A Review of Lunaris, Just About Us and Fragments from a Distant Past

This summer’s annual “Dance in Canada Conference” was marked by heated exchanges about how the dance community could best upgrade the visual literacy of its audiences. The major concern of the forum was the understanding of movement by the adolescent as spectator, performer and creator, particularly in the field of modern dance. The problem of how dance educators might effectively incorporate movement into the limited structure of physical education programmes received considerable attention, and a number of alternatives were proposed.

The Contemporary Dancers demonstrated this summer and fall that through a sense of community obligation, a number of imaginative and practical educational experiences can be created for a dance public. The Winnipeg School of Contemporary Dance Summer Session imported Fred Mathews to instruct in the Limon technique. Professional, intermediate and neophyte students from across Canada participated in sessions that explained this unique style of movement through demonstration and lectures on theory and historical development. The company also extended this opportunity to discover Limon in a Master Class at the “Dance in Canada Conference” effectively reaching a wider student assembly. Shifting from their roles as educators to performers for an audience consisting of professional dancers, choreographers, teachers and the general public, the company opened the second evening of “Dance in Canada Festival” with Anna Blewchamp’s Baggage. Whether one was on stage or seated in the audience, the five nights that the festival ran offered a constant and continuous exchange of ideas and choreographic styles.

Many delegates at the conference argued that contemporary Canadian choreography must demonstrate the influence of regional or national concepts of dance movement. Contemporary Dancers participated in this summer dance conference and afterwards the Company toured for almost three weeks, performing at “Jacob’s Pillow”, “Wolf Trap Farm International Children’s Festival”, and the “New York Dance Festival”. The company obviously assumes that movement can be an expression of the total world view of a group or individual and to limit experience to what is perhaps a youthful and transitory phase of Canadian Modern Dance is to deny the possibility that exciting modern and new dance will extend the range and achievement of the discipline. What may emerge is a community of inbred runts instead of balanced and informed dancers.

Rachel Browne and Suzanne Oliver in Just About Us. Choreographed by Rachel Browne.

After returning to Winnipeg Ms. Browne resumed her role as educator in offering a performance/demonstration afternoon at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. The programme consisted of descriptions of various movement techniques and a preview of their upcoming 1977/1978 repertoire. Apart from the advantage gained in educating the dance audience, I expect Ms. Browne and the Company members felt more confident in greeting an audience with works that had already been explained.

The programme in October opened with Lunaris, a work that choreographer Fred Mathews based on Limon. Six dancers in unisexual celestial blue leotards and cropped hair moved in harmonious design. The cool tones of their blue costumes become self-reflecting, almost magical, and against the background of a waxing moon these futuristic beings moved chromium crescent forms.

The Limon method advocates a confluence of breath and the natural force of the dancer’s internal motion. The result is that a choreographer will create infinite and highly individual executions of specific movements and definite technical difficulties for the six dancers. The problem was to allow the sum of their interpretations a coherent expression. The imagery of the moon’s phases was presented through a wonderfully unified progression that took the form of repetition and re-integration of motion. My interest built and shifted as the moon moved through its phases—from new to first quarter, from third quarter to full disc, each revolving continuously with the hidden dark of the moon. As the image approaches three quarters there is one noticeable inconsistency in this otherwise concise, elegant and fluid work. The music became resistant and conflicted with the general development of Lunaris to this point. Despite this minor lapse, the dance achieved its intended effect and never became tedious or diffuse.

It has been customary at the start of each new season for Rachel Browne to present one of her own works. The distinguishing characteristics of these pieces have included poetry, live and original music combined with the exploration of a specific period in the life of the contemporary woman. There was a bitter-sweet sense of loss and fulfillment depicted in The Woman I Am and especially Interiors. The earmarks were similar this year in Rachel Browne’s newest dance, Just About Us, created by the director for her teenage daughter. The musical score composed by Jim Donahue was approximately twelve minutes long and was scrupulously arranged and recorded on tape. Ms. Browne attempted to represent a conflict typical of a mother/daughter relationship through cyclical expressive repetition. The dance begins and ends with a woman on stage and the suggestion is that the student becomes the teacher in an orderly genesis. The roles of the two women are complex so that this instructive relationship is deliberately confused with a familial one. Mother and daughter exchange embraces to indicate their shared bondage and, if one is particularly observant, there is a moment of free ecstacy as the child breaks her ties. The interpretation of dance with music is particularly effective at this point as two voices float onto the black platform. Later as the dance wanes Marla Guberman’s voice progressively overcomes the dominant sounds of Donahue’s while on stage the initiate child becomes instructing adult.

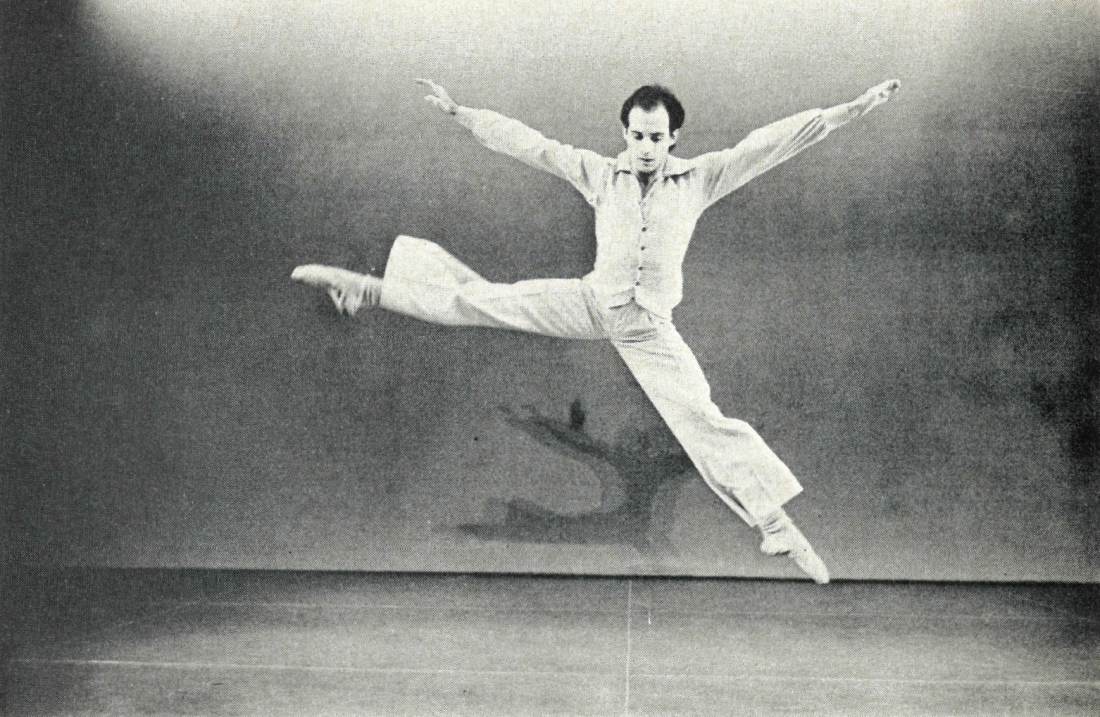

Kenneth Lipitz in Fragments From A Distant Past, choreographed by Norman Morrice.

The dance included a constant balletic pose and movement on the balls of the feet with upraised arms. There were additionally, a few brisk developpes, doglegged attitudes, chasses around the stage, and rather antique arm gestures. I sense that Ms. Browne did not really hear the music and was unable to blend the initial introspection required with valid modern dance expression. The danceable quality of the music demanded more than the choreographer offered.

Norman Morrice, artistic director of Britain’s Royal Ballet, set the third piece on the programme to Janaceks’ Second String Quartet and used it to thoroughly explore the love relationships in Janacek’s life. Fragments From a Distant Past intelligently employed the device of a memory within a memory to present the turbulence, passion and lyricism contained in the love experience. Occasionally to the detriment of the piece, the interpretation moved from figurative description to literal portrayal. At one point, as the women revolve around Janacek (danced by Ken Lipitz) they alternatively draw their knees towards their bodies and then extend their legs in splits. The gesture gave the impression that all three of the women were willing sexual partners. Whether Janacek was at the mercy of his own emotions or the whims of the three women was not made clear. What was implied was that he had merely to choose among the women which left more than one member of the audience reacting angrily to this seemingly chauvinistic view. Generally though, the dance was characterized by interesting interactions and clean, explicit movements. It should be considered one of the finer pieces in the company’s repertoire.

Rialto is familiar enough by now to Winnipeg audiences to be spared a lengthy review. Its inclusion at the end of the evening’s programme was a subtle inversion of dance history, not to mention a clever piece of stage craft. Gershwin’s music and the comic interpretations in the 30’s, choreographed by Rodney Griffin was a better ending to the performance than Lunaris would have been. But the range of expression that these two dances represent was an (unconscious?) testimony to the ability of the medium to give moving and evolutionary form to our most complex emotions.

Patricia Malone is a regular dance reviewer for Arts Manitoba. She studied both classical and modern ballet in Maryland before moving to Winnipeg.