuvelen’s sculpture Qamutiik (industrial found wooden pallets, 2014) is a replica of a sled that was used in the North before the introduction of the snowmobile. According to the artist, pallets are ubiquitous in the North. In his practice, van Heuvelen considers traditional Inuit tools and technologies, how materials he comes across in his hometown were once used compared with how they are used now. The sculpture refers to a traditional form of transportation for Inuit people and the impacts of colonization. During a period of colonial resettlement in Nunavik and the Baffin Region between 1950 and 1970, the Inuit of that area were not only resettled into central communities, but their sled dogs were systematically killed by the RCMP in what was purported to be a new government-sanctioned policy. Qamutiik cites the sled as a symbol of Inuit independence pre-settlement and a tongue-incheek reference to an object’s being rendered obsolete.

Sonya Kelliher-Combs, Secret Portraits, 2018, ink, pencil, beeswax on paper. Courtesy the artist.

“ᐊᕙᑖᓂᑦ ᑕᒪᐃᓐᓂᑦ ᓄᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᓂᑦ // among all these tundras” became a space of resistance and decolonization, a space of recognition of Indigenous issues and settler colonialism, but above all a radical and sovereign act towards honouring, recognizing and celebrating Indigenous identity, politics and sovereignty, in particular for settler and ally Canadians. The exhibition essentially demanded that settlers and allies reinvestigate their own colonial presence while learning and acknowledging Indigenous resistance and reclamation of culture, traditions, land, languages and existence. ❚

“ᐊᕙᑖᓂᑦ ᑕᒪᐃᓐᓂᑦ ᓄᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᓂᑦ // among all these tundras” was exhibited at the Esker Foundation, Calgary, June 1 to August 30, 2019. It was on view at the Onsite Gallery, Toronto, from September 18 to December 7, 2019. The exhibition is produced and circulated by the Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery, Concordia University.

Maeve Hanna is a settler and ally writer based in Calgary, AB. In spring 2020, she will begin a MFA in Creative Writing at Naropa University and the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics (Boulder, CO).

To read the rest of Issue 152, order a single copy here.