A Danceable Feast

Marcel Dzama’s involvement in the world of dance has been unpredictably layered. Even though he was raised in a city with one of the oldest classical ballet companies in North America (the Royal Winnipeg Ballet was founded in 1949) he never attended a performance in the 30 years he lived in the city. “I never went to ballet in Winnipeg because I came from a working class background and I was intimidated.” It wasn’t until he moved to New York in 2004 that he interested in dance. Surprisingly, that interest came about through a shift in his drawing. “In Winnipeg the drawings were more minimal, with only two characters, and when I came here they began to reflect my sense of claustrophobia. The drawings became very dense and chaotic and as a way of controlling the chaos I would put some of the figures in dance positions. I also used to draw animals a lot and they got turned into costumes and that slowly became a stage with a minimal background.”

New York City Ballet in Justin Peck’s The Most Incredible Thing. Photograph: Paul Kolnik. Courtesy New York City Ballet.

The evolution in his drawing made him an ideal choice to do the set and costume designs for the world premiere of the New York City Ballet’s production of The Most Incredible Thing. The ballet, choreographed by Justin Peck and with commissioned music by Bryce Dessner of the band The National, opened in February and will run throughout the company’s season until May 7th. The NYCB collaboration was not his first artistic engagement with dance. In 2008 he designed the costumes and developed the story in the music video for the Department of Eagles song “No One Does It Like You,” in which a marching army of men wearing long black stovepipe hats takes on a dancing army of women dressed in short tunics, kneelength stockings, and red Zapatista headpieces. The mutual annihilation of the two sides populates the heavens with a contingent of dancing ghosts. The women dancers conduct their war exercises en pointe. Dzama consistently turns ballet into his own genially macabre brand of martial art, in which competing armies perform the equivalent of a danceoff that leaves the stage littered with body parts.

In A Game of Chess, a 14-minute-long film made in 2012 with dancers from Guadalajara, he turned his admiration for Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, 1922, and Francis Picabia’s Relache, 1924, into another version of dance as struggle. This time the battle focuses on a lone ballerina who is forced to join a company of dancing chess pieces in a ballet involving stabbings, spurting blood, a decapitation, a Mexican assassination and finally, a rubble of dismembered chess pieces. A similar dark tale unravels in Une Danse Des Bouffons (A Jester’s Dance), Dzama’s 35-minute-long, black and white film made in 2013, which features Kim Gordon as Marcel Duchamp’s rescuer, saving him from a torture of arrows and an endless chess game. The film is a gambol of art references, from a David Cronenberg exploding head to a reprise of Erwin Blumenfeld’s prophetic 1937 photograph called Dictator. For Dzama, dance is a field of citations and his movement is always in the direction of homage.

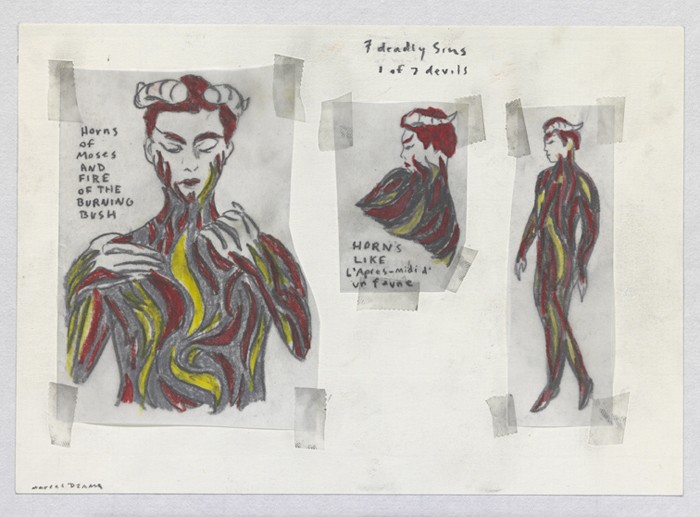

Marcel Dzama, costume sketches for The Most Incredible Thing. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

An element of struggle is the centre of The Most Incredible Thing as well. Taken from an 1870 dark fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, the story is about choosing between creation and destruction; the Creator makes a wondrous clock and the Destroyer sets about to break not only it, but also the people who admire it. Every hour, dancers representing different aspects of human history emerge from the clock in a marvelous display of ingenuity; among them a cuckoo bird, a trio of kings, the five senses, the seven deadly sins, and the Nine Muses. Adam and Eve also make an appearance in costumes that are a discreet arrangement of green leaves. In any paradise known to man, this Eve would set apples falling to the ground.

One of the most incredible things about the ballet is the sheer variety and number of costumes Dzama designed for it. He met with Peck and Dessner in October 2014 and by the time they met again in late November he had already done the drawings and designs for the 64 dancers in the ballet. But there is much more to his design than we see on stage. The New York City Ballet hosts an art series in which they ask a contemporary artist to install an exhibition in the promenade of the David H Koch Theater. This year, Dzama was the participating artist, which gave him an opportunity not only to develop a new piece, but to show the design process for the sets and costumes.

Marcel Dzama, costume sketches for The Most Incredible Thing. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

The process was elaborate. He envisioned the promenade as a large chessboard in which red and blue chess sets would dance to the end of things; he improved the Elie Nadelman sculptures at each end of the space by decorating them with his Picabiaed dots, and he set up display cases in which we can see unfolding the mechanics of invention through preliminary drawings, small terracotta figures and a series of stage set maquettes. The models are different interpretations of Alberto Giacometti’s 1932 surrealist sculpture called The Palace at 4 A.M. “I love that piece,” Dzama says. “Every time I go to MoMA I stare at it to see how it is made.” (Seeing how Dzama made his designs is part of the gift of this ballet. Everyone who attended the art series performances was given a charming 24-page takeaway called The Book of Ballet: La Chose la Plus Incroyable Dans Le Monde, co-published by NYCB and David Zwirner Books).

In addition to the making-of exhibition Dzama produced a video called The Tension on which History is Built, in which Amy Sedaris plays him as the director. In that role she manages to turn the characteristic bellicose ballet in an altogether positive direction; on two huge video screens at each end of the promenade you can see the red and the blue chess sets laying down their martial arms and engaging their aesthetic arms. The message of the video is that it’s better to make dance than war.