Adrian Williams

Paradoxically, the art opening, like a pefectly made b1ed concealing beneath its smoothed counterpane all the unseemliness of sloppy sex, delusions murder plots, private tendernesses, arguments and infidelities, actually closes off from view as much as it lays open. The gallery, with its clean lines, crisp white walls and gleaming floors, at first glance contextualizes each artist no matter how impoverished or successful, minimalist or baroque, fraudulent, meticulous or messy, in a setting that whitewashes everything into a pristine semblance of presentability. Once a canvas is hung, it is nearly impossible to see the hair-ripping torture it takes for an artist to squeeze himself into the frame. But Adrian Williams is an artist capable of keeping his mess present within the space of the gallery without the unfortunate contemporary tendencies to move into the terrain of cheap shock tactics and, thus, to say the least, knows what he is doing.

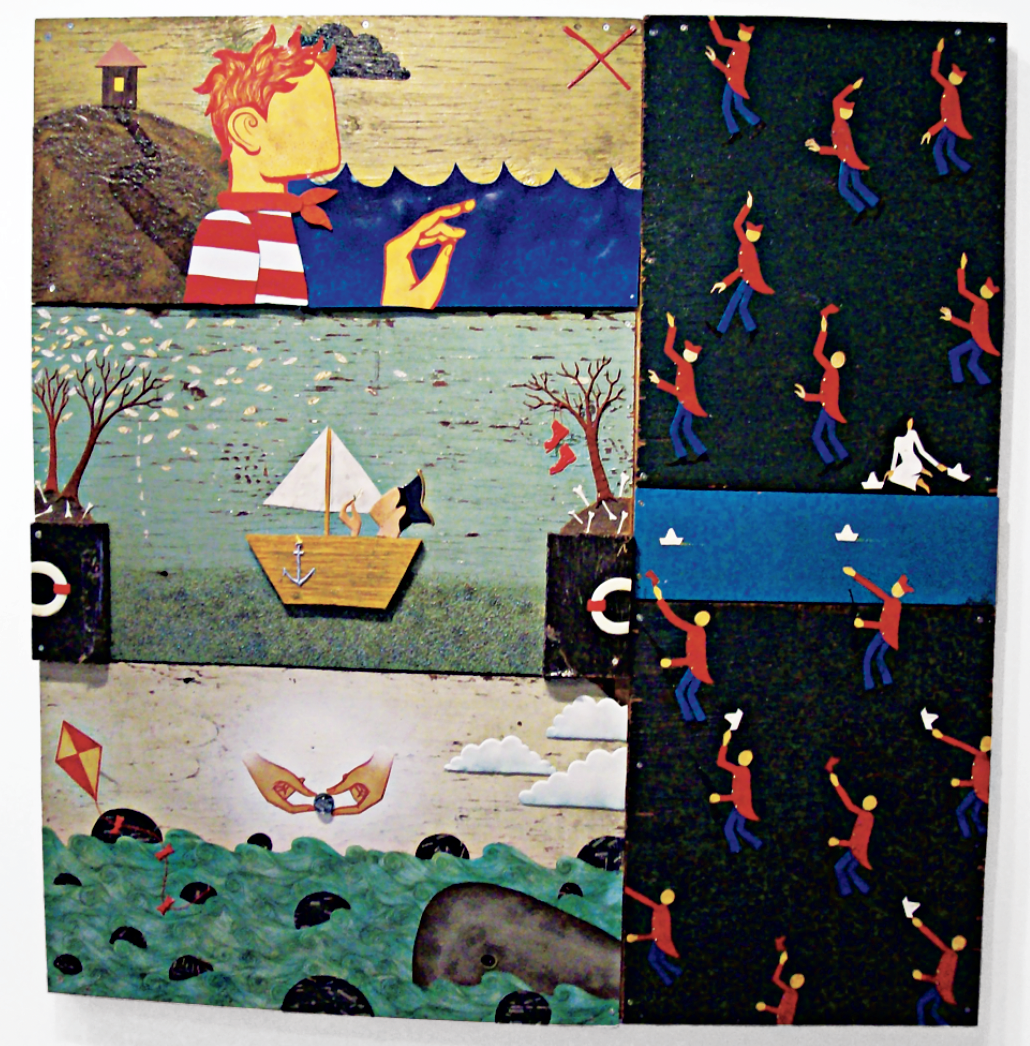

Adrian Williams, It’s Just Not There, Marco Polo, 2007, mixed media on found wood, 61 x 57”. Courtesy the artist.

To know what you’re doing in the cool, stultifying limitations of modernity is a challenging feat for an artist. Poetry, at one time the inexplicable and necessary component of any real piece of art is, at best, a concept, whereas irony—the best all-purpose cleaner money can buy—thrives. Irony has fumigated modern art, transforming it from that romantic, vigilant dictator of the soul it once was, into something esoteric; the viewer can access this kind of art with the mind (or with the aid of a curator), not with that dirty organ, the heart.

But Adrian Williams embraces this dirty organ in holding steadfast to his own sense of squalor and in excavating the beautiful filth of others in the form of a rotten piece of wood here, a mouldy book cover there. To use terrain already trodden on, or found objects as the raw material for work, is not a novel practice, which makes sense, since novelty would be the last thing Williams might consider when hammering, or gluing, or painting or drawing together one of his clairvoyant tapestries of human, really human, life.

Installation view of 12 book cover drawings, 2009. Courtesy the artist.

Williams muddles his panoramic glimpses into humanity—whether it’s lovemaking, love-losing, drunk fighting, or just plain failing—with the storytelling precision and humour of Bruegel and an awareness of beauty that would make Rousseau fall to his knees. That said, Williams’s tricky tendency to mute out facial features in his work seems uncharacteristically lacking in sentimentality and perhaps points to an inability to understand what he himself is creating. Or is Williams refusing to look at his bumbling characters straight in their hard-lined faces? Could a detailed face betray the sense of buoyancy that Williams maintains consistently within his work?

It is fair for an observer to question an artist’s purpose when noticing troubling patterns. Williams, in fact, would say it is actually quite human to do so. But if the observer’s charge is that Williams cops out by avoiding detail, the charge is completely invalid. In fact, Williams’s avoidance of faces is an intrepid leap into the essential. The stories he tells, often on found book covers, do not belong to him, nor do they belong to those long-haired ladies or confused gentlemen who appear on his pallets; they are part of the present, stories of the past and peeks into the future. Ownership is all but forbidden in Williams’s art; just as a monkey passerby might nab the hat from the hands of a sleeping young man, some other simian creature could mimic the lovemaking he watches through a lit window. As viewers we are as faceless as the monkeys, as blind as the drunken, and as tangled up in dreams as the men who somnambulantly saunter through Williams’s art in their pajamas and night hats. Our stories are their stories; their judgments are our judgments; our dirt is theirs.

Adrian Williams, Untitled, 2008, pen, ink, collage, polyurethane on book cover, 7 x 9”. Courtesy the artist.

There is nothing shut down or closed off on a Williams canvas; windows are perpetually open, people live among each other on the streets, artists burn up their work sending it into the zeitgeist before it’s complete, staircases come out of nowhere, and monkeys sit freely and openly on people’s backs. For Williams, a closed face is an open heart and an art opening is a place for him to lay his bare. ❚

“Travail/Work” was exhibited at La Maison des artistes visuels francophones in Winnipeg from January 29 to April 9, 2009.

Erin Hershberg is a Toronto-based writer whose work has been published in cinemascope magazine and the McGill Academic Journal of Culture and Cuisine.