Alex Katz

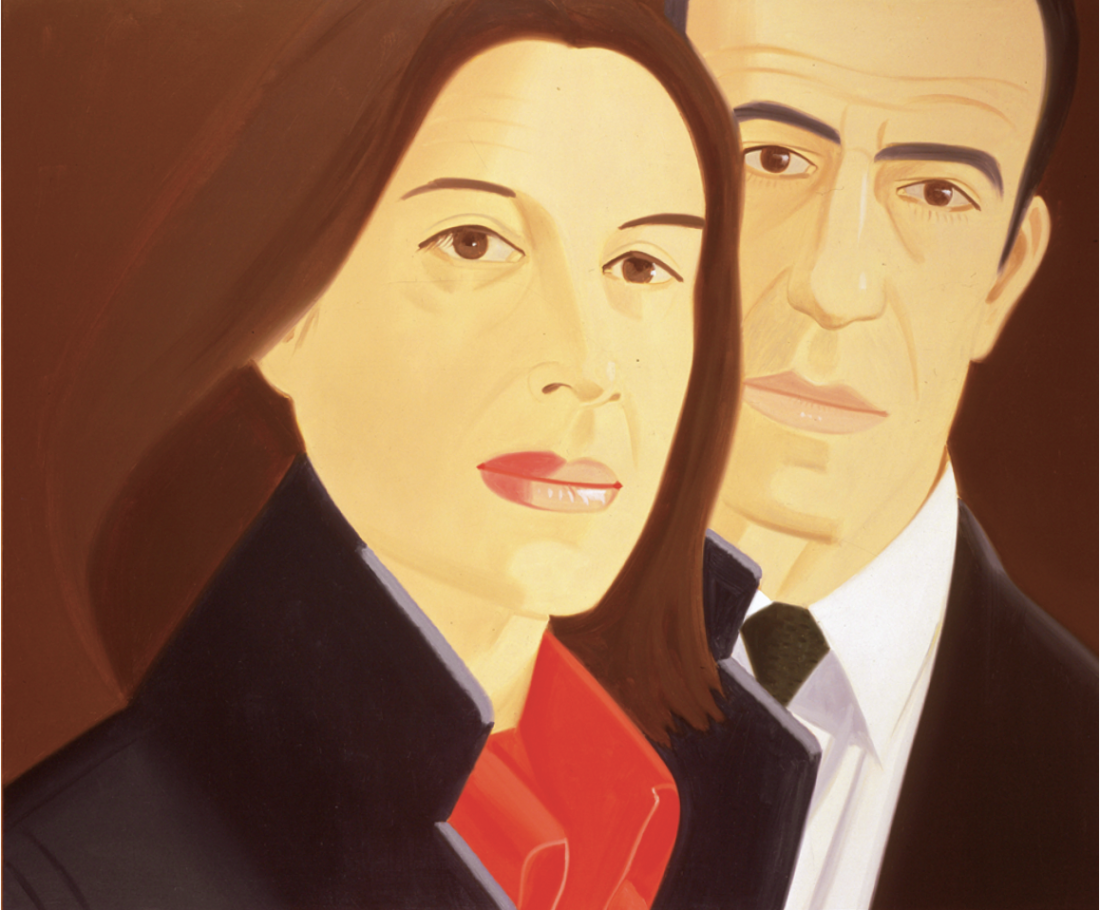

Alex Katz, Ada and Alex, 1980, oil on linen. Collection of Joan and Adan Safir. All photographs by Vivien Bittencourt / Courtesy Pace Wildenstein, New York.

For more than half a century, portraiture has been central to Alex Katz’s painting (but by no means its only subject), and his pictures of Ada, his wife and favourite model, have been central to this body of work. The 34 Adas (from the more than 300 executed by Katz from 1958 to the present) on view at the Jewish Museum allow us to trace the development of his wide-ranging portraiture and assess its contribution to recent painting.

In the 1950s, Katz was the primary innovator of the New Perceptual Realism, which revived then-moribund figuration. In the early 1960s, he was the first realist artist to adapt “the big picture” associated with Abstract Expressionism and hard-edge and stained colour-field abstraction to Realist painting, enabling his work to hold its own against abstract painting and rivalling it in visual impact, muscle and grandeur. Katz’s ongoing aesthetic mission has been to create representational paintings that make no reference to received and outworn styles, manners or visual ideas. Over the years he has kept his painting contemporary.

Alex Katz, Blue Umbrella #2, 1972, oil on linen. Courtesy Peter Blum Gallery, New York.

At the start of his career in the early ’50s, Katz painted figurative portraits in a gestural manner, but in the middle of the decade he reduced the active brushwork— never too brushy to begin with—in order to portray his sitters with greater accuracy. In part, he was reacting against the prevalent avant-garde-style, de Kooning-esque, action painting, whose smudged and smeared, often slapdash facture he felt would blur the features of his human subjects. Action painting, both abstract and figurative, moreover, had come to look enervated and dated—in a word, academic. In rejecting painterly drawing, Katz, with an eye to Matisse and Rothko, increasingly relied on the interaction of flat planes of colour to produce convincing representations of his sitters, as in Ada with White Dress, 1958. In the early ’60s, with The Walk 2, 1962, for example, he further smoothed the surfaces and sharpened the edges of his forms. In short, Katz, then and since, has synthesized two seemingly irreconcilable qualities in figurative art—that is, truth to the look of his three-dimensional subjects and truth to the painting as a two-dimensional surface.

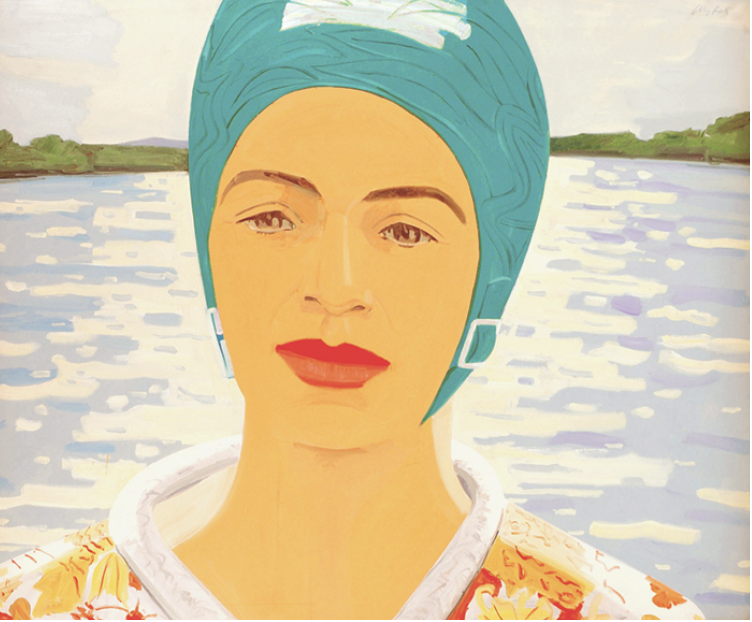

Alex Katz, Ada with Bathing Cap, 1965, oil on linen. Collection Paul J. Schupf, Hamilton, New York.

Intent on rendering the literal appearances of his sitters, Katz does not intentionally interpret their psychological states, although he occasionally has; the anxious Ada in the Park, 1965, comes to mind. On the whole, his portraits appear “cool.” As he has said, in order to “stress objectivity, a certain impersonality creeps in. Objectivity and impersonality are words that link naturally.” But, if Katz rarely probes beneath the surface of his subjects, he does express the roles they play in life. Thus, in different portraits, Ada appears as woman, wife, mother, muse, sociable hostess, celebrity, myth, icon and New York goddess. As Katz’s son Vincent observed, his mother is an icon-like Madonna in Ada and Vincent, 1967, and a lover in Upside Down Ada, 1965. In Ada and Alex, 1980, she is a stylish wife; in Blue Umbrella, 1972, an all-American girl; in Ada’s Night, 1998, a glamorous New York sophisticate; in Red Coat, 1982, a fashion model; and in Gray Day, 1990, a celebrity. Appearing as often as she has in Katz’s pictures, Ada has become famous, the new perceptual Realist complement of Willem de Kooning’s Abstract Expressionist Marilyn Monroe and Andy Warhol’s Pop Jacqueline Kennedy.

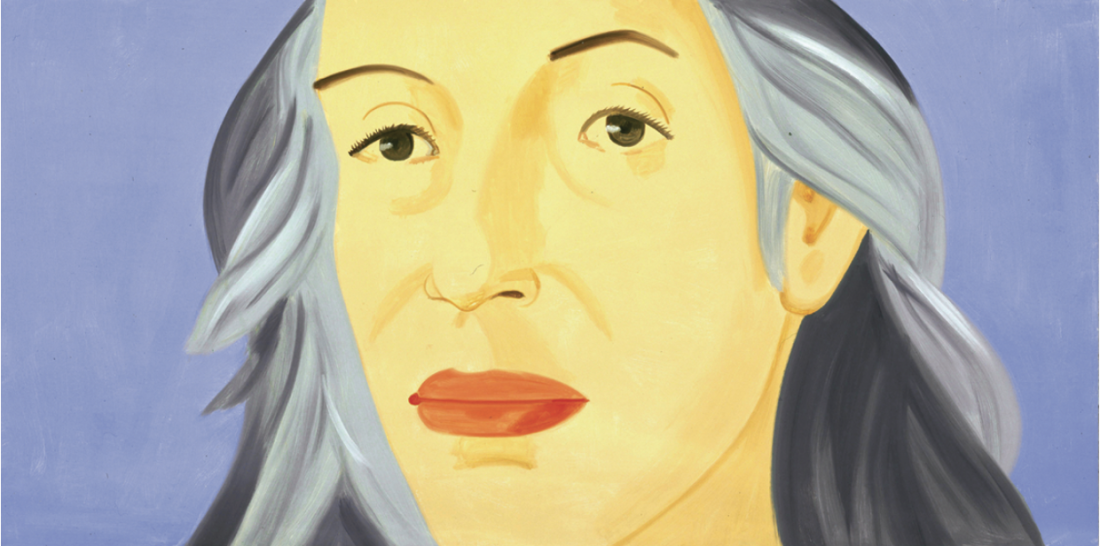

Alex Katz, Ada, 2005, oil on linen. Collection Galeria Javier Lopez Art.

Katz’s portraits of Ada are distinguished by their variety in composition and brush handling. He depicts her on canvas and in freestanding and relief cut-outs, in dissimilar settings from New York City to the Maine countryside, at different times of day and in diverse lights. Ada with Superb Lily, 1967, is suffused in dazzling sunlight. In contrast, the background in Ada’s Night is a field of jet black punctuated with tiny lit windows. Katz’s painting techniques encompass the nuanced gestural facture of Ada Ada, 1959, and the polished, hard-edged surfacing of Blue Hat, 2003. In Ada in Front of Black Pool, 1988, the silhouette of the back of Ada’s head in the foreground looks out on “Expressionistic” water, rocks, tree trunks and shore. Ten of Katz’s family and friends appear in John’s Loft, 1969, which consists of seven aluminium reliefs attached to the wall that make up a mural-size “picture.” In sum, Katz has greater scope in his painting than any other artist of his time. Yet, despite the diversity of his works, they all exhibit a strong sense of style—the Katzness of Katz, as Sanford Schwartz put it. In fact, his ability to move his painting in any number of directions while retaining his unmistakable style is one of his remarkable accomplishments.

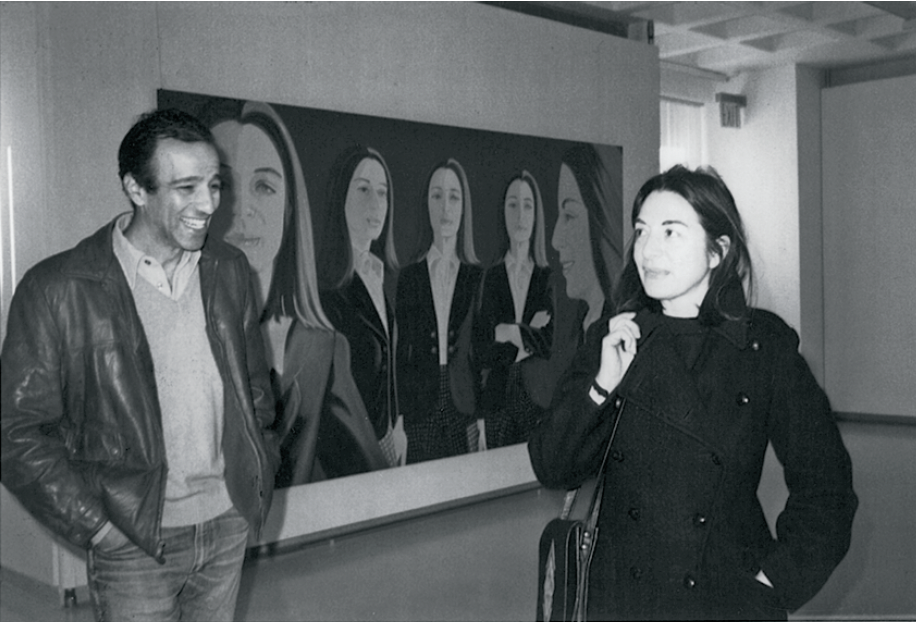

Alex and Ada Katz at Marlborough Gallery, 1973. Courtesy of Alex Katz.

Katz’s achievement is to have created an original and personal vision of reality and to have painted it beautifully, as the present exhibition of Ada’s portraits amply reveals. ■

“Alex Katz Paints Ada” is on exhibition at The Jewish Museum in New York from October 27, 2006, to March 18, 2007.

Irving Sandler is the author of a four-volume history of American Art and, most recently, the author of his memoir A Sweeper-Up After Artists,_ published by Thames and Hudson, 2003._