Aganetha Dyck’s Mad Hatting

Mid-morning outside a downtown warehouse. A sign skirting the top edge of six sand-blasted storeys reads in broken English: GAULT LIMITED WHOLESALE DRY GOODS. The tin sign is rusty and deceptive. Thanks to three years of inspired diplomacy, addled by the right mix of hard-nosed negotiation and the addition of $3 million, the Gault Building is the home of 22 cultural groups, eight studios (one a self-contained live-in), four galleries and a cinemateque. Called Artspace, the Gault Building has been transformed into the visual, literary, media and arts administration centre in the middle of Winnipeg’s rejuvenated core area.

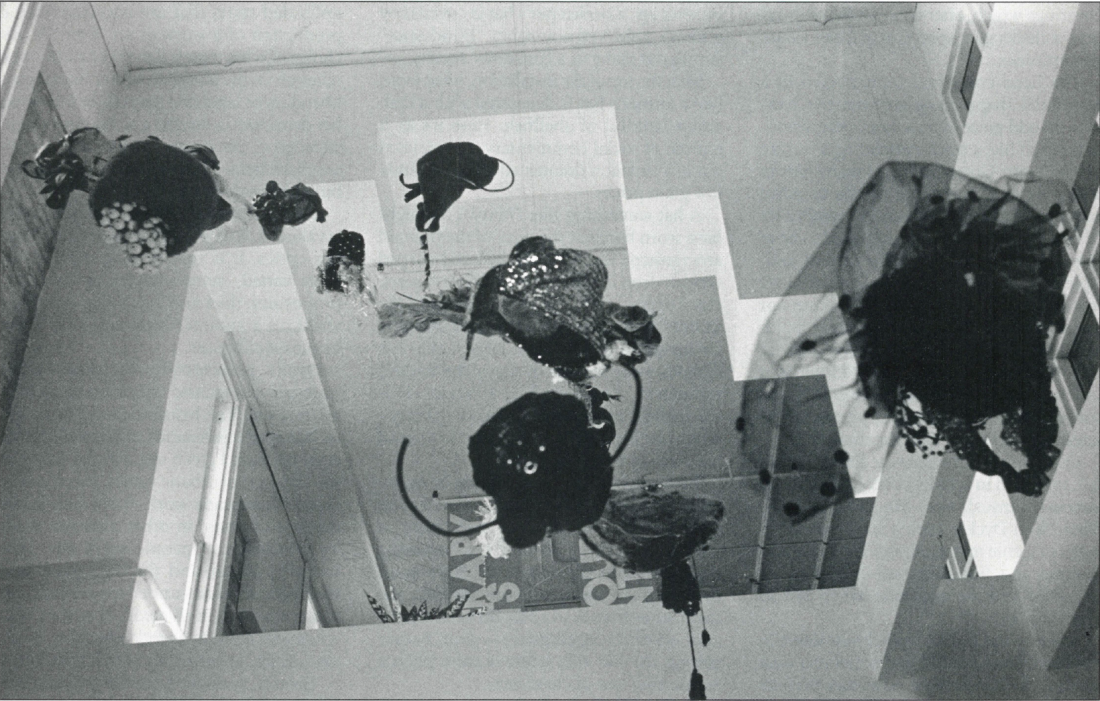

Something of the building’s new spirit becomes evident upon entering the lobby. Handouts, posters, banners and, most conspicuously, a permanent installation by Winnipeg artist Aganetha Dyck fill out this large open space. Dyck’s sculptural installation is composed of 42 handmade, found and altered head-coverings: a Mad Hatter’s inventory that seems to soar through the second-storey cutaway.

The lobby is north lit so the hats are illuminated evenly and democratically. In the breeze of circulating air, the trained and untrained eye can pick up a range of headcoverings which, after contemplation, suggests a challenging spectrum of ideas, values and attitudes.

The head-coverings are arranged in a pyramidal shape; most are women’s hats, with an odd piece of male head-gear insinuating itself like a novice attending a lecture by Germaine Greer. Seeing so many hats in a single place inevitably brings to mind popular phrases, like “so and so wears a lot of hats,” or “who are you supposed to be at this particular meeting?” The idea of multiple and ambiguous reference points isn’t lost on any of the painters, composers or playwrights who are obliged to change mindsets in order to balance their books or fill out their grant applications. Neither is it lost on the occasional philistine suffering through what may simply appear to be the latest concoction of experimental art.

Quite a few of the hats are handmade of felt, rendered in a variety of colours that are variously sensual, moss-like and emotional. There is in Dyck’s work a strong commitment to tactile materials, as if the process of making and perceiving art is something the artist and the audience has to feel its way through.

Some of the thickly veiled hats lower in the installation could blind you if you were wearing them; others are veiled hats through which you could see easily. There are sporty hats which are surprisingly thought-provoking and sporty hats which don’t provoke thought at all. Near the bottom of the installation, several hats contain what look like clusters of grapes. If wine occupies a central and symbolic position in thought process, then these hats are poised ready to despoil the floor.

Another work combines the protective face shield of an assembly-line worker with a Sunday “go-to-meetin’” hat that could as easily be found hovering above a blue rinse. This industrial/religious hybrid asks particularly pointed questions about what people believe; other pieces ask no less pointed questions about how society operates.

Installation, 1986, Artspace. Photography by Tom Fijal.

From the second storey, a stuffed pheasant looks down over the brim of a riding hat, an image of the victim taking a Pyrrhic free ride on top of its own worst enemy. It’s an arrangement that corresponds to a cynical interpretation of the social welfare system. Further up, a beekeeper’s hat is covered by a dense gold veil—another “blind spot” familiar to many in a consumer society.

Near the top of the installation, what looks like a farmer’s hat is decorated with a crab and a handful of shellfish. Here it’s as if a piece of social commentary materialized out of a situation dominated by consistently low grain prices.

A hat something like Henry VIII might have worn hangs at the apex of the pointed arrangement. Red and gold diamond-shaped orchids drop like fallout from this soft green cloud shape, while a tendril raps toward the underside looking for a foothold. Already an image of growth and decay, this hat embodies regeneration by way of the tendril’s movement. Because of its location—it is the highest and centrally placed—Henry’s would-be headgear coalesces the overall meaning of the installation.

Forty-two hats as a composition or meaning system represent a play between nature and the often cheap shot one-liners of culture. Perhaps I should say “meaning organism” rather than “system.” Since head-coverings are metaphors for intellect, the installation ascends to a play between natural and artificial intelligence—with nature getting the star role while culture plays a supporting cast of characters.

Yet for all its fresh air and optimism, Dyck’s installation is extremely contentious. Detractors overlook the natural resolution of the work, seeing instead a series of decorative signs. They find the installation short on tragedy, pathos, irony and humour.

One less than enamoured gallery visitor described the work as a “Lilliputian nightmare”—a range of affluently coloured headgear forever just out of reach. A female critic tagged the installation, cryptically, an “Ode to Nellie McClung”—viewing it as an historical, doctrinaire and one-dimensional work of feminist ideology. Those critics didn’t find in Dyck’s work the range and breadth of meaning possible—and desirable—in a piece of public art.

The critics’ problem extends itself to the way in which artists, writers and playwrights are being presented to the general community. A work which is merely a decorative exercise doesn’t square with the hard work, lobbying, number-crunching and failed or unfunded starts that are necessary in the production of a work of art. Even Dyck’s choice of what material to emphasize—she relies on tactile materials rather than metal, fiberglass or leather—plays right into what her detractors lament as a worn-out cultural stereotype. Once again, artists and writers are characterized as imaginative and mystical but rather soft-headed.

The controversy surrounding Dyck’s work is valuable. If anything can be learned from her critics, it is that making culture is a more varied, more complex and tougher proposition than anyone taking a leisurely stroll on a summer afternoon 100 years hence would guess.

Dyck’s predisposition towards tactile materials and archaic stylization admittedly omits a lot. The installation fits well into an historical rejuvenation of Winnipeg’s core area. It’s an old green space at the centre of the cheapest of urbane values. But as a conceptual landscape work, it operates at the expense of “hats” in other materials worn by thousands of people every day. Historically, labour and the disenfranchised have been seriously under-represented and misrepresented, in all media. It is ironic that it happens again in a work which extolls us, once again, to wear a lot of different hats.

There is, perhaps, a parallel problem and solution offered by the Artspace building itself. Finished stair-wells, air conditioning and awnings have yet to materialize. Like the building, the essential structure of Dyck’s work is sound. If the parallel holds, both the building and the installation can be seen as things in process rather than as finished products. That the completion of the installation and the building will require both a hard-headed and inspired approach to securing funds is an irony I hope will be less final than merely telling. ♦

Al Rushton is a video artist, writer and curator.