Abdel Abdessemed

A black pall descended on the room in which “Conflict” was installed at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Its black chalk drawings of life-sized military figures toting firearms seemed to press in close on viewers, as though herding all into a position ripe for crossfire. This entailed a palpable sense of unease, which undermined the footing inside the room. As viewers moved from figure to figure, the impression of a sheer testosteronefuelled assault was overwhelming. The grunts were striding in pure, unfettered Leon Golub-like mercenary fashion, pupils dilated, fixated on their target(s)—and both the aggressive nature of their onslaught and the aggressive nature of their presentation were powerfully dovetailed.

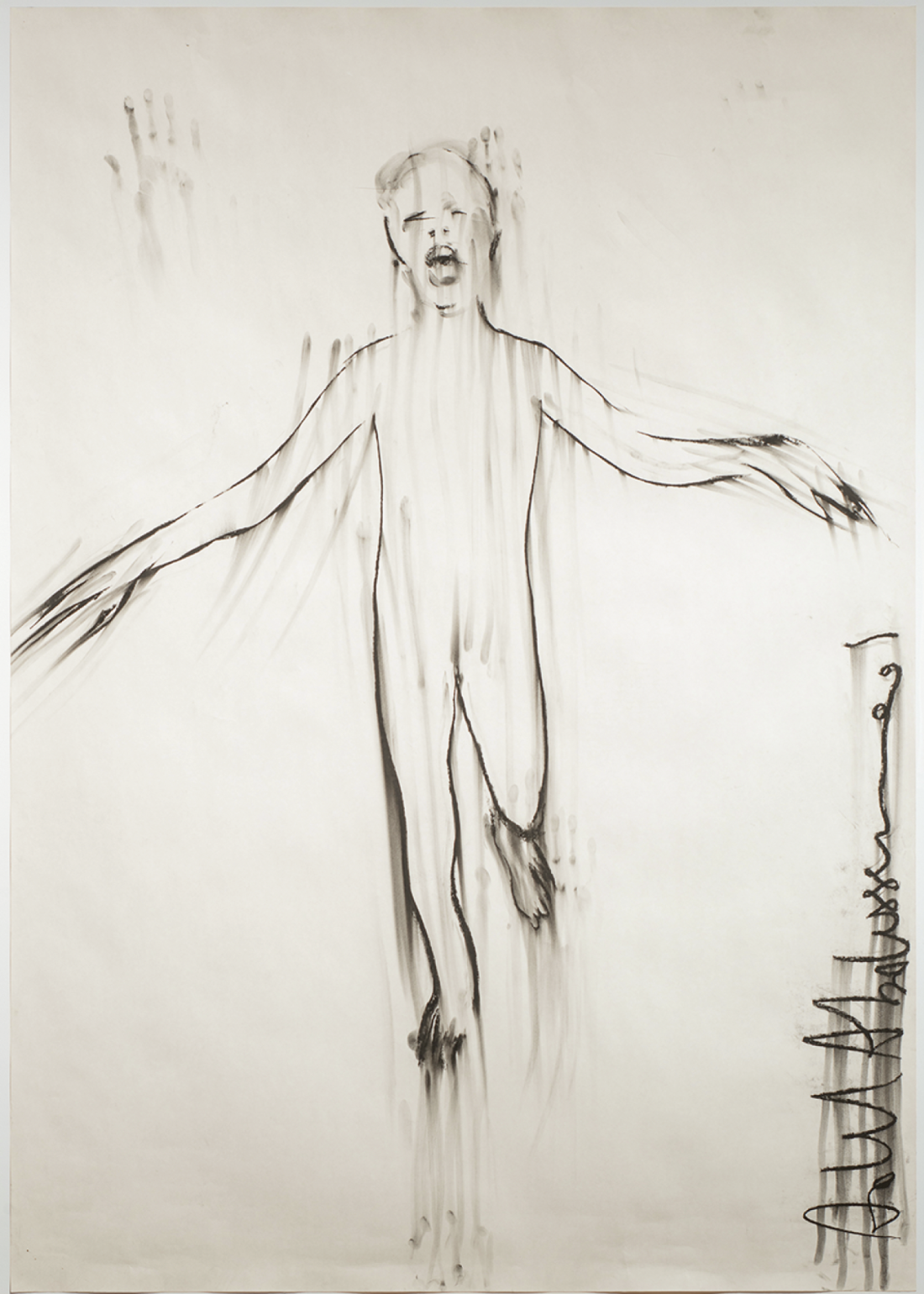

One of the drawings in the assembly was of a different subject; it was a harrowing rendition of a screaming nude female figure with her clothes torn off and her skin mostly burnt away. This drawing, Cri, 2007, was executed after Nick Ut’s famous Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph from the Vietnam War of the so-called Napalm Girl, and became its point of fulcrum and moral paradigm.

Adel Abdessemed, installation view, “Conflict,” 2017, The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. © Adel Abdessemed / SODRAC (2017). Photo: Denis Farley. Courtesy of the artist and Dvir Gallery, Tel Aviv – Brussels.

The subject, Phan Thi. Kim Phúc, was born April 2, 1963, and was immortalized in that photograph as an innocent victim of a South Vietnamese napalm attack. An inhabitant of the village of Trang Bang, South Vietnam, Kim Phúc joined other civilians who were fleeing from the Caodai Temple to the safety of South Vietnamese-held positions when a South Vietnamese Air Force pilot mistakenly identified the group as enemy combatants and attacked them. Ut’s photograph of a nine-year-old child severely burned on her back by liquid fire became one of the most haunting and enduring images of the Vietnam War. Napalm sticks to its victims like a jelly and burns up to ten minutes on the bare flesh. It was feared that her burns were so severe that survival was unlikely, and after an extended hospital stay and countless surgical procedures and skin grafts right up to the recent past, she is still in recovery. In 2015 Phúc, then 52, began a series of laser treatments that her doctor, Jill Waibel of the Miami Dermatology and Laser Institute, says will soothe and smooth the thick scar tissue that runs up her left hand and arm, up her neck and down her entire back. She is still with us, indomitable, an eloquent witness to the horrors of the war.

This installation interrogates violence with rare insight and moral force. The artist allies himself with the nine-year-old girl against all the powers of horror. The textbook definition of violence is the intentional use of physical force by human beings to inflict injuries on other human beings. Abdessemed’s concern here is less with a philosophical understanding of violence—say, with Slavoj Zizek or Paul Virilio as avatars—than with the mensurable effects of systemic violence on the living. It further applies to psychological violence as well: intimidation, humiliation, degradation, constituting, as it were, a further wholesale assault on the mind. This latter damage is particularly resonant today, given the extreme forms of torture inflicted more recently by Americans on Iraqi detainees in Abu Ghraib.

The institutionalized, systemic violence of the US military’s war in Vietnam—the napalm attacks by both aggressors and colluders, the now well-known butchery of the My Lai and other massacres—is brought back powerfully within the horizon of the present tense where it is a subject not of dead history but of continuing headlines writ large across the dark heart of Donald Trump’s America.

Cri, 2017, black chalk on paper, 184 x 130 cm. Private collection. Photo: The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Christine Guest. Courtesy of The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Abdessemed inscribes the mysterium tremendum, the nameless Other, across the horizon of his art. It is the Demon of Death (as analytical psychologist Edgar Herzog in Psyche and Death understood it) that carries us over the threshold here, cloaking the dead and eviscerating the living. The soldiers in “Conflict” are like reanimated human corpses themselves, hungry ghouls with horrifying masks and headgear resembling the wolf head Cap of Hades the Greeks spoke of, ritual shrouds that confer on their wearers a sort of invisibility as they wreak havoc and go about their deadly business. Killing emerges into the foreground here with the soldiers as tools and agents of annihilation.

It is in fact the suggestion of the act of killing that is used to confront and incarnate the tremendum, and to teach his viewers an incandescent moral lesson, drawing us emotionally into the sacral aspects of war, hunting and killing. “Conflict” summons up a proverbial Kingdom of the Dead, and raises inside our own heads old archetypes in the unconscious. The dark schemata of the soldiers’ faces reminds us that the representation in Indian temples of Shiva-Durgha was of a skeleton or stick figure wearing a dark cloak.

During a first look at the work there was the sense that Abdessemed was attempting to add “deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars,” in the words of Martin Luther King Junior, but the longer we spent there, the more we understood that spectacle or divertissement were not at issue, but that the artist was pivoting towards indictment and critique, and shining an unforgiving light on the relentless violence and dynamism of our time. He ushered the figures out of the shadows and named them like jackals, calling them out and down.

This exemplary exhibition is an integral part of the Year for Peace at the museum, an expansive program of activities and exhibitions launched in November 2016 following the inauguration of the Michal and Renata Hornstein Pavilion for Peace. Michal and Renata Hornstein were important museum patrons and Holocaust survivors who immigrated to Canada, just as Kim Phúc did. Kim Phúc, this remarkable and courageous survivor, now lives in Ontario and works as a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador. ❚

“Conflict” was exhibited at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from February 16 to May 7, 2017.

James D Campbell is a writer and curator in Montreal, and is a frequent contributor to Border Crossings.