All That Has Value, Eating up the Americas

What is designated, here and now, by the Americas? What do those restless reconfigurations of nature and culture add up to (or subtract from) at a time when local, regional and national distinctiveness are subject to the needs of transnational capitalism? Clearly, answers to such questions ought to be found in artistic as well as political and economic practices, especially when the 1995 Whitney Biennial includes for the first time work by non-American “NAFTA artists” (Stan Douglas and Jeff Wall from Canada; Julio Galan and Gabriel Orozco from Mexico). The curator of the Whitney show, Klaus Kertess, seems content to understand the vanishing of borders and a new internationalism as an opportunity for us all to become Americans. Such direct paternalism at least has the merit of reminding us that art is neither free from nor entirely captive to geopolitical realities and the demands of the marketplace. But of course not everyone, either inside or outside the United States, would share Kertess’s sense of border crossing as benign assimilation.

Ron Benner is a case in point. His most recent exhibition employs a variety of strategies to bring home the historical and current complexities of contact, exchange, dependency and consumption. He moves across various natural and cultural terrains and within three communities: Culiacan, Sinaloa (Mexico), Immokalee, Florida and London, Ontario.

A self-styled “survivor” of the Agricultural Engineering programme at the University of Guelph (he lasted a year before deciding in 1970 to become an artist), Benner has over the past two decades continued to educate himself about the history, politics and science of food production. He has drawn inspiration not only from the indigenous peoples he’s encountered during his travels in the Americas but also from the work of activists who monitor the effects of concentrated corporate ownership on traditional cultivation methods and biological diversity. Having taken his work to Spain in 1992, Benner continues to use discovery and conquest as both theme and method, showing how strong is the desire to manage diversity and control value, whether understood as labour, transportation, marketing, consumption, ‘pure’ profit or ‘pure’ art. Benner claims neither the detachment of the outsider nor the privileges of the insider; he insists rather in subjecting notions of inside and outside to permanent interrogation. The effect of his questioning is to reveal how we are all implicated in the processes of cultivation (in every sense of that term). Beyond that it indicates our responsibility as producers, consumers, etc.—for the fate of all sorts of native species brought to traditional or newly penetrated markets.

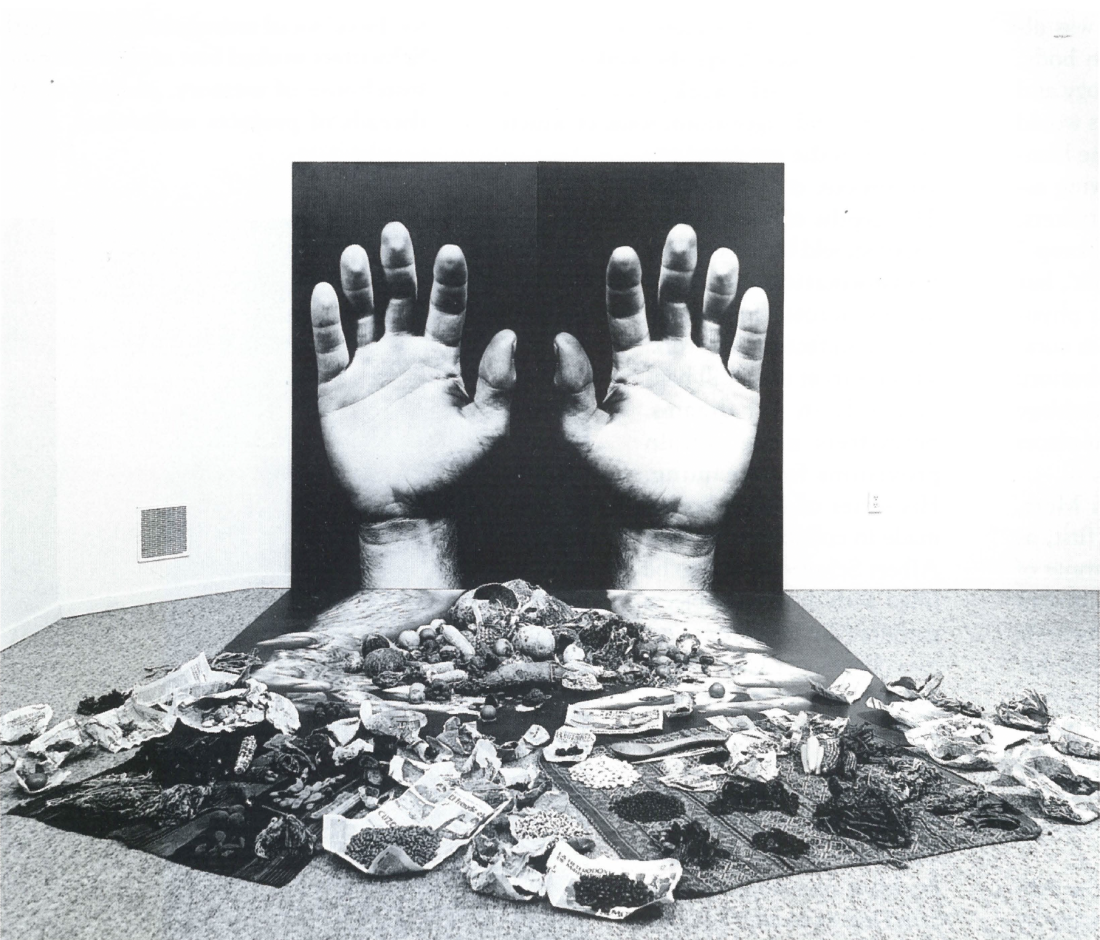

Ron Benner, And the trees grew inwards—for Manuel Scorza, 1979-1980, mixed media photographic installation, 7 x 7 x 10’. Photographs: John Tamblyn.

Benner relies on a set of installations which will be differently set up in different exhibition and commercial spaces. In London, at the McIntosh Gallery on the campus of the University of Western Ontario and at the century old vegetable market downtown, Benner reworked distinctions between gallery-goer and shopper. One work lists plants native to the Americas and comments quietly on the power and limitations of print as a medium for botanical taxonomy and on the connections of science to development. At the same time it incorporated qualities of the commercial hoarding and the war memorial. But how can any art work compete with virtually constant noise and bustle? The question arose again inside the market where ten double-sided panels hung above colourful stalls, offering a black and white photographic history of how Ontarians get their greens in winter and their more exotic peppers year round. Benner does not try to compete with quotidian patterns of movement and attention. Wisely, he goes with the human flow in order to insinuate the idea of the market as a (potentially educational and ethical) pause between gathering and dispersal, producing and consuming. This insinuation might be utterly lost in the chilly efficiency of a suburban supermarket, but it enjoys a deliberately modest success in a site which favours small family businesses while presuming a habitable city centre.

When Benner moves from commercial to curatorial space his idiom, while never self-righteous, becomes more assertive and confidently aesthetic. Assured of more informed and intense attention from a gallery audience, he requires the viewer to consider six installations in the context of the new work that gives the show its title. In the gallery we first encounter two posters of watercolour paper stained red and bearing blue grey lettering. They are situated on the wall above a small table under which there is a photograph of a supermarket shopping cart in motion. The posters feature English and Spanish translations from Nahuatl, recording an indigene’s description of what the earliest European conquest meant for native culture: “all that has value was then counted as nothing.” This statement amplifies its meaning as we move through the exhibition. Benner uses the dramatic tensions of language to remind us of the hazards of translation of any kind, and of the fact that our impressions of conquest are skewed by the apparatus of dominant cultures. But there is an important and encouraging reversal here too. Imperial powers treated indigenous artefacts too often as so much raw material, to be blithely applied to a distant monarch’s debts or the decorative needs of church and state. Benner uses a revisionary materialism to refashion the meanings of conquest, then and now. He deliberately depends on the ‘raw’ or archaically processed materials of indigo and cochineal to colour and define his chosen text. He uses their rich history and visual power to unsettle any notions of modernity derived from distinctions between primitive and advanced communications technology, natural and synthetic materials, basic resources and ‘value-added’ products. This installation, with its discreet allusions in the age of NAFTA, to what is on the table and what is under the table, along with its disciplined evocation of rapacity and resistance, produces an ironic field of possibilities rather than a strident or naïve sermon. Benner strives for multiple and unstable effects at every point, linking elegy to energy, wisdom to science. In the process he rehabilitates indigo as more than “the king of natural dyes” that ‘made’ the Carolinas and cochineal as more than “a non-carcinogenic red for simulated crab and lobster meat.”

Ron Benner, Under Digestion, 1995. Installation at Covent Garden Market.

These issues had been broached earlier in another work in the show, Trans/mission: Drought Simulation (1988-1991) which replicates an experiment at the University of Guelph and critiques it by linking it photographically, materially and geometrically to Peru. The alliance between agribusiness and science comes across as uncannily alien and bereft of human content, while traditional practices assert themselves in an ironic allusion to temple architecture and decoration in the form of a collapsed pyramid of Idaho bakers wrapped in gold foil. Transmission proves to be as mixed as translation, a point reinforced in Trans/mission: Thanksgiving (1991-1994) another installation employing black and white photo-murals to play provocatively with historical sequences. Benner uses other people’s images—in this case they include a detail from Benjamin West’s The Death of Wolfe (1771) and Robert Frechette’s photograph of the citizens of Châteauguay pelting police with vegetables during the Oka crisis—to play down originality and property rights and to emphasize the interconnected production of meanings that define individuals as well as communities. The specifically Canadian content of this work is only too readily connectable to the violent themes of And the trees grew inwards—for Manuel Scorza (1979-1980), with its haunting combination of human hands with the produce and detritus of contemporary Peru, and with Cuitlacoche—in memory of Michel Foucault (1985), where the high-priest of deregulated desire seems to smile in phallic wonderment at corn cobs both enhanced and disfigured by an edible fungus.

The final work in the show, In Digestion (1993-1995) is both more and less ‘impressive’ than the other installations, and deliberately so. Benner reasserts, if not the banality of evil, at least the ordinariness of exploitation. The viewer moves past a 17th-century map of Le Nouveau Mexique et La Floride, as well as stacks of brightly coloured produce boxes, seven in a controlled progress through a rubber curtain into the simulated interior of a truck. Tire shards, galvanized sheetmetal smeared with tomato paste, and more than 200 carefully sequenced photographs connect workers in the southern fields to consumers in the north. In such variations on the themes of taste and imaginative transport, does art thus relapse back into agitprop, as some viewers were heard to ask with a mixture of panic and disdain? One of the values of this endlessly provocative show is that it asks us to situate that distinction along a continuum of experience and accountability where location is, as they say, everything. ♦

“Ron Benner: All That Has Value” has been exhibited in London, Ontario and in Vancouver. It will also tour to Edmonton and Regina in 1995.

Len Findlay contributes to Border Crossings from Saskatoon where he directs the Humanities Research Unit at the University of Saskatchewan.