“A Handful of Dust: From the Cosmic to the Domestic”

Of the duelling ideological strands running through modernism—proclamations of utopian progress twined with on-the-ground disaster—British curator David Campany attends to the latter, focusing on the 20th century’s repressed underside— decay, debris and death. The 326 photographs, documents and videos in Ryerson Image Centre’s (RIC) “A Handful of Dust” form thematic clusters that spiral out from a single enigmatic, now iconic, photograph—Man Ray’s Dust Breeding, 1920. The conversation engages a range of subgenres within art and documentary photography, including vernacular, forensic, abstraction and conceptualism. Each piece refers back to that one photographic event—the exhibition’s ground zero, its scene of disaster—contributing to a composite rendering of the long century (long, as all centuries seized by capitalism must be).

The exhibition’s value is registered in part by the venues that have hosted it, with RIC the sixth after its initial design for Le Bal, Paris, where Campany was invited to curate his “dream show.” A lifetime of viewing and thinking about photographic images is distilled into constellations of disparate yet interconnected images that build an alternate history of photography.

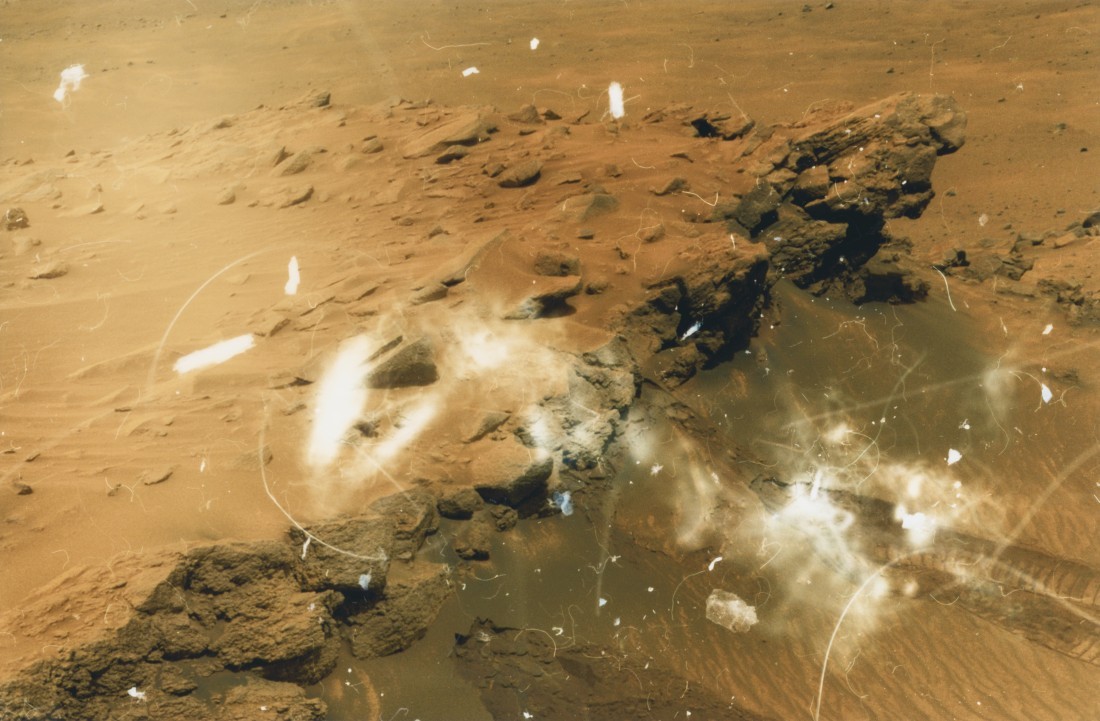

Eva Stenram, Per Pulverem Ad Astra (detail), 2007, chromogenic prints made from negatives exposed to dust. Courtesy of the artist; source images courtesy of NASA/ JPL-Caltech.

It is 1920. One mass-death war is done; the second, like a negative invisibly gathering its latent image, is in process. Marcel Duchamp’s sculpture The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (or The Large Glass), 1915–1923, lies still, in contrast to the bustle outside his New York City studio. For three months, like a long shutter opening, it collects the dust of history. It is a silent but productive dust farm. Prescient, Duchamp eschews vibrant modernist pigment and, instead, makes dust the medium of the century, but he maintains the painter’s process, removing some areas of the grey fluff, sealing others under varnish. His friend Man Ray records this “durational performance” through an actual photographic exposure. Campany, as detective, follows that image as it appears in surrealist journals and fashion magazines, and Duchamp’s The Green Box, and then traces its tenticular resonances through diverse themes, aesthetics, subjects and media—photography, abstraction, destruction and forensics, and in the conceptual and performance art that Duchamp helped spawn—all of which participate in the “return of the repressed” that Man Ray’s image seems to embody.

The ambiguity of Man Ray’s dusty image, with its uncertain subject and scale, opens associative channels to multiple formal and thematic realms: landscapes, abstraction, war and aerial views. Included are aerial photographs from both world wars, the first Gulf War, fracking maps and destroyed Roma encampments. A WWI aerial view printed from a cracked glass negative bears referential weight in its recall of Duchamp’s Large Glass, itself splintered in transit. Xavier Ribas’s expansive depictions of a Roma encampment in Barcelona destroyed by the property owner appears as a Google-style aerial of the region, a diptych of dust clouds and a grid of 33 large colour photographs showing the now uninhabitable fields of concrete rubble, Nomads (Part 1) and (Part 2), 2009. Three diptychs by Nick Waplington couple themes of war with abstraction: each of his three colour photographs showing Palestinians scavenging at garbage dumps built from refuse produced in illegal Israeli settlements is paired with an abstract painting using the same colour palette as the photograph (Adora, Kiryat Arba and Carmel, 2010). Sophie Ristelhueber’s À cause de l’élevage de poussière, 1991–2007, effectively bookends the show. The French artist photographed desert debris following the first Iraq War. Her enlarged black and white aerial photograph bears close resemblance to the exhibition’s first image, Dust Breeding, which served as reference for Ristelhueber throughout that project.

Eva Stenram’s distanced views introduce another of Campany’s linked themes: artists who, like Duchamp, use dust in their working process. Stenram made negatives from images of Mars sourced from NASA, then left them under her bed to gather dust. A series of 10 colour prints from those dusty negatives is presented here as a grid (Per Pulverem Ad Astra, 2007). Stenram embraced dust in her process, but most photographers consider dust a scourge to be obsessively kept from lenses and negatives. In each of Scott McFarland’s five large colour photographs, a male figure, wearing a differently coloured t-shirt in each, stands in front of a sandy shoreline, wiping his camera lens with his shirt. One imagines sand granules scraping across delicate lenses, marring photography’s promise to transparently represent reality. Bits of dust and hair, collected from McFarland’s studio, lie pressed between print and glass, presenting different levels of representation—the suggested lens dust and the real dust on the print (“Lens Cleaning” series, 2017). The dust that Stenram and McFarland incorporated in their photographs appeared by its own volition. Bruce Nauman produced art with another kind of common household dust: flour, made from grinding wheat for human consumption. In the video of his performance Flour Arrangements, 1967, Nauman pushes around a large mound of white flour into various configurations. Fine particulate— whether accumulated organically without human agency or as a result of our own destruction—seeps into and eventually covers all our environments, spaces, bodies, art and psyches.

The 20th century was a dusty one, with its bombs and human remains. Sparkles of radioactive dust coat lovers embracing in a clip from Alain Resnais’s film Hiroshima Mon Amour, 1959. Street photographer Jeff Mermelstein, while wandering New York streets after the World Trade Center collapse, captured, even as dust fell on his lens, a statue of a seated businessman within a littered landscape, coated with powdered concrete and ash (Statue, 2001). In a photograph from WWII three men casually peruse the intact bookshelves in the otherwise demolished and roofless Holland House library after an air attack. Another photograph shows the car that Mussolini travelled in when he was captured, then killed, by the Italian resistance, covered in dust in a storage garage.

Scott McFarland, Lens Cleaning Rodenstock Apo-Sironar 5.6/135 MM; James Perse Medallion Crewneck Jersey T-shirt, 2017, chromogenic print. Courtesy the artist, Monte Clark Gallery and Division Gallery. Images courtesy Ryerson Images Centre, Toronto.

In the 1930s the dust that buried swaths of the Midwest US was pictured on postcards and circulated for newly amassing audiences. The sizable collection presented here was acquired by Campany through the commercial open access archive eBay, a source described by him as the “dust heap of the twentieth century.” The curator-collector expressed a subversive enjoyment—in line with his chosen focus of the common substance of dust—in the interaction between such lowly vernacular photographs and the more venerated art pieces that shared the gallery walls. The photographs show desolate farmers on their desertified lands, trucks buried under hills of dust, a woman’s finger writing on a dustcoated desk, a child’s grave.

Two small prints helped to wrap up the exhibition with subtle humour, seeming to deny the dusty deathdrive evidenced elsewhere. The humble images conversed with the exhibition’s concluding image on the opposite wall—Ristelhueber’s more monumental Iraqi remake of Man Ray’s Dust Breeding: an anonymous trade photograph of a can of Dust-Off (1980), the essential darkroom accessory that labours for representational perfection, and a photograph of Marcel Duchamp’s gravestone bearing the words “Anyway, it’s always the others who die” (Bill Vazan, 1997). Together, they formed a triadic grouping that illustrated the exhibition’s thematic thrust— the simultaneous tragedy, banality, resistance and inevitability of dust and debris.

“A Handful of Dust: From the Cosmic to the Domestic,” curated by David Campany, was exhibited at the Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto, from January 22 to April 5, 2020.

Jill Glessing teaches art history at Ryerson and York universities, and writes on contemporary art and culture.