A Certain Kind of Animal Energy

Leon Golub Talks about Drawing

There are occasions in the life of an artist when they are obliged, whether through choice or circumstance, to reinvent themselves. Henri Matisse was a painter with whom Leon Golub had nothing in common, except a shared capacity to undergo a dramatic shift in the matter and making of their art. In the last 14 years of his life, bedridden and scissor-handed, Matisse clipped and collaged his way into a new pictorial expression with the cut-outs.

In the following interview, what Leon Golub called an “interesting little digression” was his recognition that “you only become self-conscious about your body when things start going wrong.” When things went wrong, he could no longer climb ladders and use a meat cleaver to scrape paint away from the surface of his mural-sized paintings. His reinvention was to focus on 8 x 10-inch drawings on paper and vellum using oil stick, ink and conté. “I’m trying to skim the surface,” he says, “get underneath the skin a little bit.”

Leon Golub, Exultant, 2003, oil stick and ink on vellum, 8 x 10 inches. © The Nancy Spero and Leon Golub Foundation for the Arts. All photographs courtesy the Estate of Leon Golub and Hauser & Wirth.

The drawing’s subjects were familiar—men and women of threatening mien and posture, and unsettling encounters with animals and our animal nature. But there was something new as well: a concentration on an edgy, performed erotics, and an imagination that was both satirical and satyrical. Leon pictured himself as a centaur, raucous and raunchy and unrepentant. The drawings he produced embody a familiar politics of resistance and a compressed, re-energized aesthetic. His fierce and feral self found a way to be equally empathic and reflective. He described what he was doing as “throwing drawings in all directions.”

The following interview was conducted by phone to the Golub/Spero studio in New York on January 30, 2004. It was done as research for essays that Leon had asked Meeka Walsh and myself to write for Don’t Tread on Me! Drawings from 1947–2004, the catalogue accompanying his exhibition that opened at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts in New York, before travelling to Griffin Contemporary in Santa Monica and Anthony Reynolds in London, UK.

Leon Golub was born on January 23, 1922, in Chicago, and in anticipation of the 100th anniversary of his birth, we are publishing this enlivening and enlightened interview. In it he addresses the art of drawing and the bodies, as he so eloquently puts it, who are “tensioned against the paper.” Leon Golub died on August 8, 2004, in New York.

Leon Golub, Club Satyr, 2003, oil stick and ink on vellum, 8 x 10 inches.

BORDER CROSSINGS: Have you always drawn?

LEON GOLUB: I drew as a child, of course, but we can jump ahead to art school. In those years in the late ’40s, I did a lot of drawing and some of it is quite imaginative and influenced all sorts of subsequent stuff.

Were you looking at other artists at the time?

Yes, but “primitive” art more than other artists. I used to look at publications like Minotaur and Cahiers d’Art. They were fabulous to look at.

Was drawing already an art form that had a discrete sense of identity rather than being ancillary to painting?

Yes. I don’t think I ever used it in relationship to the painting in those years. I can’t think of any drawing that connects to a specific painting. None. All the drawing was totally independent. There were two types. There was a certain number of figure drawings done in art school, and then there was quite a number done imaginatively. Subjects like birth or a whirlpool of heads, one or two dealing with lovers and a certain number dealing with skulls.

The skull has been with you for a long time and it turns up throughout the drawings.

We carry it with us, sir. It’s always there.

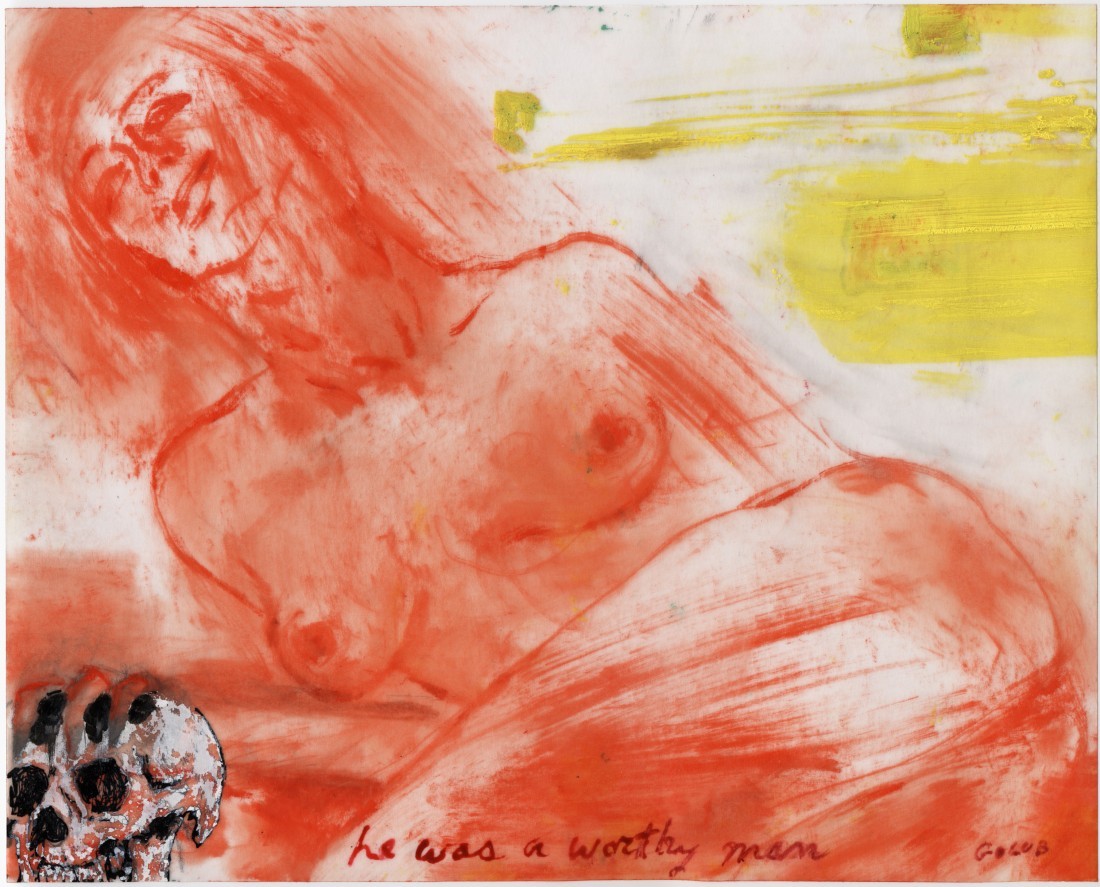

I’m thinking of the drawing He Was a Worthy Man (2003), which looks like a regendered and eroticized version of Hamlet’s Yorick.

Yes, it is a joke on that.

I’m interested in the range of the drawings with skulls. In He Was a Worthy Man, the woman’s memory seems almost post-coital. Whereas, if you look at a drawing like Trophy! (2002), the woman has a leering simian look on her face, which is a very different kind of contemplation.

Yes, a different kind of trophy. Actually, He Was a Worthy Man is post-coital. She’s lying there in this position and she’s thinking about her lover. He may have died five years ago, but every now and then she takes out her skull and thinks about him a little bit. She was fairly fond of him, you see.

That mixture of Eros and Thanatos is interesting.

That’s a good point. But Eros and the erotic have never been a major component of my work. I haven’t made women the component of my work. People have said to me they think there’s a lot of eroticism underneath it, but that’s totally speculative. Eros was there in a couple of things in the late ’40s and early ’50s, and I also remember drawing women almost like votive figures. Then in the ’60s, when I was doing the sanguine drawings based upon the “Gigantomachies,” there’s only a woman in one drawing, an older woman protecting a child. Incidentally, during the ’50s I did join on the subject of parturition. Then in the ’60s I did what was, if I may say so, a quite beautiful drawing of a female sphinx.

Why do you think you foregrounded Eros in the most recent drawings?

Monkey business. For one thing, it’s something I’ve never dealt much with, so it’s new territory. It’s a contrast to what I’ve been doing. Since the very late ’80s I’ve wanted to kick my art around a little bit. I wanted to be irregular, have curious things occur and so on. For example, the one that says “Time’s Up” (1997) has a little sign at the very top pointing upward. It’s a very little sign. It’s eschatological, if that’s the proper word.

Your work has been about eschatology from the get-go, if the meaning of the word encompasses the big themes of life, birth and death and the transitions between them.

That’s true and that’s one of the things that make me look very heavy to some people. “God, this guy is doing these lumpy figures. Who needs them?” In a way it set me aside from New York, which is both good and bad.

In the drawings you’re using slashes and gestures of colour that can be stage lights for an exotic dancer and at the same time can read as postpainterly abstractions.

They could. I am simply trying to jive up the drawings. Set up a counterpoint of some kind. If the female figure is prancing in some way, then you take a nice smear of yellow or purple and put it on the drawing.

Leon Golub, _He Was a Worthy Man, 2003, oil stick and ink on vellum, 8 x 10 inches.

Is that an instinctive gesture?

It’s a strange mix of calculation and spontaneity. It’s tricky because after I’ve finished a drawing, I sometimes decide it’s a little dull and so I liven it up. Even on a small scale, an oil stick in your hand is a mighty weapon. Then I liked putting in language. The language isn’t there from the beginning. The language is an added item.

The language, which often ends up being the title, indicates a way of reading the piece.

The most extreme example of that in the series is a drawing I called Exultation! (2002). Without that title, it looked like it was in the throes of despair or agony. By putting this other title down, the whole thing has a totally different air. You can do that with a lot of things. You can give a dark interpretation to Chardin, too, if you want.

You’ve always been interested in the relationship between power and drawing, and so I wonder what can drawing do in relation to that idea of power. What is drawing’s function?

That’s a very complex issue and every artist is going to handle it differently. Some don’t even think about it. They simply do the drawings from whatever position they occupy. I don’t really think of a crayon or pencil or something as a weapon, but I can think of the drawing as insidious or as going after something. There’s one drawing from 2002 that shows a rather husky, crude-looking figure. He looks like a brute and says, “I DO NOT BEND BENEATH THE YOKE.” The language is crucial to these pieces. I think they’re pretty nice drawings anyway and I like what they look like. They’re great fun to do on this scale and then to give them a twist. The title is either explanatory or, more often than not, it’s a twist. You throw a curve ball at your drawing and then the drawing responds in some way.

Is it a dialogue that happens inside the process of the drawing’s being made?

Sure. And it can be done at any stage. I very, very rarely start with the title. I may start with a sense of what I want, but I don’t go beyond that. And then at the final stage, I look around and think, well, how do I give it a kick? It’s like starting a motor. The language is like a motor, and that’s pretty exciting for me at that level. I have all kinds of phrases that I use and I keep writing them down. They’re always around.

You’ve also said you’re interested in what you call “irritable tensions.” Another phrase you used in 1982 is “moments of raunchy restlessness.” Are these drawings still about raunchy restlessness and irritable tensions?

That really is a tough question. Things get smoothed out in time. Even Goya can get smoothed out to some degree. But you don’t smooth him out altogether and he’s still raw as hell. I want my drawing to retain an edge, okay? I don’t want somebody to come and say, “Oh, my God, look at those violet tones.” I want somebody to say, “Why does that violet interrupt that figure in that way?”

Leon Golub, The Wounded Satyr, 2004, oil stick and ink on Bristol, 8 x 10 inches.